Art Articles

1. Anthony Gormley

2. 15 Second Films

3. Mystery Pigment

4. Aviary

5. Charles Saatchi

6. David Hockney

7. Wealth of Damien Hirst

8. Comic Books

9. Jeff Koons and Popeye

10. Popeye and Copyright

11. More On Damien Hirst

12. Women In Art

13. Invisible Art

14. Video Before YouTube

15. Andy Warhol and Food

16. Art Theft

17. Abstract Art and The Mind

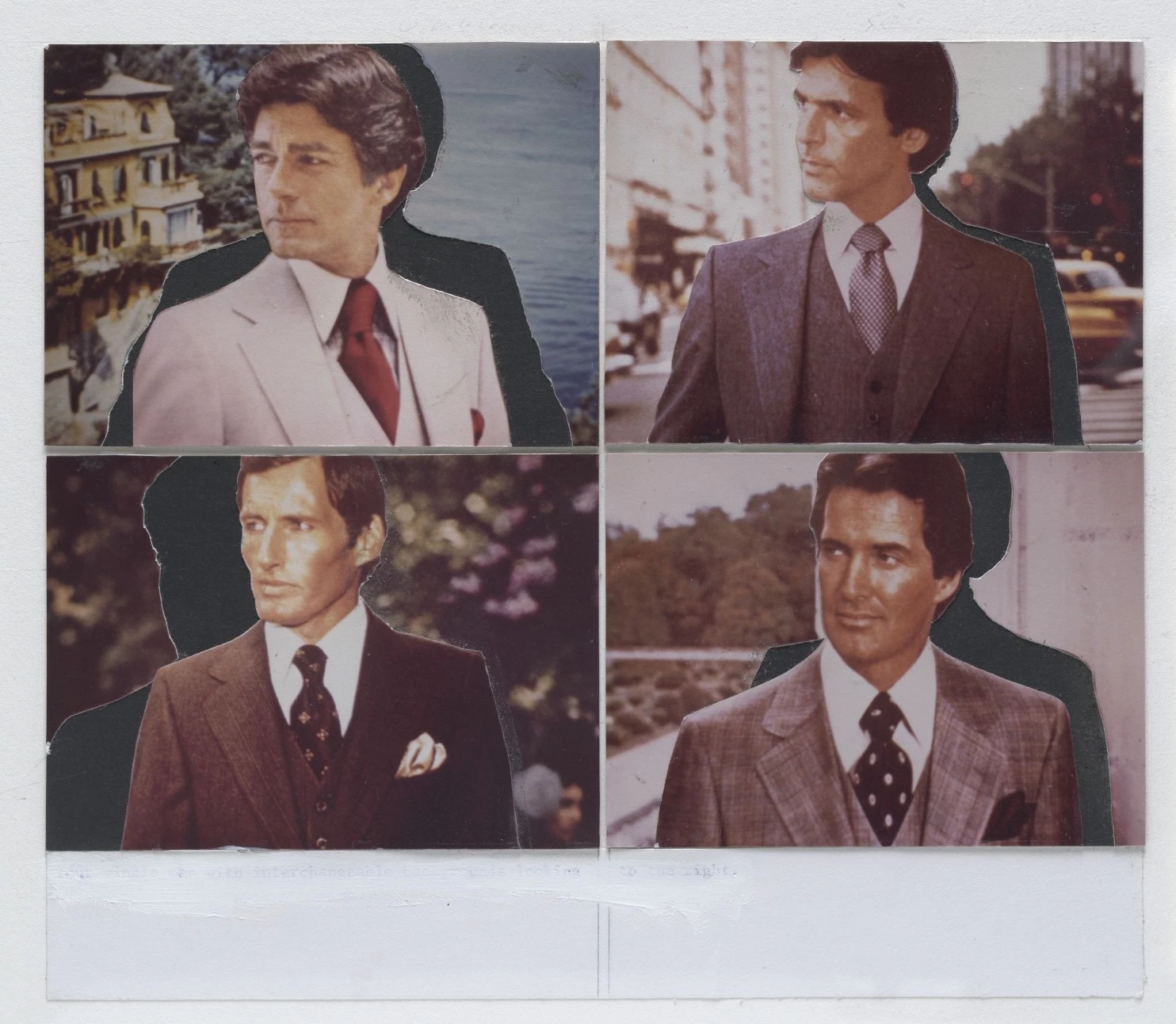

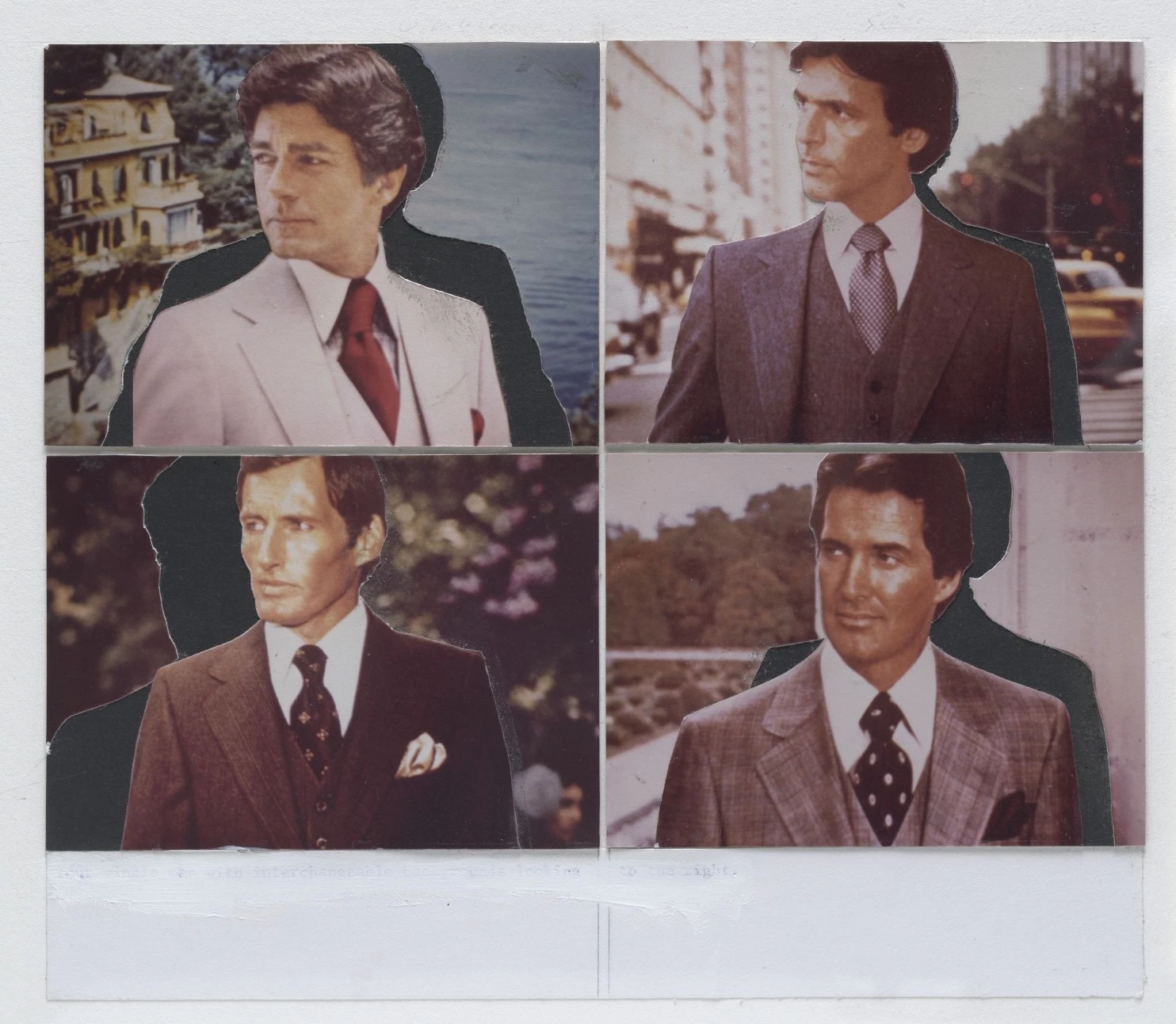

18. Authentic Movie Stars

19. Seth Godin on Art

20. Jack Vettriano

21. How to create instant 3D animations

22. Banksy - Art Outside The Frame

23. Grayson Perry on Art

24. Creative Advertising

25. Fakes

26. Comic Book Museum

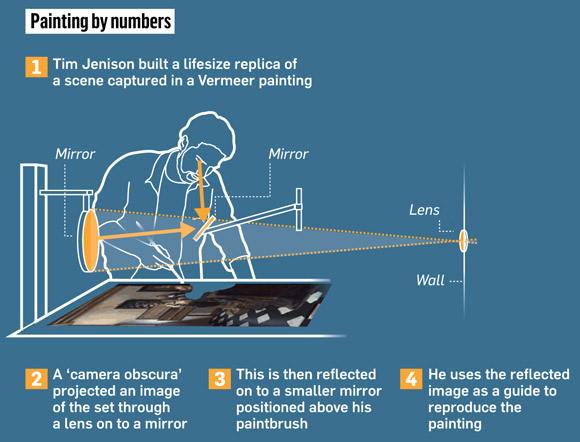

27. Vermeer's Camera

28. Wartime Loot

29. Wolfgang Beltracchi

30. The Critic (A.A.Gill)

31. Close Copies

32. The Art of Perfume

33. The Forger They Couldn't Prosecute

34. A Future For Movies

35. What Makes It A Masterpiece?

36. Digital Art

37. Constable vs Turner

38. Slow TV

39. Investment

40. Luxembourg

41. Artist Royalties On Resale

42. Richard Prince and Copying Art

43. Managing Collectors

44. Banksy's Dismaland

45. Problems of Living In A Comic Book Superhero World

46. Copying Art - The Bean and the Bubble

47. Pop culture

48. Alexander Calder

49. Prince Charles

50. Outsourced Art

51. Paint It Black

52. The Art UK Project

53. The Bust of Queen Nefertiti

54. The Secret Life of the Real Banksy, Robin Gunningham

55. Guerilla Drama and Music

56. Painted By Computer

57. Damien Hirst and Copyright

58. Secret Knowledge Part 2

59. LA The Liquid Shard

60. Roy Lichtenstein's Sources

61. Guardian Long Read on Art Forgery

62. AI art

63. Paul Gauguin

Anthony Gormley

-

In a dusty room a young woman wearing a protective mask is filing down Antony Gormley's buttocks. The Gormley she is working on is one of dozens that are piled rather disturbingly throughout the vast studio, like casualties in an android war. Some are curled, foetus-like, others with arms spread like a crucifix, a few have limbs contorted at unfeasible angles. Near by a man is welding together tessellated panels that will form one giant abstract metal Gormley.

Then in comes Gormley himself to oversee his latest production line of clones. The buttock-filer is rubbing down the very newest model, made two days earlier when the artist went through the routine he has done some thousand times in the past 30 years. Naked but for a covering of clingfilm - to stop the plaster ripping out his pubic hair - he lays down to be bandaged and covered in goo until several hours later he is sawn free.

Do you ever get fed up with his naked body, I ask the woman. She laughs and before she can answer Gormley says: It's not sexual, you know. In fact, he insists it is a form of meditation - he's a Buddhist, so should know - although to me it resembles a rather extreme spa treatment. It is the only time, he says, when I'm not expected to do anything.

And now the army of Gormleys - the 100 who line up looking out to sea in Crosby, Liverpool, in Another Place, and perched along the Thames skyline in Event Horizon, whose gargantuan big brother, with added wings, forms the Angel of the North - are set for world domination. Already in New York, 31 Gormleys have been positioned around Madison Square Park, whose conservancy commissioned the project: the figures are meant to be seen from the park, the cast iron men at ground level and fibreglass Gormleys high up on skyscrapers, including on the Gridiron Building and on the 25th floor of the Empire State itself.

Gormley has long wanted to bring a large public art work to New York, the city that, he says, kept him alive during his years of penury, raising his three children (two boys and a girl, now adults, by his wife, the painter Vicken Parsons) and working in Peckham, South London. My first collectors were all from there. New York singlehandedly kept me going for ten years. In the 1980s a gallery here was the only one I had in the whole world. I think it is an amazing place. It could be rarefied and snooty. But it is intensely practical, about getting on and doing stuff. You always feel you are plugging into some huge force of energy.

Officially opening on March 26, Event Horizon, New York, has already stirred the city. As in London, the naked Gormleys have been mistaken by worried citizens for would-be suicides, forcing the NYPD to issue a statement calling for calm. And several commentators have remarked that it is in poor taste, since a body exposed at height has tragic associations after 9/11.

Gormley disdains any comparison: But they were all falling, weren't they. It was all about desperation and having nowhere else to go, he says. This asks the big question: what it is to be a human animal. Once you displace a body, all sorts of questions naturally follow. I've no idea what will happen. I just hope that people will be stopped in their tracks and look again at where they are and maybe themselves and maybe at the world around them.

As he approaches his 60th birthday, Gormley is more prolific than ever. A major installation, Flare II, a mighty steel and wire sculpture, is in situ in St Pauls Cathedral. He has collaborated with the choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui on two ballets, Sutraand Babel, designing sets that are more than background furniture but intrinsic to the works, which play at Sadlers Wells this year. Meanwhile he is completing the book chronicling One and Other, the art sensation of last summer in which members of the public were given an hour each atop the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square.

Gormley's studio is in the desolate badlands behind Kings Cross, but when the gate swishes open, it reveals a bright white modernist building in which some of the 20 young artists who work with him bask in a sun trap. A model of Angel of the North, which has come in to be repaired, stands in the courtyard.

Ask Gormley a question and he will pontificate in careful, modulated sentences filled with abstractions until you are forced to interject. This inclination, plus his height and upper-class accent - his father was a rich businessman who first marketed penicillin - gives him a patrician bearing. Yet, with his long ears, large nose and tendency to peer at you curiously through his spectacles, he reminds me of Roald Dahl's BFG.

The body that he has replicated so often is well-made, with a solid muscle mass around the shoulders rare for his age. You wonder if a portly, pigeon-chested artist would ever have created these works. When I remark that he's in good shape, his eyes flash with delight. Well, that is very, very kind of you, but I'm not particularly proud of my body, he says disingenuously.

Does he work out? I go swimming three times a week and Julian comes and we do wondrous exercises. A personal trainer? He's a dancer. I do stretching and pilates type things on the floor. I like to think maybe that is self-delusion that all I am interested in is maintaining a degree of proprioceptive body-consciousness. I would like to feel that I am aware and in touch, fully present physically.

Though since he is forced to examine younger versions of his body, a bit thinner, less low hanging, he is unusually aware of ageing. I am f***ing old, he says plaintively about his impending 60th birthday and notes that he has staff already working upon his archive just in case he drops dead tomorrow.

Undoubtedly what he will be most remembered for is celebrating the heroism of Everyman: whether naked and vulnerable against the cityscape or atop a lonely plinth, the human figure stands stoic and timeless. I don't know about heroic, he demurs. I like the idea that everyone has a story to tell, that each of us is contributing to a made world for others. Every person is one pixel in a bigger picture.

As with the London Event Horizon, which inspired Facebook campaigns to have the Gormleys kept up on London rooftops for posterity, it has been suggested that One and Other should be an annual event. Yes, it quickly became one of those summer things, like Henley or Ascot, Gormley says. A bit of potty Englishness. But, God, it was hard enough to organise once . . .

He is rumoured to have been disappointed with some of the lamer plinth people, but this he denies. I feel unable to criticise. They made it their own. I had no expectations. We needed in a way those who were happy to sit up there with their cup of Earl Grey tea and collapsible garden chair and ring Mum. It was an exercise in our freedoms and a nicer way than the Bulger case for Britain to take stock of itself. Usually it's some awful social services disaster that causes people to think, who are we?

Gormley applied to the plinth lottery for a place, but didn't win. He'd planned to take up a bag of clay or to make a structure with sticks: something Blue Peter-ish.

Success came to Gormley relatively late: he did not win the Turner Prize until he was 44. That he is not hugely wealthy like YBAs such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst, a generation younger, doesn't bother him. Growing up in a wealthy, if strict Roman Catholic family, with chauffeurs and a grand London house, immunised him against materialism. I'm aware, he says, that I don't need very much. But it has helped him to leave Peckham for a home in Camden and paid for his mighty studio, purpose-built by the celebrated architect David Chipperfield, in which he has been able to increase and diversify his output.

Neither is he dismayed by critics who are disdainful of his popularity, calling him repetitive and shallow. For me the big question is where art fits in people's lives. Is it a place that people go to know and to extend themselves? Or is it a pursuit of the few? Art critics are more concerned with the making of art.

When I ask if he can imagine a time when he won't cast his own body, he sighs and says he looks forward to that day. But it never happens because I can't think of another way. I wish I could think of a better way of making the work. But to me it is going back to the basic condition, which is: I am here now, I am an animal living in time, dependent on air, food and having a place. For me this is the first principle.

To Gormley the body is not only the place we inhabit, but the source of all knowledge about the Universe. I think that my final interest is the abstract body, which is a recognition that we don't own our own bodies. They are part of a system that we barely understand. The atoms in our body come from chemical reactions that happened in galactic activity at the beginning of space-time. And it's very extraordinary that consciousness is part of the mix.

The body is the closest that we come to the realisation that we don't control anything.

15 Second Films

-

While obscure auteurs such as Isabel Coixet and Brillante Mendoza are feted and fawned over, a British film-maker whose work has been seen by over a million people in the last fortnight is wandering the Cannes Film Festival with no entourage, no publicity team and nowhere to sleep.

Peter Johnston wants to alert the world to what he believes is the antidote to the bloated, self-indulgent arthouse movie: the 15 second film.

He has commissioned or made 62 of these nano-films for his online gallery, The 15 Second Film Festival.

To qualify films must be 15 seconds in length, with ten seconds for opening and closing credits. Typically each takes two weeks of leisurely preparation, about half a day to film and three days to edit - rather less than the four years it took to make Up, the festival's opening night film.

Prevailing trends are against him. Half the films gunning for the Palme d'Or this year are more than two hours long. The early favourite, A Prophet, is an epic two-and-a-half hour French prison drama.

Critics are grumbling about the running time for Quentin Tarantino's new offering Inglorious Basterds: you could fit 592 of Mr Johnston's mini-films into its 2 hours and 28 minutes.

But Mr Johnston, 43, is undaunted. 15 second film is an art form in itself, not a stepping stone to making longer movies, he said. It's like a filmic haiku or a three panel cartoon strip.

All the same creative cogs are engaged as when you make a full length film. You have to think about the sound design, the timing and economy of shot.

We've made documentaries, comedies and two spaghetti westerns.

Not all of them are successful but film-makers love it because it's so immediate.

Mr Johnston's films are not showing at the Cannes festival but he has been invited to exhibit at others, including Robert Redford's Sundance Festival. Roddy Doyle, the writer, has completed a film for him and he claims that Neil Jordan, the director of The Crying Game and Wayne Coyne, the frontman of the band The Flaming Lips have both agreed to have a go. Now he is hunting for Tarantino.

Mr Johnston, from Belfast, came to Cannes with nowhere to sleep and just 200 euros, roughly the price of one night in a cheap room in the centre of town.

A large man with a broad red face beneath a shock of grey curls, mirror-lensed Aviator shades and a handlebar moustache, he sports a tweed jacket with a cigar tucked in the top pocket and carries a large inflatable pig and a battered suitcase. The pig is supposed to be an attention-grabbing swine flu joke. The suitcase is his office and his luggage. It contains hair spray, a pair of fresh sports socks, a stack of demo DVDs and a camera.

He is extremely serious about his vision. He sees the future of the cinema screened in bite-sized snatches on iPhones, Blackberries and eReaders.

What I'm doing with the 15 second film project is the birth and rebirth of cinema, he said. All the innovation now is coming in short films where you have complete artistic freedom. The kids on You Tube are accidentally evolving a new cinematic language.

His latest effort, iSnort has become a hit on YouTube, with more than 1.2 million hits in the last week. It shows him snorting three lines of cocaine off his mobile phone. The white powder is really a 15 second animation on the phone's screen.

It is a gimmick but he also sees it as proof of the appeal of his medium.

I'm an action artist and a film maker. What did Warhol say? Art is what you can get away with.

Mystery Pigment

-

ScienceDaily (May 18, 2010) A team of researchers from the University of Barcelona (UB) has discovered remains of Egyptian blue in a Romanesque altarpiece in the church of Sant Pere de Terrassa (Barcelona). This blue pigment was used from the days of ancient Egypt until the end of the Roman Empire, but was not made after this time. So how could it turn up in a 12th Century church?

Egyptian blue or Pompeian blue was a pigment frequently used by the ancient Egyptians and Romans to decorate objects and murals. Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 AD), this pigment fell out of use and was no longer made. But a team of Catalan scientists has now found it in the altarpiece of the 12th Century Romanesque church of Sant Pere de Terrassa (Barcelona). The results of this research have just been published in the journal Archaeometry.

"We carried out a systematic study of the pigments used in the altarpiece during restoration work on the church, and we could show that most of them were fairly local and 'poor' -- earth, whites from lime, blacks from smoke -- and we were completely unprepared for Egyptian blue to turn up," Mario Vendrell, co-author of the study and a geologist from the UB's Grup Patrimoni research group, said.

The researcher says the preliminary chemical and microscopic study made them suspect that the samples taken were of Egyptian blue. To confirm their suspicions, they analysed them at the Daresbury SRS Laboratory in the United Kingdom, where they used X-ray diffraction techniques with synchrotron radiation. It will be possible to carry out these tests in Spain once the ALBA Synchrotron Light Facility at Cerdanyola del Valles (Barcelona) comes into operation.

"The results show without any shadow of a doubt that the pigment is Egyptian blue," says Vendrell, who says it could not be any other kind of blue pigment used in Romanesque murals, such as azurite, lapis lazuli or aerinite, "which in any case came from far-off lands and were difficult to get hold of for a frontier economy, as the Kingdom Aragon was between the 11th and 15th Centuries."

A possible solution to the mystery

The geologist also says there is no evidence that people in Medieval times had knowledge of how to manufacture this pigment, which is made of copper silicate and calcium: "In fact it has never been found in any mural from the era."

"The most likely hypothesis is that the builders of the church happened upon a 'ball' of Egyptian blue from the Roman period and decided to use it in the paintings on the stone altarpiece," Vendrell explains.

The set of monuments made up by the churches of Sant Pere, Sant Miquel and Santa Maria de Terrassa are built upon ancient Iberian and Roman settlements, and the much-prized blue pigment could have remained hidden underground for many centuries. "But only a little of it, because this substance couldn't be replaced -- once the ball was all used up the blue was gone," concludes Vendrell.

Aviary

-

By reducing development costs and making new features possible, cloud computing promises to create opportunities for software developers. A New York-based startup called Aviary is hoping to cash in on that promise by offering graphics programs that compete with far more expensive software.

Aviary's software allows anybody with a Web browser to draw illustrations or edit photographs. Founded in 2007, Aviary uses Adobe's Flex, a general-purpose platform for developing Internet-based applications, to make software that lets people modify photos, create illustrations, and share the results. Aviary's applications run in Flash, through the Web browser on a user's computer. Images are saved to the company's private servers rather to a local disk drive--the conventional way of storing files. The private servers are continuously backed up to Amazon's S3, a service that provides bulk online storage. If Aviary's servers become overwhelmed because of, say, a glut of users, the system stays afloat by transferring files from S3 to users instead.

Aviary's software development process has been the work of just a dozen or so programmers, and it has afforded a quick return on their effort. Because they can update the software as often as they like without requiring users to install patches or upgrades, a working version of an application can be rolled out the door as soon as it's complete, with refinements made later. Matt Wenger, president and CEO of the software company GroupSystems, says that cloud applications can be cheaper to develop than other types of applications, especially because it removes the need to worry about how and where users install software. "You write one version of the application and you install it in your own controlled environment [on your servers]," he says, "and any changes are tested and rolled out in that environment. The net of it is that you spend hundreds of hours less in support over the life of a product for a group of customers."

But while cloud computing can make product development and marketing more efficient, it has its own quirks. For example, Aviary needed a way to save huge image files quickly across a network. "An artist's work flow generally requires frequent saving," says Avi Muchnik, Aviary's founder. "This means that we'd theoretically need the capability to send huge files multiple times in the span of a few minutes." But constantly sending large image files back and forth over the Internet would strain Aviary's servers and frustrate users with slow connections. The company's solution is to detect incremental changes and transfer only those small pieces of the file that have changed.

Cloud computing provides more than just convenient storage. When artists allow people to use and modify their work through other media-sharing websites, the result can be a free-for-all. But Aviary tracks changes in images, so there is a record of how the work has been used. Artists can even levy royalties, which Aviary's software enforces automatically. If a person creates an image and assigns it a royalty of 50 cents, and another artist incorporates it into a composite work and wants to sell it, the second artist would have to sell the composite image for at least 50 cents, with that money going back to the original creator. This easy royalty-sharing scheme creates a business model for artists that would have been impossible without cloud computing.

Aviary's software offers fewer features than Adobe's Photoshop and Illustrator, the gold standard among graphic designers and artists. But converts like Shawn Rider, manager of technology solutions at PBS, say they like it because they can access files from any Internet-connected computer and collaborate easily with other users, all for a very low price. Aviary offers access to a free version of its software with basic design tools. For $9.99 a month, users get more features as well as access to the royalty-sharing system.

Aviary also provides an application programming interface (API), which allows other businesses to integrate its image-editing tools into their websites. The New Yorker has used the tools for a cartoon contest, and the New York Daily News recently held a photo-editing contest to alter the image of Air Force One's embarrassing flyover of New York City in April.

As for the future, Aviary is looking beyond image editing. In March, the startup acquired Digimix, a small company that makes Web software for audio editing; it may also start developing software for inexpensive online video editing, which should have a ready market among the hordes of YouTube contributors.

Charles Saatchi

-

Charles Saatchi has been one of the most influential forces of the contemporary art scene. Founder of global advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi, and the most influential art collector of our time, he has vigorously shaped the contemporary art scene while contradictorily remaining an elusive, even reclusive figure.

Though he famously refuses to be interviewed, you can now read his brutally frank responses to a battery of questions put to him by leading journalists and critics as well as members of the public. If you have a question you would like to ask Charles Saatchi please email editorial@thedailybeast.com. This is the first in a continuing series of new questions and answers from Saatchi. Check back soon for the next installment.

In your estimation, how much of the last decade's art explosion is due to the fact that the art market functions as an unregulated stock-market? (As in, no rules re: insider trading, gaming the system, pumping & dumping...)

When you say insider trading, do you mean museum board members getting early notice of artists about to be given wide exposure in a touring high profile exhibition, and laying down a few works in advance? And do you also mean people who buy an artists' work in bulk, and then put up one of their works in a major auction, and quietly bid up the price, to raise the value of all their others?

All very cynical I'm sure. But the only people who get hurt are other speculators, who overpay, and end up with a lot of artwork of a transitory value that is unsustainable. My view is that anything that is done to promote art and artists, everything that broadens the number of collectors and visitors to museums, and increases the visibility and interest in contemporary art - that's fine and dandy. Some people in the art world bemoan the hedge fund millionaires spending freely to acquire ostentatious displays of wealth and coolth for their giddily chic designer duplexes. Others bemoan art being treated as a commodity.

But most of the bemoaning is because the art world is stuffed full of bemoaners, bemoaning about everything.

Art collectors were spivvy and profiteering even during the Renaissance.

You shall not covet your neighbour's wife, nor his car.Do you believe in the 10 Commandments?

An overrated lifestyle guide, unsustainable and largely ineffective, only succeeding in making people confused and guilty. For example: You shall not covet your neighbor's wife, nor his house, nor his servant, nor his ox, nor his donkey, nor anything that is your neighbor's. This was always obviously a no-hoper of a Commandment. Coveting is all everyone does, all the time, everyday. It's what drives the world economy, pushes people to make a go of their lives, so that they can afford the Executive model of their Ford Mondeo to park next to their neighbor's Standard model.

And would you want to be married to someone who nobody coveted?

What is mankind's greatest unsolved mystery that particularily puzzles you?

Why kamikaze pilots wore helmets.

Why do you hang clothes on a washing line and not on a drying line?

Why does a fat chance and a slim chance mean the same thing?

Why is it called a TV set when you only get one?

What would you call a burger made of ham?

If man evolved from monkeys and apes why do we still have monkeys and apes?

How can you hear yourself think?

Is there art on other planets?

When I first encountered Minimal Art in New York in the late 1960's, Sol Lewitt's conceptual structures, Carl Andre's metal floor plates, Donald Judd's galvanized steel boxes, I remember having the romantic notion that this is what art would look like on a highly advanced distant galaxy.

The work appeared so far removed from all previous earthly art, it was easy to fantasize about cerebral Venusians floating ethereally above a work by Judd, and enjoying its rigorous beauty much as we would admire a Michelangelo.

Do you read your reviews, and take it personally if they're negative? I have an idiosyncratic relationship with reviews. If they're approving, I fear that the exhibition must be pedestrian. If they're disobliging, I feel for the critic, who is clearly unenlightened about contemporary art, insecure about a lack of visual perceptiveness, a crabby soul, for whom it would be a kindness to cut short a morose, sour life.

A perfectly balanced perspective, as you can see.

David Hockney

-

"Come in quick, before he gets out," says David Hockney, opening the door of his Kensington studio while restraining a biggish dog. Hockney is in London for the opening of a show called Drawing in a Printing Machine, which charts his latest co-opting of high technology. Only three days earlier, I had seen him feted with an hour of speeches at what was described on the invitation as the solemn opening of a show of his landscapes, Nur Natur (Just Nature), in the exquisitely unspoilt little medieval town of Schwabisch Hall, in southern Germany. He was looking relaxed and fit, having previously spent some time in his favourite spa, Baden-Baden, with his partner, John Fitzherbert.

In that itinerary, you can begin to grasp the many sides of the 71-year-old artist's current life. It seems a good idea, therefore, to start by asking him where he now lives primarily - Los Angeles, London or Bridlington, in Yorkshire? Lots of people still think you live mainly in Los Angeles, David, I hazard. Because I don't make announcements, he replies, with his usual drollness.

It was as though I had suggested some sort of Times Court Circular should be available. When people ask me where I live, I always say I live wherever I happen to be, he adds.

In any case, he continues, I was never away from Yorkshire very long. My family was there, so I was always going back. What I realise now is that Bridlington is a sheltered place; London is not a sheltered place for me. There are loads of people wanting my time, which I am not willing to give now. So Bridlington is a perfect place, a little isolated town. The nearest big town, Beverley, is 20-odd miles away; York is 35 miles. It is quite physically isolated, which I like about it. He's not cut off from the LA side of his operation, however, as he is quick to point out. Of course, nobody is electronically isolated now. My sister, Margaret, has a computer, and it was she who turned me on to one of its uses. I do sketches. She would say, if I came in at about six o'clock, What did you do today?, and so I would show her the sketchbook and she would scan it onto this computer. Then we realised we could send it to [Hockney's assistant] Gregory in California. Six o'clock in Bridlington is 10am in LA. So I would send him two or three drawings. Suddenly there is a connection, a very direct connection. Everything, including paintings, goes back to LA because it's my actual physical base. That is where all the archive material is. I can't move it. There's a hell of a lot of stuff there.

Bridlington, where he now has a big studio, is perfect for him at his age, he says. Every day, I work. And when I stop work, I am still thinking about it.

It's there he has found the trees that dominate his oil paintings now. In the Just Nature exhibition in Germany, the large, naturalistic paintings magically transport visitors straight into the Yorkshire woods. Hockney found the local German landscape a little bit like East Yorkshire... not too many people, very small roads without white lines in them, little rolling hills and individual trees that you could see. In one room, you can look at some sketchbooks in showcases, and on the wall his sketchbooks are flicked through for you on video.

Much of Hockney's early work was urban, and full of ideas and different styles. I wondered whether the Yorkshire landscape was making him a realist painter who is ruled by nature. He has talked of freestanding trees being the best physical manifestation we see of the life force.

But he stresses the continuity of his inspiration as an artist. If you have lived in Los Angeles for 25 years, you do know the power of nature there.

People here might call it La-La land and stuff like that, but I will point out that they are very aware of the power of nature, simply because the earth can tremble. They have earthquakes. They never forget that nature is a very powerful force. I read in a paper that after earthquakes in LA, most of the damage to people has been from broken windows and people treading on glass with bare feet. So I always have slippers by the bed there.

And, as you know, I have a rather lovely garden in LA. It has taken 20 to 25 years to get to what it is. I am surrounded by nature. LA isn't the concrete city a lot of people think. It is actually full of green, with a lot of wild animals. I could not let my little dogs out at night, because there are coyotes out there.

It seems a long way from coyotes to Drawing in a Printing Machine, his show at the Annely Juda gallery, although it does contain landscapes as well as portraits. The prints are made by drawing and collage, then printed out on inkjet colour printers, Hockney explains in the catalogue. They exist either in the computer or on a piece of paper; they were made for printing, and so will be printed. They are not photographic reproductions. The strongly coloured portraits feature many of the usual suspects among Hockney's family, friends and assistants, but also less familiar faces: his Yorkshire neighbour Sir Tatton Sykes, for example, and Francis Russell, a Christie's expert. The strong colours are echoed in the landscapes - in a piece entitled Summer Sky, swirling skies over fields so vivid that they seem to be in motion; in Rainy Night on Bridlington Promenade, shimmering puddles of cerulean blue where you can almost hear the raindrops plopping down.

Hockney is quick to ridicule the misconception that this work was some sort of computer art, in which the computer rather than the artist dominates. Most people thought they knew what computer art looked like, but of course that is like saying they know what brush art looks like. It is daft. What did Leonardo use to paint the Mona Lisa? Well, he used brushes; so if I get a brush I can do that, can't I? No! A brush, like a computer, is merely a tool.

For a variety of reasons the art world, together with the media, is sharpening its focus on Hockney. A recent headline in a London evening newspaper jokingly dubbed him iPriest of Art, thanks to his current passion for using an Apple iPhone to make little coloured drawings, which he may then send to a friend.

Furthermore, an auction record is expected next Wednesday for an iconic painting that belongs to Hockney's famous series of Los Angeles masterpieces. Beverly Hills Housewife (1966-67) is estimated to fetch between $7m and $10m at Christie's New York. It immortalises Hockney's great friend Betty Freeman, a discriminating patron of the arts, who is captured standing near the pool outside her immaculate modern house, in a long purplish dress.

One aspect of LA he probably doesn't miss, however, is the smoke-free lifestyle imposed on him there. He's had similar problems in a Liverpool taxi, where he counted six separate signs telling him not to light up - he had been to a concert there, and the vehemence of his attack on the local powers-that-be for producing so many antismoking notices almost threatened to revive the Wars of the Roses. It's a freedom issue for him. How Hockney hates bossiness and the nanny state. I've never forgotten the time when he said that Tony Blair reminded him of a school prefect.

Hockney greatly values the right to be in charge of his own life, and he remains sceptical about saving the planet by not using plastic bags. We are puny little creatures scratching around on earth, he muses philosophically. Some humans are less puny than others, however, and when you think of Hockney's unstoppable creativity over the past 50 years - not to mention the generosity of his gift last year to the nation, via the Tate, of the magnificent 40ft-wide picture Bigger Trees Near Warter, 2007 - he increasingly seems nothing less than a giant among artists.

Wealth of Damien Hirst

-

There are artists who follow their muse and starve in a garret en route.

That wouldn't be 43-year-old Hirst, though. Once an enfant terrible, he is the most powerful person in the contemporary art world, according to the magazine ArtReview. His position is the result of original and distinctive art (which famously includes animal carcasses in formaldehyde) and, of course, the money he makes.

Hirst is now so well known, he can sell straight from the auction house rather than through galleries, which traditionally demand 50% commission. A two-day auction at Sotheby's last September, entitled Beautiful Inside My Head Forever, featured 223 lots and fetched £111m - a record for a sale dominated by one artist. His success came while stock markets plummeted and investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy.

Hirst said at the time: "A lot of people believe artists should be poor, that you're not a real artist unless you are covered in paint with holes in your jeans. I think I have helped change that perception, me and Andy Warhol and Picasso and all the guys who took the commercial aspects on board."

Hirst certainly isn't scared of investing in the brand. He ploughed £15m into his For the Love of God project in 2006: a platinum cast of a human skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds. The skull, thought to have belonged to a 35-year-old European man who lived between 1720 and 1810, was bought by a group of anonymous investors the following year for £50m.

Hirst has a vast studio and £3m country pile in Gloucestershire. He also owns studio and exhibition space in Lambeth and Peckham in London.

While there is little money in his main firm, Murderme, which made £719,000 profit on £1m-plus sales in 2006-07, his wealth is substantial. Indeed, his manager now believes he is worth a billion dollars. We take a more cautious view, however, putting Hirst at £235m this year, allowing for tax and the recent collapse in the value of modern art.

Comic Books

-

We are continually reminded that we are living in a convergence culture, with meetings between old and new media creating new possibilities.

It would appear that an early example of this was the emergence of comics in the late 19th century, with the old worlds of art and literature meeting through the development in printing processes and the technology of mass publication. In truth the appearance of comics was a re-convergence, because in the early days of communication art and writing were one, with symbols, icons and pictographs telling complex stories about myths, laws and religion.

Comic stories often draw on the mythological apparatus of the hero, the lawgiver and the god to retell ancient stories. The emerging field of comic studies explores the power and potential of this form of communication.

From the comics that children read, to adventure stories aimed at older readers, to erotic comics and art comics, this intersection of words and pictures is generating an enormous amount of critical commentary, shown by the increasing number of comics modules offered at universities.

This comes at a time when, after centuries of distrust of images as seductive and easy and the veneration of the Word as the gateway of knowledge, Western culture find itself becoming more and more dominated by images.

Those who conclude that culture must be 'dumbing down' rarely consider that the images dominating our attention are more highly coded that ever, and more laden with meanings. There's nothing simple about images, and the simplest of them generates a sea of words. It is no surprise then that comics, once regarded as trash culture, now attract attention from academics. And just as Pop Artists drew on comics, today we find writers such as Jodi Picoult and Ian Rankin embracing the medium.

Jeff Koons and Popeye

-

Popeye by Koons has contemporary relevance because the character was conceived during the Depression

Depending on whom you ask, Jeff Koons is either one of the most brilliant artists alive or one of the most irritating. Either way, he has been among the most influential figures in the art world for three decades. But the facts cannot be denied: he is record-breakingly expensive at auction, an inspiration to Damien Hirst, the subject of important solo exhibitions in Europe and America and a particular hero in France, where he was made a Chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur in 2007.

All of which makes it something of a surprise that there has never been a show dedicated to his work at a British public gallery until now.

The Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park has announced details of an exhibition focusing on Koons's Popeye series. It opens in July and is pitched partly as a cultural comment on the economic crisis because the spinach-guzzling cartoon character was conceived during the Depression.

Julia Peyton-Jones, the director of the gallery, said: It does seem absolutely extraordinary that an artist of Jeff Koons's distinction should not have had a show in a public space in the UK before. Hans Ulrich Obrist, her co-director of exhibitions, said: This show is incredibly urgent. But it would have been urgent 10 or 20 years ago. There have been Jeff Koons shows all over Europe and the United States but not in England.

Like Andy Warhol before him and Hirst a decade later, Koons cultivated a distinctive public persona. Early on, he hired an an image consultant and placed adverts in glossy art magazines with photographs of him surrounded by the trappings of success.

In 1991 he unveiled Made in Heaven, a series of paintings and glass sculptures depicting him in explicit sexual poses with his then wife Ilona Staller. Ms Staller, better known as La Cicciolina, was a porn star who was elected to the Italian parliament in 1987. They split up in 1992, leading to a vicious custody battle over their son Ludwig.

Since then Koons has made a giant puppy out of flowers to stand guard outside the Guggenheim in Bilbao and, most recently, announced that he is working on the world's most expensive artwork.

Train will be a working reproduction of a steam train (it will make its own steam and move its wheels), hanging from a 161ft (49 metre) sculpture of a crane. The estimated cost to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will be $25 million

None of these works will be at the Serpentine, which will concentrate on the Popeye series, begun in 2002. Familiar Koons formats will be represented, such as his cast reproductions of children's inflatables and collages made with images from popular culture and snippets of bare female flesh.

The work explores his characteristic themes of consumerism, taste, art history, mundanity, childhood and sexuality and like most of his output, it will be almost all be made by his team of assistants rather than by him.

A former Wall Street banker from Pennsylvania, Koons made his name in the early 1980s when he presented vacuum cleaners in neon-lit glass cabinets and basketballs floating in salt water to an entranced Manhattan art world

The art factory

Jeff Koons set up in SoHo, New York, and hired more than 30 staff to make his increasingly kitsch output.

Early conceptual pieces included Rabbit, an inflatable bunny rendered in stainless steel.

His series, Banality, culminated in 1988 with Michael Jackson and Bubbles, a life-size, gold leaf-plated statue of the singer and his pet chimp. It sold for $5.6 million.

Popeye and Copyright

-

I yam what I yam, declared Popeye. And just what that is is likely to become less clear as the copyright expires on the character who generates about £1.5 billion in annual sales.

From January 1, the iconic sailor falls into the public domain in Britain under an EU law that restricts the rights of authors to 70 years after their death. Elzie Segar, the Illinois artist who created Popeye, his love interest Olive Oyl and nemesis Bluto, died in 1938.

The Popeye industry stretches from books, toys and action figures to computer games, a fast-food chain and the inevitable canned spinach.

The copyright expiry means that, from Thursday, anyone can print and sell Popeye posters, T-shirts and even create new comic strips, without the need for authorisation or to make royalty payments.

Popeye became a Depression-era hero soon after he first appeared in the 1929 comic strip, Thimble Theatre. Segar drew Popeye as a working-class Joe who suffered torment from Bluto - sometimes known as Brutus - until he can't stands it no more. Wolfing down spinach turned Popeye into a pumped-up everyman hero, making the case for good over evil.

Popeye the Sailor made his screen debut in 1933. According to a poll of cinema managers, he was more popular than Mickey Mouse by the end of the Thirties.

During wartime, the Popeye tattoo was etched on thousands of soldiers and sailors, who aligned themselves with his good-hearted belligerence.

The question of whether any enterprising food company can now attach Popeye's famous face to their spinach cans will have to be tested in court.

While the copyright is about to expire inside the EU, the character is protected in the US until 2024. US law protects a work for 95 years after its initial copyright.

The Popeye trademark, a separate entity to Segar's authorial copyright, is owned by King Features, a subsidiary of the Hearst Corporation - the US entertainment giant - which is expected to protect its brand aggressively.

Mark Owen, an intellectual property specialist at the law firm Harbottle & Lewis, said: The Segar drawings are out of copyright, so anyone could put those on T-shirts, posters and cards and create a thriving business. If you sold a Popeye toy or Popeye spinach can, you could be infringing the trademark.

Mr Owen added: Popeye is one of the first of the famous 20th-century cartoon characters to fall out of copyright. Betty Boop and ultimately Mickey Mouse will follow.

Segar's premature death, aged 43, means that Popeye is an early test case for cartoon characters. The earliest Mickey Mouse cartoons will not fall into the US public domain until at least 2023 after the Disney corporation successfully lobbied Congress for a copyright extension.

Sailor and spinach

— Popeye was added to the Thimble Theatre Olive Oyl strip in January 1929

— Elzie Segar was told to tone down Popeye's aggression as it was a bad influence on children

— Though it is a myth that he was coopted to promote spinach by the US Government, spinach sales in America rose by a third in the decade after his appearance. A tie-in Popeye Spinach brand is one of the most popular in the US

— Popeye was the first cartoon character commemorated by a statue, in 1937 in Crystal City, Texas, the self-proclaimed Spinach Capital of the World

— Popeye animations, cartoon strips and merchandising generated $150 million a year by the 1970s

— The Popeye's Chicken & Biscuits chain was named after Popeye Doyle from The French Connection film. It now endorses the cartoon character

— The burger-loving J. Wellington Wimpy character gave his name to the Wimpy restaurant chain

More On Damien Hirst

-

On the eve of Tate Modern's retrospective, the economist Don Thompson argues that the artist has changed the art market for ever.

Damien Hirst, at 46, is the richest artist the world has known. Estimates of his wealth range from £215 million up - way up. Certainly, he is worth more than Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and Salvador Dali combined at the same age, and those three are at the top of any list of artists who measured success in monetary terms. Hirst is the art world's 1 per cent, or perhaps the 0.001 per cent. Next month Tate Modern will recognise his work with the longest-running retrospective it has ever offered a living artist.

Whatever you think of the fact that Hirst's work is made by a production line of technicians, or his impact on the direction of contemporary art, many identify him as the most important contemporary artist of the past 20 years. His skills as a marketer of conceptual art are legendary and have eclipsed his skills as an artist. Many of the important developments in how contemporary art is perceived, or how it can be marketed, have come from Damien Hirst.

Among the works at Tate Modern are some of Hirst's most significant pieces, those on which he made his reputation in the early 1990s. A Thousand Years (1990), in which flies and maggots are hatched inside a vitrine and migrate over a glass partition towards a cow's rotting head, only to be electrocuted by a bug zapper; and Mother and Child Divided (1993), Hirst's Turner Prize-winning sculpture comprising four glass cases, two holding one half of a cow, split lengthways from nose to tail and two holding a calf similarly split, are two of the best examples. But many of the show's works tell us as much about Hirst as a businessman, and his impact on the curious economics of the art world, as they do about him as an artist.

In 2008 I wrote a book entitled The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, about the economics of contemporary art. The title was derived from Hirst's work, The Physical Impossibility of Death In The Mind of Someone Living (1991), a preserved tiger shark in a tank of formaldehyde. It was sold twice, in 1991 to Charles Saatchi for £50,000, and in 2005 to New York hedge-fund operator Steven A. Cohen, for a reported $12 million (£7 million). For each sale, the shark was the second most expensive work of that time by any living artist. Though since superseded, it is Hirst whose name comes up first in any discussion of the astronomical prices reached by contemporary art.

In 2007 he trumped himself, almost. For the Love of God (said to be the words uttered by Hirst's mother on hearing of his latest project), is a diamond-encrusted platinum cast of a human skull, fabricated by the Bond Street jeweller Bentley & Skinner: it will go on display in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall, surrounded by uniformed guards. Before completion, the skull had an extraordinary level of publicity for a work in progress, more than 100 newspaper and magazine articles preparing the art world for its theatrical first showing at White Cube gallery.

White Cube offered the work for £50 million, which would have outstripped by far the highest price achieved by a living artist. The skull sold. But it later emerged that the buyer was an investment consortium composed of Hirst, Jay Jopling, owner of White Cube (the gallery that represented Hirst), Frank Dunphy, Hirst's business manager at the time, and an outside investor, thought to be the Ukrainian industrialist Victor Pinchuk. It is now on offer for £100 million. A diamond expert estimated the worth of the stones at £7 million to £10 million. But the skull's real value is uncertain, even irrelevant. Several critics have argued that the price tag, sale and media coverage are part of the artwork.

For the Love of God is a one-off, but Hirst has cleverly managed to retain the value of his more ubiquitous works. His spot paintings are among the most recognisable contemporary artworks: grid arrangements of coloured spots on a white background. Hirst admits that 1,400 spot paintings have been sold worldwide; art insiders think the number may be closer to 2,200. And yet the spot paintings quickly became iconic - in ways no other artist could have got away with. In May 2003 a Hirst spot painting became the first work of art to be launched into space. It was incorporated as a colour calibration chart on the British Beagle 2 Mars lander, which crashed on the planet on or around Christmas Eve 2003. Another Hirst spot painting appeared in the Meg Ryan time-travel movie Kate & Leopold, representing the art of the 20th century. Spots have sold at auction for between £80,000 and £1.2 million To the victor, the spoils: Hirst's success enabled him to negotiate his dealer's commission at White Cube and Gagosian down from the standard 50 per cent to a reported 20 per cent on exhibitions and 30 per cent on sales from inventory. Making this arrangement public caused a few other artists to renegotiate. Others, trying to emulate Hirst, have probably undertaken acrimonious but failed negotiations with their dealers.

In September 2008 Hirst decided to bypass White Cube and Gagosian entirely to offer art from his workshops at Sotheby's in London. This unprecedented move circumvented the dealer system altogether. The auction included 223 works - dead sharks, zebras and a 'unicorn' (actually a foal). There were spot paintings, spin paintings, pinned-butterfly compositions and cabinets filled with drugs. The star lot was The Golden Calf, a bull preserved in formaldehyde, with 18-carat gold hooves and horns, a gold Egyptian solar disk on its head and outsized reproductive organs. It was sold on the phone, reportedly to a representative of Sheikha al-Mayassa, for £10.3 million. The very top end of the contemporary art world is small; she is chairwoman of the Qatar Museums Authority, which is funding the Tate exhibition.

Sotheby's waived its consignor's commission for the auction but retained the buyer's premium, so Hirst took home 100 per cent of the hammer price from each sale. Of the 223 lots offered, 218 were sold - for £111 million. In a coincidence that could not have served Hirst's marketing machine better, it began on the day that Lehman Brothers announced it was bankrupt.

The auction made a bold and, for the dealers, rather terrifying statement - that Hirst did not need the support of two of the art world's most important branded intermediaries. Other dealers described Hirst going directly to auction as 'the sum of all fears'; their concern was that other 'branded' artists, such as Jeff Koons and Takashi Murakami, might follow suit. So far no one has, but dealers are still wary. Media reports claimed that, over the following two weeks, 25 per cent of the buyers defaulted - by far the highest number in any Sotheby's or Christie's auction.

And yet Hirst continues at the top. In January Larry Gagosian's 11 galleries in seven countries held the first "worldwide one-artist exhibition" for Hirst, The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011. One can only speculate on the motivation, given Hirst's auction experiment. Probably Gagosian was responding to clients who had found no market for their Hirst paintings during the recession. Only 120 of the 331 paintings on display were nominally on sale; the others were said to be on loan from collections in 20 countries. No gallery official would tell visitors the prices, which were for sale, nor how many had sold.

In a typically Hirstian move, just before the opening of the show, Gagosian announced a "Spot Challenge", where anyone who visited all 11 galleries during the duration of the exhibition and had their card stamped at each, received a limited-edition personally dedicated Hirst print (the recipient got to choose the dedication). The value would be about $2,500, depending on how many were given out; 700 people signed up online for the challenge.

The Reuters blogger Felix Salmon estimated the cost, with business-class travel and good hotels, at $108,572. A columnist for The Art Newspaper, Cristina Ruiz, did it on an extreme budget and spent $3,250.75. The New York Times quoted one collector as saying: "I would only do it if I had no life, no job, someone else was paying my way and Scarlett Johansson came with me." The challenge was completed by 114 people (though none with Ms Johansson). I cannot imagine any other contemporary artist producing that result. And where Hirst leads, others follow: White Cube this month launched its own 'global' exhibition of 292 Gilbert & George pictures in its three London spaces and its new Hong Kong gallery.

Hirst understands diversification. He has evolved into a successful retail brand, with two branches of Other Criteria, a London store offering his limited editions and multiples, along with jewellery, clothing, towels and books. He is to become a property developer, having applied to build 500 eco-homes near his house in north Devon. He is a restaurateur: after his Pharmacy restaurant closed in 2003 (he sold its artwork for more than £11 million) Hirst opened 11 The Quay in Devon. And in 2014 he will open 'my Saatchi gallery': a London building to display 2,000 pieces from his personal collection, by him and artists including Francis Bacon and Banksy.

"Damien is totally fearless," says Oliver Barker, Sotheby's deputy chairman for Europe. "He's not just an outstanding artist, he's a cultural phenomenon."

Charles Saatchi says that Hirst is one of only four artists from the last half of the 20th century (with Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol and Donald Judd) who will not be consigned to the footnotes of art history 20 years hence. He is right. Regardless of whether you find Hirst's work rich and satisfying or shallow and irritating, he has an unparalleled commercial killer instinct. He not only understands the art market, he has single-handedly altered its axis.

Women In Art

-

MUCH fanfare greeted the $388m made by Christie's post-war and contemporary evening sale in New York earlier this month - its highest total ever. Few seemed to notice that the auction was unprecedented in another way: it had ten lots by eight women artists, amounting to a male-to-female ratio of five-to-one. (Sotheby's evening sale offered a more typical display of male-domination with an 11-to-one ratio.) Yet proceeds on all the works by women artists in the Christie's sale tallied up to a mere $17m - less than 5% of the total and not even half the price achieved that night by a single picture of two naked women by Yves Klein. Indeed, depictions of women often command the highest prices, whereas works by them do not.

An analysis of data provided by artnet, however, suggests that the prospects for women are slowly improving. Compare, for example, the top ten most expensive male and female artists. Admittedly $86.9m, the highest price for a work by a post-war male artist (set by "Orange, Red, Yellow" by Mark Rothko) dwarfs the highest price paid for a work made by a woman - $10.7m for Louise Bourgeois's large-scale bronze "Spider". However, of the top-ten men, only two are living, whereas among the top-ten women, five are still working.

"Attitudes are changing generationally," says Amy Cappellazzo, chairman of post-war and contemporary art development at Christie's. "It wasn't long ago that it was hard to be taken seriously as a woman artist. There will be some remedial catch up before women artists have parity on prices."

Compared to the top-ten post-war men, which includes a lot of American Pop and British figurative painters, the work of the top-ten women, particularly the deceased ones, leans heavily towards abstraction. Joan Mitchell, an abstract-expressionist painter who spent most of her adult life in France, is the sales turnover queen. Her work has accrued $199m at auction since the mid-1980s, when artnet records began. Mitchell's stature in the market results from an international collector base, which includes Russian, Korean, French and American buyers. Abstraction always aspired to being a universal language; perhaps the new global elite will make it so.

By contrast, the living women in the top ten are exceedingly diverse. Cady Noland, for example, who holds the record for the highest price ever paid for an artwork by a living woman ($6.6m), is a reclusive figurative sculptor whose work explores the sordid underbelly of the American dream. It has been over a decade since she has publicly exhibited her work, leading some to wonder whether she has stopped making art. Yayoi Kusama, however, an 83-year-old Japanese artist, has an oeuvre that spans five decades and a love of the media. Her work has the highest turnover of any living woman. Her monochrome "Infinity Net" paintings command the highest prices, but her colourful prints contribute to her high volume at auction. In July her profile will receive a boost due to her collaboration with Louis Vuitton on a ready-to-wear and accessories line. The exposure is likely to have a positive impact on her prices.

Cindy Sherman, a New York-based photographer, is a different style of artist again - one whose work is often interpreted as feminist. Last year an image from her 1981 "Centerfold" series set a record for the highest price ever paid for a photograph ($3.9m). Although a work by Andreas Gursky, a German photographer, has since displaced Ms Sherman's picture from the top spot, she is still one of the few women artists whose auction prices are in the same ballpark as her male peers. It is probably no accident that Ms Sherman works in a medium that has only recently been elevated to the status of art and is not overwhelmed by a legacy of male geniuses.

Intriguingly, the auction records for all three women - Mlles Noland, Kusama and Sherman - were the result of winning bids by Philippe Segalot, an art consultant who was then working for Sheikha Mayassa Al Thani, the Western-educated 29-year-old daughter of the emir of Qatar. It is probable that women feel a sense of affinity for art made by women. But perhaps more importantly, younger buyers and advisors find it weird to not include women's perspectives in their collections. It appears the future will be more female. And as Iwan Wirth, a dealer with galleries in New York, London and Zurich, puts it, "Women artists are the bargains of our time."

Almost 50 years ago, contemporary art dispensed with modernist myths that associated originality with heterosexual male virility. Openly gay men - such as Andy Warhol and Francis Bacon - fought that battle and won. Now three of the top-ten most expensive male artists are gay. In the 1960s most women artists shied away from trying to compete for sales, opting instead to focus on garnering intellectual credibility, which led them to rigorous abstract and conceptual-art practices. In the 1980s they started to branch out and diversify. Although increasingly celebrated by museums, women are still emerging when it comes to the art market.

An auction evening sale affords superlative marketing. Oftentimes the simple act of including a young artist, or an unknown older one, results in a high price. Whether their works move from being cultish lots to international trophies depends on collectors, but it's good to see the auction houses finally giving more women a chance. For money is a powerful symbol of cultural worth.

Invisible Art

-

There are two good things about the Hayward Gallery's celebration of invisible art, and one bad thing. Since the positives outnumber the negatives, it is right to start with them. I'll get to the problems later.

Good thing number one is that the subject is being tackled at all. Plenty of observers will dismiss the whole idea as a gimmick. The Hayward, alas, has lots of previous when it comes to artistic nonsensicality, and the current director, Ralph Rugoff, is renowned for the high scores he regularly achieves on the bullshit meter. But the fact is that many artists, across many artistic generations, have used nothingness in various ways to say various things. Ever since 1918, when the great Russian suprematist Kazimir Malevich painted his pioneering White on White - in which a white square was set against a white background - nothingness has been regularly reinvented.

One of the reasons I stopped attending student shows at Goldsmiths College is that I could not face seeing another blank wall presented as a radical exhibit by yet another copycat conceptualist. The worst winner of all time of the Turner prize was the tedious Martin Creed, in 2001, who showed us an empty room in which a light bulb went on and off, and that was all. It wasn't just the non-spectacle that was so irritating. Just as annoying was the thought that Creed had so many predecessors.

So invisible art has a busy history. And, had it been an easier subject to explore in an exhibition, it would have been explored before now. The difficulties involved in arranging a display of nothingness are obvious. The Hayward, in a very Rugoff gesture, has actually upped the ante by making the captions all but invisible, and by really going to town on the empty gallery look. The show only makes any sense if you look carefully, read carefully and think carefully as you stroll through the snowdrift.

Thus, Jeppe Hein's Invisible Labyrinth, from 2005, looks initially like a big empty room. Only when you read the instructions on the wall do you realise that the point here is to put one of the contraptions available at the back of the gallery on your head and wander out into the emptiness, with your headphones buzzing every time you choose the wrong path through an unseen maze. Sure to be an audience favourite, Invisible Labyrinth offers clear proof that authentic creatives will always find a new use for the empty room. It also illustrates how rapidly the divide is shrinking these days between the modern artwork and the funfair ride. (This is no place to expand on the need to entertain at any costs that is afflicting our cultural institutions, from Tate Modern to the BBC, but since that tendency is the direct result of putting audience numbers before principles, we should at least acknowledge that the Hayward has found an inventive way to dumb us down.)

If the first reason to admire the show is that it tackles a genuinely pertinent subject, the second is that it tackles that subject well, with verve and variety. Anyone who imagines that there is only one kind of white, or who expects all empty rooms to have the same effect, will have those views challenged by a display that leaps nimbly from blank to blank. Nothingness turns out to be a quality with many faces.

Yves Klein, who began exhibiting empty rooms in 1957, and who is the earliest creative nihilist examined here, appears to have had wacky religious reasons for his obsession with 'the void'. Even from the tiny fragments of archival evidence presented to us here, it is clear nothingness had a profound and cosmic presence for Klein. His empty rooms set out to confront, rather than avoid. The visitor to one of his 'architecture of air' displays was plonked in an expanse of Buddhistic whiteness that appeared to nurse ambitions to say it all.

The show only makes sense if you look, read and think carefully as you stroll through the snowdrift That is a very different effect from the cheeky consumer blankness created by Andy Warhol when he exhibited his Invisible Sculpture in 1985. By showing an empty plinth onto which he had once stepped, Warhol seemed to be celebrating his own vacant celebrity. We now know that the devious so-and-so was actually questioning the final value of celebrity per se: a work that appeared to be about him was actually about us.

Another form of absence explored by this surprisingly fertile event is what we might call memorial absence. It begins with Claes Oldenburg's proposal for a monument to John F Kennedy, consisting of a huge statue buried underground, so you cannot see it: a disappeared president is being commemorated by a disappeared artwork.

In the same spirit, the Mexican artist Teresa Margolles shows a white room into which two noisy air-conditioning units are pumping moist air. Only when you read the caption do you realise that the water cooling this air was originally used to wash the dead bodies of anonymous victims of Mexico's drug wars.

Just as all the empty rooms in the show have a different kind of presence, so the actual whiteness arrived at by a wide range of strategies is also varied. Bruno Jakob, who has apparently spent 25 years devising different means of making invisible paintings, gives us a crumpled white in which he once wrapped some potatoes, a blank white across which a snail has wandered and a glowing white created by a horse projecting its psychic energy onto the empty picture.

Under Rugoff, the Hayward has displayed a recurrent weakness for this kind of tricksy conceptual games-playing; and while the dreaded Martin Creed has been avoided, the show is not entirely devoid of silly ideas seeking to pass themselves off as deep ones. Jay Chung went as far as to shoot an entire movie with a full complement of crew and actors, but with no film in the camera. He has never told the cast or crew that their efforts were not recorded.

Most of this journey is set in the spectator's imagination. A typical exhibit describes a situation in a caption, then encourages you to think about it. As soon as you get it, off you go to the next puzzle. Thus, the problem with this event is, predictably, the shortage of interesting things here to look at. Rugoff has explained that the reason he wanted to do the show in the first place was that this is the summer of spectacles in Britain, and the situation appeared to him to cry out for a non-spectacle. Which he achieves too often.

Pasted on the wall outside the installation created by the art co-operative Art & Language is a long and complex description of their ambitions for the piece you are about to enter. When you walk into the room, however, you see immediately that it is empty. It only takes a moment for the point to be made. Five seconds of looking and you're off.

There is simply not enough here to savour. Not enough to watch at length. Not enough that pleases the eye. In a show devoted to various kinds of invisible art, the only really crushing sense of nothingness is the feeling left behind by the bad conceptual art.

Video Before YouTube

-

IT was the video that went viral before there was such a thing as viral video. Todd Haynes's "Superstar," released in 1987, was a darkly campy and experimental biopic about Karen Carpenter, who rose to fame with her brother, Richard, in the '70s pop group the Carpenters, and who fought a protracted battle with anorexia nervosa before her death at 32 in 1983. In the film characters were portrayed by plastic dolls, including Barbies, that looked as if they'd been plucked from a garage-sale free bin. Running 43 minutes, "Superstar" was a phenomenon, but not at the multiplex. It was shown primarily in galleries, museums and clubs, though it had a theatrical life at some repertory houses. Eventually it was copied and widely traded on bootleg VHS tapes, available for rent at alternative video stores across the country.

As filmmakers, distributors and exhibitors wrestle with the rise of digital platforms that let us watch movies on laptops and cellphones, it's worth remembering another time when advances in technology gave viewers the power to decide where and when they got their entertainment. VHS - short for Video Home System - set off a revolution in consumer entertainment when it was first introduced by JVC in 1976. It came down to convenience: Who needs a theater when a VCR turned every home into a cineplex? The era is explored in a retrospective, simply called "VHS," running through Aug. 19 at the Museum of Arts and Design at Columbus Circle. Far from an exhaustive survey, the series mostly consists of screenings of low-budget works like "Superstar" that demonstrate how VHS upended the system of making, sharing and consuming moving pictures.

That a museum is devoting attention to VHS is a nostalgic delight for fans like Nick Prueher, the author, with Joe Pickett, of the book "VHS: Absurd, Odd, and Ridiculous Relics From the Videotape Era" (2011).

"There are organizations dedicated to preserving the great films," Mr. Prueher said. "But there's no temperature-controlled vault with the Angela Lansbury exercise video. Those kinds of things will be lost forever if there aren't people hanging onto them." (As part of the retrospective, this month, the performance artist Jeffrey Marsh will host "Sweating to the Oldies," honest-to-god workout classes using original exercise tapes from home-fitness stars like Richard Simmons and Jane Fonda, and lesser-known Lycra fans like Elvira and Traci Lords.)

Buzz is high among VHS enthusiasts for the museum's July 6 screening of "Tales From the Quadead Zone," a 1987 horror anthology featuring a woman reading macabre stories to her phantom son. Poorly shot, badly acted and directed by Chester Novell Turner, a little-known filmmaker whose work also includes "Black Devil Doll From Hell," "Tales From the Quadead Zone" is a holy grail for VHS collectors.

"Copies of it surfaced all over, from California to New York, even though it doesn't look like it was made on this planet," said Matthew Desiderio, producer of the coming documentary "Adjust Your Tracking: The Untold Story of the VHS Collector." Mr. Desiderio is also an organizer of "VHS" with Jake Yuzna, the museum's manager of public programs, and Rebecca Cleman.

Just as the DVR replaced the VCR, digital advances have also meant that films like "Quadead Zone" and "Superstar" are no longer clandestine favorites but are freely available on YouTube, probably uploaded from pirated VHS tapes. But bootleg copies still circulate. "I don't know anyone who has seen "Superstar" on anything but VHS or online," Mr. Yuzna said. It wasn't just major studios who, after a cautious start, embraced the format at the time. Regular people began experimenting, said Mr. Prueher, who with Mr. Pickett runs the Found Footage Festival, a traveling show of oddball VHS clips. "It was like a gold rush," he added. "People for the first time could try out new things and be able to control movies in their home. Because the format was so cheap and readily available by the late '80s, you had people who would have had no business in front of or behind the camera making videos."

That wouldn't include Mr. Haynes, of course, who is now better known for helping establish the New Queer Cinema of the early '90s with "Poison" and for work like "Far From Heaven," which earned him an Oscar nomination. But it was "Superstar" that put him on Hollywood's radar.

Standing at the intersection of free speech, artistic appropriation and copyright law, "Superstar" exemplified how the VHS tape created what the film scholar Lucas Hilderbrand calls "new modes and expectations of access." As word about the Barbie-Karen Carpenter movie spread beyond the artistic underground and into the mainstream - slowly, this being the pre-digital age - its demise was sealed. Mr. Haynes got in legal hot water with the Carpenter family and A&M Records, the duo's label, for, among other things, using Carpenters' music without permission. Mattel, the maker of Barbie, wasn't happy either.

"It sounded much more meanspirited and cynical, to tell the story of Karen Carpenter with Barbie dolls, than the actual experience of watching the film," Mr. Haynes recalled. "I could see that would never be something they were comfortable with."

A settlement reached in 1990 prohibits "Superstar" from being sold, distributed or receiving any authorized exhibition, although Mr. Haynes said he retained some rights to show the film in the context of his other work. He said he was not aware of the Museum of Arts and Design screening. "The less I know probably the better," he added. Mr. Yuzna said he had 'reached out' to the Carpenters' estate and was "not told that there would be issues" with showing it.

Despite efforts to stifle "Superstar," it never really died. "In a way it's out of my hands," Mr. Haynes said. "The film has had its own life. It's something that no one can totally control and suppress."

Andy Warhol and Food

-

What do you get when you put a chocolate bar between two pieces of white bread? Andy Warhol called it cake.

Warhol's relationship to food is manifest not only in his art but also in the frugality and deprivation of his childhood, the time he was from - America in the 1930s, '40s and '50s - and in his flip philosophy and deadpan sense of humor.

Anyone with a slight interest in his work is aware of how prominently Campbell's Soup and Coca-Cola figure into his art. Some may own, or have at least seen, the first Velvet Underground album, which has a Warhol cover featuring a bright yellow banana. (You could actually peel the banana open on the original copies back in 1967.)

Dedicated fans of the pop artist might be familiar with his Kellogg's Corn Flakes Boxes and his Tunafish Disaster painting of 1963, which is based on a newspaper story about two older women who died from eating a can of tainted tuna. There's even a later Warhol series of works based on Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper.

The frequency of Warhol's food references declines in his '60s films. (It's possible that the actors in many of Warhol's movies don't eat because they were fueled by amphetamines, and speed freaks are notoriously indifferent to food.) Warhol's film Eating Too Fast, which is also known as Blow Job #2, is a sound version of BLOW-JOB, and is obviously not about food. Still, there are Eat (1964), starring Robert Indiana; Restaurant (1965), with Edie Sedgwick and Bibbe Hansen (future mom of Beck); and The Nude Restaurant (1967), filmed at the Mad Hatter on West Fourth Street, which had been a lesbian bar in the '50s called the Pony Stable Inn and is now the Washington Square Diner.

Among these films, Eat is the only one in which the activity of eating is primarily depicted. For the entire duration of its 45 minutes, Indiana silently and glacially consumes a single mushroom, and not of the psychoactive variety. When Warhol was asked why the movie was so long, he matter-of-factly said that was how long it took Robert Indiana to consume the mushroom. Warhol was probably the only director in the history of film who never said the word 'cut.'

And then there is the very curious Schrafft's Commercial (1969), described thusly by critic Harold H. Brayman: The screen fills with a magenta blob, which a viewer suddenly realizes is the cherry atop a chocolate sundae. Shimmering first in puce, then fluttering in chartreuse, the colors of the background and the sundae evolve through many colors of the rainbow. Studio noises can be heard. The sundae vibrates to coughs on the soundtrack. 'Andy Warhol for a SCHRAFFT'S?' asks the off-screen voice of a lady. Answers an announcer: 'A little change is good for everybody.'

Commissioning Warhol to come up with an ad for their restaurants was an attempt by Schrafft's to attract a hipper audience. Their image in the late '60s wasn't vastly different from how they had presented themselves in the late '50s. Tied in with the Warhol commercial was a new product, advertised on their menu as the Underground Sundae: "Yummy Schrafft's vanilla ice cream in two groovy heaps, with three ounces of mind-blowing chocolate sauce undulating within a mountain of pure whipped cream topped with a pulsating maraschino cherry served in a bowl as big as a boat." Priced at about a dollar, it was a pretty good deal.

What isn't seen in that 60-second spot is what Warhol superstar Joe Dallesandro recalls from the day it was filmed. He and Viva were in the studio, both topless, she spread out on a table, with Dallesandro smoking and standing behind her, his muscled arms modestly but provocatively covering her bare breasts. They were, of course, removed from the final cut of the commercial, but it's clear that Warhol originally wanted the sundae to have more than a cherry on top, and instinctively knew that sex helps to sell even the most dubious product.

Given that he was surrounded by all sorts of drugs and freaks throughout this period, it's surprising that Warhol's most psychedelic filmed moment is reserved for a sugary trip down memory lane - an ice cream sundae with all the extras. There's even an all-American take on the image to be found in an illustration of Warhol's from the '50s of a triple-scoop sundae whose glass boat is festooned with a little American flag on either side: a patriotic Fourth of July dessert.