Cars Articles

1. Cars As Investments

2. Hotrod Bugatti

3. Jeremy Clarkson On American Cars

4. Feedback Loops

5. Auctions

6. Transformer

7. Do you want more efficient cars?

8. Cars With Record Players

9. You Are What You Drive

10. Incentives To Change Behaviour

11. Pimp My Van

12. Customised Luxury Cars

13. Google Exec and His Supercars

14. Data and Poor People

15. Rod Stewart and Cars

16. Too Many Bikes

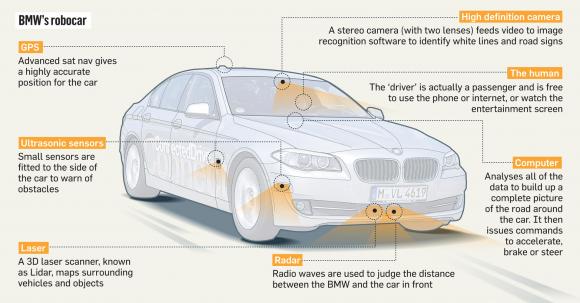

17. Self-Drive Cars

18. Texting

19. Pedestrians

20. New Technology

21. Driverless Cars

22. Cycling Risks

23. Racing Ferraris For The Rich

24. Wheel Clamps

25. Dashcams

26. The Beast

27. Cars Bikes and Cycles

28. eCall and Tracking

29. Best bargaining techniques when buying a car from a dealer

30. Jeremy Clarkson and Top Gear

31. The Economics of Self-Drive Cars

32. Hacking Car Computers

33. Google's Self-Driving Car Already Drives Better Than You Do

34. Google's Next Self-Driving Car: No Steering Wheel

35. GM's OnStar

36. Nudging Speeding Drivers

37. Automated Road Trains

38. Sandbox For Driverless Cars

39. Pedestrian Avoiders

40. Artificial Sound for Electric Cars

41. Google Image Recognition

42. Connected Cars

43. Singapore Driverless Cars Trial 2015

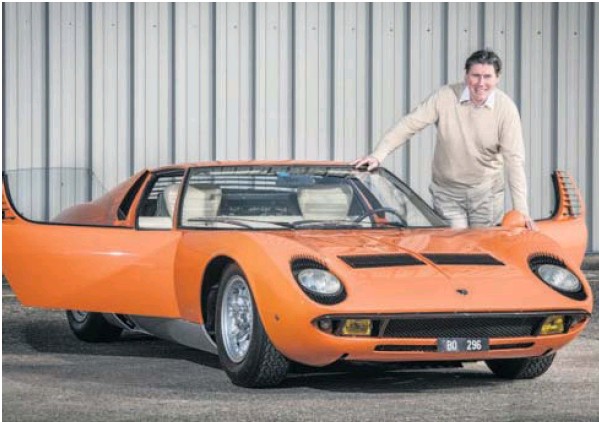

44. The Italian Job

45. Parking Fines

46. Incompetent Drivers

47. You Are What You Drive

48. Manufacturers Cheating On Emissions Tests?

49. Comparative Cost of Driving

50. AVs and Social Control

51. AVs as of 2022

52. UK Car Auction site

2. Hotrod Bugatti

3. Jeremy Clarkson On American Cars

4. Feedback Loops

5. Auctions

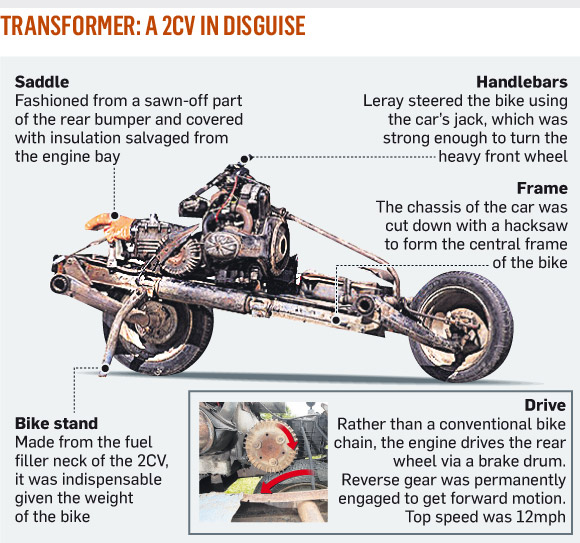

6. Transformer

7. Do you want more efficient cars?

8. Cars With Record Players

9. You Are What You Drive

10. Incentives To Change Behaviour

11. Pimp My Van

12. Customised Luxury Cars

13. Google Exec and His Supercars

14. Data and Poor People

15. Rod Stewart and Cars

16. Too Many Bikes

17. Self-Drive Cars

18. Texting

19. Pedestrians

20. New Technology

21. Driverless Cars

22. Cycling Risks

23. Racing Ferraris For The Rich

24. Wheel Clamps

25. Dashcams

26. The Beast

27. Cars Bikes and Cycles

28. eCall and Tracking

29. Best bargaining techniques when buying a car from a dealer

30. Jeremy Clarkson and Top Gear

31. The Economics of Self-Drive Cars

32. Hacking Car Computers

33. Google's Self-Driving Car Already Drives Better Than You Do

34. Google's Next Self-Driving Car: No Steering Wheel

35. GM's OnStar

36. Nudging Speeding Drivers

37. Automated Road Trains

38. Sandbox For Driverless Cars

39. Pedestrian Avoiders

40. Artificial Sound for Electric Cars

41. Google Image Recognition

42. Connected Cars

43. Singapore Driverless Cars Trial 2015

44. The Italian Job

45. Parking Fines

46. Incompetent Drivers

47. You Are What You Drive

48. Manufacturers Cheating On Emissions Tests?

49. Comparative Cost of Driving

50. AVs and Social Control

51. AVs as of 2022

52. UK Car Auction site

Cars As Investments

-

Classic cars are a very poor investment.

With the current economic turmoil, people are looking for safer investments, and some are buying up classic cars in the hope that these vehicles will gain in value. My advice is: don't. There's a widely held myth that classic cars never lose value and often increase in price.

This is basically crap. People who invested in classic cars before the 1987 stock market crash generally lost heavily on the deal. In some cases their vehicles lost three-quarters of their value.The Wall Street Journal recently reported a severe drop in the price of low to mid-range classic cars, as the owners were forced to unload them in the face of economic downturn.

Even upmarket marques like Ferraris are not immune. These cars tend to be bought during good times by people who have grown rich due to speculation on property or shares. When these investments drop in value, rich people suddenly aren't rich any more so they end up having to auction off their cars for far less than they paid for them.For example, a 2005 Ferrari 612 Scaglietti, with only 1000km on the odometer, recently sold at Turners Car Auctions for just $255,500, something of bargain considering it sold four years ago for $640,000.

The really rare classics are still reaching record prices because buyers see them as a hedge against economic recession. As long as there are more buyers than sellers for the really rare models, the high prices will continue.

However, if past experience is anything to go by, the current market will quickly turn around, when the sellers begin to outnumber the buyers.There will always be a few really rich classic car owners who can afford to wait for the recession to end, but there will be many more who are forced to unload their investments prematurely, at a loss.

This will signal to the market that the boom is over, which will lower the value of all similar classic cars.Houses have an intrinsic value simply because people need somewhere to live. Expensive classic cars have no intrinsic value, even as transport, because they're rarely driven - they're essentially expensive works of art. Classic cars have value only because people believe them to have value. As soon as this perception shifts, the asset can quickly become a liability.

For many less wealthy classic car enthusiasts, such as myself, their car is a part of their family. However, most owners will privately admit that they've spent far more on their classic than they could ever hope to get back by selling it.

If you take a classic wreck and fully restore it, you can expect to recover between one quarter and one third of the money you spent on it, not including a few thousand hours of your own labour.I've been restoring classic cars for over 20 years, and my general advice is that people should buy them because they love them, not because they want to make money from them.

Hotrod Bugatti

-

The Bugatti Veyron is, once again, the fastest production car on the planet.

Bugatti says an orange-and-black Veyron 16.4 Super Sport achieved an average top speed of 267.8 mph at the hands of test driver Pierre Henri Raphanel. Stop and think about that for a moment. That's more than 393 feet per second and almost 4.5 miles per minute. Even Bugatti's engineers were surprised.

"We took it that we would reach an average value of 425 km/h (264 mph)," chief engineer Wolfgang Schreiber said in a statement. "But the conditions today were perfect and allowed even more."

Raphanel made his record-setting run at Volkswagen's test track in Ehra-Lessien, Germany, in the latest version of the greatest automobile ever made. He had one hour to make back-to-back runs in each direction. The speedo hit 427.933 km/h against the wind and 434.211 with it. That came to an average of 431.072, which by our math is 267.8 mph.

And that was more than enough to take the title back from Shelby Super Cars and the Ultimate Aero, which had held the record since peeling off an average of 256 mph in 2007. Raphanel set the record on June 24; Bugatti announced it on July 4. Bugatti says Guinness was on-hand to verify the record, and we imagine the guys at SSC will not take this sitting down.

As the name suggests, the Super Sport is a hot-rodded version of a car that already has too much of everything. The 16-cylinder engine has been tweaked and tuned with bigger turbochargers (four, count 'em, four) and intercoolers. Bugatti says the engine is good for 1,200 horsepower and a staggering 1,106 pound feet of torque.

The carbon-fiber monocoque is stiffer yet lighter, the suspension has been stiffened and Bugatti says the car is capable of 1.4g of lateral acceleration. The body has been revised, and the engine draws air through a pair of NACA ducts in the roof instead of two big scoops.

Bugatti plans to begin building the Super Sport this fall. The first five off the line will be identical to the record-setting car. The remainder will have the top speed governed at 415 km/h (257.8 mph) "to protect the tyres," Bugatti says.

Jeremy Clarkson On American Cars

-

Today, if you want something to be a commercial success, it must be designed from day one with a passport and legs. Whether a beefburger, a plastic Doctor Who toy, a strawberry, an internet people-searching site or a sport, it must be as relevant in Alice Springs as it is in the Colombian jungle.

Funnily enough, however, the biggest problem is America - the only country in the world that calls football "soccer" and insists on playing rounders and netball instead. So, if you have developed, say, a pillow that absorbs dribble, you stand a better chance of selling it to a pygmy with a dinner plate sewn into his bottom lip, than you do to Wilbur and Myrtle from Sacramento.

It's a bit like the "special relationship" Tony Blair always talked about so much. The Americans can build a nuclear-missile warning station in Britain to protect them, but it makes us the ideal first-strike target. They can extradite people from Britain, but we can't do the same from them. They can get our immediate help in the Gulf, but we had to beg for assistance against the Nazis and the Argies. With America, the world is a one-way street.

We must have their computers, their jeans and their eating habits, yet there are more Made-in-Britain labels on the moons of Jupiter than there are in South Dakota. To the average American, 'abroad' is Canada or Mexico. Any further than that and you need Nasa. Over there, a Brit is simply someone to shoot by mistake. So it's certain that Hank J Dieselburger isn't going to be buying a jar of Bovril any time soon.

Nor will he be watching a British-made car show. Top Gear is screened all over the world, from remote Himalayan villages to the bullet-ridden boulevards of Lebanon. It is a genuine, bona fide export success. But in the US it is watched only by half a handful of expats who diligently follow BBC America, and a few torrentists on the interweb.

This is partly because, when it comes to motoring, the English language makes more sense in Albania than it does in Alabama. Almost every word in the Americans' automotive lexicon is different from ours, so when we talk about motorways, pavements, bonnets, boots, roofs, bumper bars, petrol, coupes, saloons, people carriers, cubic centimetres and corners, they have no idea what we're on about.

Our forward commanders can call in a tactical airstrike in southern Afghanistan and their pilots will know precisely what's needed. But review a Fiat Punto 'hatchback' on the 'bypass' and you may as well be speaking in dog. Even their gallons are as odd as their spelling of 'centre'.

Then there's the pronunciation issue. Jagwarr, Teeyoda, Neesarn, Hundy, Mitsuboosi, BM Dubya, V Dubya - it's all completely mangled.

However, while they don't understand our car show, when it comes to the cars themselves, the one-way street works in the opposite direction. Just six months ago, and for the first time ever, foreign car makers sold more vehicles in America than those made by Brad, Todd and Bud.

And what of American cars over here? Well, if we exclude Cheshire from the equation, most people in Europe would rather have syphilis than a Buick. We'll buy their Coca-Cola, their iPods and their Motown sound, but the cars that gave Motown its name? No, thanks. Driving an American car would be like making love to Jade Goody when you had a choice.

It's odd. Why can Bill Gates sell his binary numbers to the world when General Motors can't sell its cars? I wish I had the answer, because then I might understand why I don't want to own the Callaway Corvette I used on a recent trip to Los Angeles.

Callaway is an engineering company that has been tuning and fiddling with Corvettes since the year dot, sometimes without much success. The first example I tried, way back in the 16th century, was owned by a murderer and had two turbochargers. This made the engine extremely powerful. So powerful in fact that when I tried to set off, it turned the clutch into a thin veneer of powder and shot it like talcum powder into the wind. The murderer was extremely displeased with me . . .

Since then, however, Callaway has continued to beaver away, helped along by the average American's deep-seated belief that all cars can be improved by a man in a shed - understandable when the cars in question were made in Detroit. So today it makes the Corvettes that race at Le Mans (which they can't say properly either). Furthermore, Callaway has sheds all across America, and even in Germany.

It has become a big business. And I'm delighted to say it has stopped upping the power without uprating any of the other components.

The car I drove, a one-off demonstration vehicle, was garnished with an Eaton supercharger - chromed, of course - that was about the same size as Antigua. It's so big that a special bonnet with a huge hump in the middle has had to be fitted. In the past it would have got the car from 0-60mph . . . just once, before the chassis snapped in half and the wheels fell off.

Not any more. The car is fitted with Stoptech racing brakes, Eibach Multi-Pro suspension, wheels made from magnesium and carbon fibre, and other beefed-up components from the tip of its slender nose to the back end of its Plasticine arse (which they also can't say). So it's actually designed to handle the 616bhp produced by that force-fed V8, although the standard car, which is also available as a convertible, has 580bhp.

Yes, 616bhp is a lot. It's the sort of power you get from a Ferrari 599. And yet the car you see in the pictures this morning costs just over $92,500. At today's exchange rate, that's about 35p.

At first I was too jet-lagged to drive, so I tossed the keys to a colleague who was part gibbering wreck and part Michael Schumacher. We'd kangaroo away from the lights, stall, lurch up to about 400mph and then zigzag through the traffic like Jack Bauer in pursuit of a Russian nuke.

As a result, on our way back from Orange County to Beverly Hills, I snatched the keys . . . and had exactly the same problem. The clutch is like a switch and the gearbox like something that operates a lock on the Manchester Ship Canal. And if, by some miracle, you do get them to work in harmony, you are catapulted into a hypersonic, Hollywood blockbuster world of searing noise, bleeding ears and speeds so fantastic that you mark the instrument panel down as a born again liar. I absolutely bloody loved it.

Most European and Japanese cars these days hide their thrills behind a curtain of electronic interference and acoustically tuned, synthetic exhaust noises. Driving, say, an M5, is like having sex in a condom. Driving this Corvette is like taking it off.

Oh sure, it has the same problems that beset all Vettes. A dash made from the same cellophane they use to wrap cigarette packets, a sense it's been nailed together by apes, the finesse of a charging rhinoceros and the subtlety of a crashing helicopter. But the Callaway power injection masks all this in the same way that a dollop of hot sauce turns a slice of week-old goat cheek into a taste sensation.

On the El Toro airfield, deserted since it was attacked by aliens in Independence Day, it would slide and growl like it was the love child of Red Rum and a wild lion. On the snarled-up 405 on the way back to LA, it made rude gestures to other road users, urging them to take it on, knowing full well that it could beat just about everything up to a Veyron (pronounced 'goddam cheese-eating Kraut junk'). Then, when the traffic got too bad, we cut through downtown LA, where it pulled off the most fabulous trick of them all - absorbing the bumps and potholes that would disgrace even the Zimbabwean highways authority. Simply as a result of this, I have to say it's an even better car than Chevrolet's own hot Corvette, the Z06, which rides the bumps like a skateboard. Let us look, then, at the Callaway's strengths. It is ridiculously cheap, immensely powerful, much more comfortable than you would expect, beautiful to behold and blessed with handling that belies the fact that it was designed in a country that has no word for 'bend'. It also redefines the whole concept of excitement.

If I lived over there, be in no doubt that I would have one like a shot. It suits the place very well. It is Bruce Willis in a vest. Over here, however, I'd rather go to work in a scuba suit. As a car, it would work fine, apart from the steering wheel being on the wrong side. It would be fun. It would be fast. And unlike most American cars, it isn't even that big.

As a statement, however, I fear it would sit in the Cotswolds about as comfortably as Sylvester Stallone would belong in an EM Forster novel. It isn't brash - at least not compared with a Lamborghini. But like all American cars, it does feel that way. And a bit stupid, too.

Funny, isn't it. American cars, more than all others, are built to travel and yet that's the one thing they really don't do at all well.

Feedback Loops

-

In 2003, officials in Garden Grove, California, a community of 170,000 people wedged amid the suburban sprawl of Orange County, set out to confront a problem that afflicts most every town in America: drivers speeding through school zones.

Local authorities had tried many tactics to get people to slow down. They replaced old speed limit signs with bright new ones to remind drivers of the 25-mile-an-hour limit during school hours. Police began ticketing speeding motorists during drop-off and pickup times. But these efforts had only limited success, and speeding cars continued to hit bicyclists and pedestrians in the school zones with depressing regularity.

So city engineers decided to take another approach. In five Garden Grove school zones, they put up what are known as dynamic speed displays, or driver feedback signs: a speed limit posting coupled with a radar sensor attached to a huge digital readout announcing "Your Speed."

The signs were curious in a few ways. For one thing, they didn't tell drivers anything they didn't already know - there is, after all, a speedometer in every car. If a motorist wanted to know their speed, a glance at the dashboard would do it. For another thing, the signs used radar, which decades earlier had appeared on American roads as a talisman technology, reserved for police officers only. Now Garden Grove had scattered radar sensors along the side of the road like traffic cones. And the Your Speed signs came with no punitive follow-up - no police officer standing by ready to write a ticket. This defied decades of law-enforcement dogma, which held that most people obey speed limits only if they face some clear negative consequence for exceeding them.

In other words, officials in Garden Grove were betting that giving speeders redundant information with no consequence would somehow compel them to do something few of us are inclined to do: slow down.

The results fascinated and delighted the city officials. In the vicinity of the schools where the dynamic displays were installed, drivers slowed an average of 14 percent. Not only that, at three schools the average speed dipped below the posted speed limit. Since this experiment, Garden Grove has installed 10 more driver feedback signs. "Frankly, it's hard to get people to slow down," says Dan Candelaria, Garden Grove's traffic engineer. "But these encourage people to do the right thing.

In the years since the Garden Grove project began, radar technology has dropped steadily in price and Your Speed signs have proliferated on American roadways. Yet despite their ubiquity, the signs haven't faded into the landscape like so many other motorist warnings. Instead, they've proven to be consistently effective at getting drivers to slow down - reducing speeds, on average, by about 10 percent, an effect that lasts for several miles down the road. Indeed, traffic engineers and safety experts consider them to be more effective at changing driving habits than a cop with a radar gun. Despite their redundancy, despite their lack of repercussions, the signs have accomplished what seemed impossible: They get us to let up on the gas.

The signs leverage what's called a feedback loop, a profoundly effective tool for changing behavior. The basic premise is simple. Provide people with information about their actions in real time (or something close to it), then give them an opportunity to change those actions, pushing them toward better behaviors. Action, information, reaction. It's the operating principle behind a home thermostat, which fires the furnace to maintain a specific temperature, or the consumption display in a Toyota Prius, which tends to turn drivers into so-called hypermilers trying to wring every last mile from the gas tank. But the simplicity of feedback loops is deceptive. They are in fact powerful tools that can help people change bad behavior patterns, even those that seem intractable. Just as important, they can be used to encourage good habits, turning progress itself into a reward. In other words, feedback loops change human behavior. And thanks to an explosion of new technology, the opportunity to put them into action in nearly every part of our lives is quickly becoming a reality.

A feedback loop involves four distinct stages. First comes the data: A behavior must be measured, captured, and stored. This is the evidence stage. Second, the information must be relayed to the individual, not in the raw-data form in which it was captured but in a context that makes it emotionally resonant. This is the relevance stage. But even compelling information is useless if we don't know what to make of it, so we need a third stage: consequence. The information must illuminate one or more paths ahead. And finally, the fourth stage: action. There must be a clear moment when the individual can recalibrate a behavior, make a choice, and act. Then that action is measured, and the feedback loop can run once more, every action stimulating new behaviors that inch us closer to our goals.

This basic framework has been shaped and refined by thinkers and researchers for ages. In the 18th century, engineers developed regulators and governors to modulate steam engines and other mechanical systems, an early application of feedback loops that later became codified into control theory, the engineering discipline behind everything from aerospace to robotics. The mathematician Norbert Wiener expanded on this work in the 1940s, devising the field of cybernetics, which analyzed how feedback loops operate in machinery and electronics and explored how those principles might be broadened to human systems.

The potential of the feedback loop to affect behavior was explored in the 1960s, most notably in the work of Albert Bandura, a Stanford University psychologist and pioneer in the study of behavior change and motivation. Drawing on several education experiments involving children, Bandura observed that giving individuals a clear goal and a means to evaluate their progress toward that goal greatly increased the likelihood that they would achieve it. He later expanded this notion into the concept of self-efficacy, which holds that the more we believe we can meet a goal, the more likely we will do so. In the 40 years since Bandura's early work, feedback loops have been thoroughly researched and validated in psychology, epidemiology, military strategy, environmental studies, engineering, and economics. (In typical academic fashion, each discipline tends to reinvent the methodology and rephrase the terminology, but the basic framework remains the same.) Feedback loops are a common tool in athletic training plans, executive coaching strategies, and a multitude of other self-improvement programs (though some are more true to the science than others).

Despite the volume of research and a proven capacity to affect human behavior, we don't often use feedback loops in everyday life. Blame this on two factors: Until now, the necessary catalyst - personalized data - has been an expensive commodity. Health spas, athletic training centers, and self-improvement workshops all traffic in fastidiously culled data at premium rates. Outside of those rare realms, the cornerstone information has been just too expensive to come by. As a technologist might put it, personalized data hasn't really scaled.

Second, collecting data on the cheap is cumbersome. Although the basic idea of self-tracking has been available to anyone willing to put in the effort, few people stick with the routine of toting around a notebook, writing down every Hostess cupcake they consume or every flight of stairs they climb. It's just too much bother. The technologist would say that capturing that data involves too much friction. As a result, feedback loops are niche tools, for the most part, rewarding for those with the money, willpower, or geeky inclination to obsessively track their own behavior, but impractical for the rest of us.

That's quickly changing because of one essential technology: sensors. Adding sensors to the feedback equation helps solve problems of friction and scale. They automate the capture of behavioral data, digitizing it so it can be readily crunched and transformed as necessary. And they allow passive measurement, eliminating the need for tedious active monitoring.

In the past two or three years, the plunging price of sensors has begun to foster a feedback-loop revolution. Just as Your Speed signs have been adopted worldwide because the cost of radar technology keeps dropping, other feedback loops are popping up everywhere because sensors keep getting cheaper and better at monitoring behavior and capturing data in all sorts of environments. These new, less expensive devices include accelerometers (which measure motion), GPS sensors (which track location), and inductance sensors (which measure electric current). Accelerometers have dropped to less than $1 each - down from as much as $20 a decade ago - which means they can now be built into tennis shoes, MP3 players, and even toothbrushes. Radio-frequency ID chips are being added to prescription pill bottles, student ID cards, and casino chips. And inductance sensors that were once deployed only in heavy industry are now cheap and tiny enough to be connected to residential breaker boxes, letting consumers track their home's entire energy diet.

Of course, technology has been tracking what people do for years. Call-center agents have been monitored closely since the 1990s, and the nation's tractor-trailer fleets have long been equipped with GPS and other location sensors - not just to allow drivers to follow their routes but so that companies can track their cargo and the drivers. But those are top-down, Big Brother techniques. The true power of feedback loops is not to control people but to give them control. It's like the difference between a speed trap and a speed feedback sign - one is a game of gotcha, the other is a gentle reminder of the rules of the road. The ideal feedback loop gives us an emotional connection to a rational goal.

And today, their promise couldn't be greater. The intransigence of human behavior has emerged as the root of most of the world's biggest challenges. Witness the rise in obesity, the persistence of smoking, the soaring number of people who have one or more chronic diseases. Consider our problems with carbon emissions, where managing personal energy consumption could be the difference between a climate under control and one beyond help. And feedback loops aren'’t just about solving problems. They could create opportunities. Feedback loops can improve how companies motivate and empower their employees, allowing workers to monitor their own productivity and set their own schedules. They could lead to lower consumption of precious resources and more productive use of what we do consume. They could allow people to set and achieve better-defined, more ambitious goals and curb destructive behaviors, replacing them with positive actions. Used in organizations or communities, they can help groups work together to take on more daunting challenges. In short, the feedback loop is an age-old strategy revitalized by state-of-the-art technology. As such, it is perhaps the most promising tool for behavioral change to have come along in decades.

Auctions

-

THE collector car community left its annual week of auction extravaganzas here with much to think about.

After some uncertain years, have the value fluctuations caused by worldwide economic turmoil ended? Are the record-breaking sale prices limited to the finest and rarest vehicles, or will more common offerings also benefit from the rising tide?.

A total of 2,143 vehicles were auctioned at six events here, with total sales of at least $182 million, according to Hagerty.com, which tracks auction results for its collector-car price guide. One indicator - subject to the influence of available cars, to be sure - was the average sale price: $84,985, a healthy $17,142 higher than last year.

By genre, particularly strong sales were attained among European sports and racing cars like mid-1950s Mercedes-Benz Gullwings; rare classics like a Tucker Torpedo and a one-of-five 1933 Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow; and vehicles with celebrity provenance, like a 1932 Packard Twin Six roadster once owned by Clark Gable.

But over all there was strength, relative to recent years, from the top of the price ladder to the bottom rung.

"Our totals were only a couple million off from 2007," Craig Jackson, chief executive of the Barrett-Jackson Auction Company, said in an interview, referring to the peak year before the economy went into a tailspin. "It's coming back."

Barrett-Jackson's six-day event, the largest of the annual January auctions in the Phoenix area, accounted for more than half of the vehicles that changed hands during the week, with total sales of more than $90 million.

Barrett-Jackson's top sale was a 1948 Tucker Torpedo that brought a surprising $2.9 million. The previous record for a Tucker was $1.1 million at Monterey, Calif., in 2010. The marquee sale of the week, however, was by Gooding & Company, which sold a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Gullwing - one of just 29 produced with an aluminum body - for $4.62 million, a record for that type of vehicle. "It was aggressively estimated before the sale at $2.5 to $3 million," the president of the auction house, David Gooding, said in an interview. "Eyebrows were raised at that amount. But the sale absolutely soared past that. We had no idea it would do that well."

What might such a sale mean for the collector car market as a whole? "It is a strong but discerning market," Mr. Gooding said. "It's very, very strong for the best of the best. But average cars didn't set the world on fire." He added: "There is incredible strength for luxury brands from Europe, sports and racing cars especially, more post-World War II than prewar. Those vehicles are seeing very strong, high demand."

Even so, six auctions in town during the week may be one or two too many. Bonhams joined the party this year with a one-day event, while at auctions conducted by RM, Russo & Steele and Silver there was a drop from 2011 both in the number of cars consigned and in gross proceeds."I do see the scene as a bit diluted around the edges," Mr. Gooding said.

Even Gooding's catalog offered some vehicles a bit out of its usual range. These included a 1953 Simplex motorcycle and a garish 1948 Chrysler Town & Country convertible once owned by the actor Leo Carrillo of the 'Cisco Kid' TV series, that had a Texas longhorn head mounted on the hood. The longhorn's eyes even lit up, blinking left or right to signal turns. "Such a unique vehicle," the auctioneer, Charlie Ross, said with understatement.

At RM, notable deals included the $781,000 paid for a 1991 Ferrari F40 Berlinetta bought new by Lee A. Iacocca, the onetime Chrysler chairman, and the $990,000 sale of a 1959 BMW 507 roadster - one of only 251 built.

Barrett-Jackson, long considered a specialist in 1950s and '60s American sports and muscle cars, extended its reach in the other direction. The company's seven-figure sales - nine in all - included prewar classics from Daimler, Duesenberg and Isotta Fraschini. The high-end cars of Barrett-Jackson's new Salon Offering Collection are part of what it called the 5000 series, named for the special lot numbers assigned to them. These cars, which carried reserves of at least $500,000, included the Tucker and a 1947 Bentley Mark VI from the collection of Ron Pratte, a Phoenix-area businessman.

Thirty-five percent of the buyers at Barrett-Jackson's auctions were first-timers. "Businessmen are seeing how much potential there is in putting money into classic cars," Mr. Jackson said. "Where else are you going to put your money - in a bank?"

No small part of the Barrett-Jackson event's appeal is based on its six days of nationally televised programming on the Speed cable TV channel. "The 5000 Series cars brought in some excitement - and we are all about excitement," Mr. Jackson said. ""We could do small, European-style, one-day events only for a small, select group of high-end cars. But we prefer the large-scale American-style events. It's a lifestyle event now, with tours of the Phoenix area for our people who come in from out of town. We take the wives - more than 100 of them this year - shopping, golfing and to the casino. We have dinner and receptions. So do our sponsors."

On the other hand, the auction house is getting very picky about the vehicles it accepts, Mr. Jackson said. "We turned down a lot of cars this time." Cars were rejected, Mr. Jackson said, for not being in sale-ready condition; for the type of restoration or modifications done; and for those of questionable provenance. "When the amount of money we're talking about goes up, like it has, we see more phonies trying to get in," he said. "We have researchers who look very carefully into the claims of the consignors. If we find something that can't be substantiated, we bounce it back." Examples of questionable vehicles cited by Mr. Jackson include Pontiac Tempests that had been turned into GTOs and big-block Corvettes.

Surprising amounts were paid, particularly at Barrett-Jackson, for so-called resto-mods. These are not authentic classics, but modified vehicles - for instance, a 1957 Chevrolet gutted mechanically and fitted with a modern powertrain and suspension. "In some cases, these cars are getting prices that exceed even the values of the original versions of the cars," Mr. Jackson said. "These are collectibles you can actually use and drive."

Transformer

-

SACREBLEU! A Frenchman has found fame 20 years after pulling off the most unlikely conversion in motoring history. Emile Leray has become an internet sensation after photographs emerged showing how he dismantled a Citroen 2CV and turned it into a Mad Max-style motorbike after becoming stranded in the Moroccan desert.

The story of how he did it reads like a real-life version of a Top Gear challenge (think of the amphibious car). But this time there were no production staff hovering in the background, and for Leray the only prize was survival.

His adventure was the subject of a short news item on French television in the 1990s, but it remained largely unknown until last month, when photographs of the conversion appeared on a motoring website. They quickly went viral. Leray has been dubbed a real-life MacGyver - a reference to the 1980s American TV action hero who built improbable crimefighting machines out of everyday materials - and feted as the most extreme mechanic in the world.

The fuss has left Leray, now 62, a little stunned. "They refer to Mad Max and MacGyver and I see that there is a popularity chart and it is going up, but I am indifferent. I don't seek fame," he says at his home in a small village in northwest France.

"At that time, when I did it, there was no internet and I didn't publicise it. The news didn't circulate as quickly, and that's why now it is spreading more quickly. It is strange."

The tale began in 1993 when Leray, then a 43-year-old retired electrician with a thirst for adventure, decided to drive his 2CV from the town of Tan-Tan, in southern Morocco, to a remote village in the middle of the desert. "I wanted to do it off road because I had travelled round Africa about 10 times, so I knew the region well and therefore had no concerns," he says. "I decided to do it in a 2CV because, although it is not a 4x4, it is tough. In Africa they call it the 'Steel Camel' because it goes everywhere - provided you drive it gently. One must not be rough. I obviously was too rough because I broke it."

After being turned back at a military checkpoint and deciding to take a detour through the desert, Leray hit one of the large rocks that litter the terrain. The impact bent one of the wheel arms - the part of the 2CV's suspension that attaches the wheel to the axle - rendering the car undrivable. "I couldn't repair it -it was impossible. It was a big part that holds the wheel and it was broken. You need to go to a garage to repair that." It was late afternoon and the sun was beating down. Leray says he weighed up his options. He was almost 20 miles from the nearest village and he had some supplies: dates, tea, sugar, tinned food and onions that he had bought from the market in Tan-Tan, as well as enough water for several days. But he knew that he wouldn't be able to walk dozens of miles across the desert. "I could not have gone back on foot - it was too far. I put myself in what one calls survival mode. I ate less; I monitored my supplies of water and of food to make them last as long as possible."

The solution came to him that afternoon. Though he was not a trained mechanic, Leray had been a keen stock-car racer in France, and had had to repair his car every time he rolled it or crashed. "It gave me good schooling in mechanics and how to find solutions for things. So I decided to convert the 2CV because I knew it was possible," he says. The next morning he began dismantling the car, using a basic hacksaw. He used the 2CV's shell to shelter from sandstorms. Working in short sleeves, he adapted a pair of socks to cover his arms and protect them from the hot sun. He shortened the chassis and reattached the axles and two of the wheels, installing the engine and gearbox in the middle.

"I thought I would be able to convert the car in three or four days, but it took much longer than that. It took me 12 days. Things were more difficult to make than I thought. The accelerator and the clutch were complicated to make. Because of that, it took a long time."

The most frightening moment came at the end of the final day, when he finally managed to start the contraption. "That was the moment when I was most scared. I started the engine and I released the clutch - but I released it too quickly. The bike reared up and then it nearly fell on me." With just a pint of water left, Leray finally began the ride back to civilisation. Progress was painfully slow: the heavy bike bumped over the terrain and Leray often lost balance on the seat, which was made from part of the car's rear bumper. Even worse, he had no brakes. "I fell often, and at the end of the first day a part came loose and I had to stop to fix it. But by that point night had fallen, so I slept next to my machine in the desert," he says. In the morning, before Leray could continue, he was picked up by the Moroccan military. Was he relieved to be rescued? "Almost. But they issued me with a fairly hefty fine because they felt that the registration documents for the 2CV no longer corresponded to the bike. In their minds it was an offence. It was very expensive."

Today he is modest about his achievement and keeps his self-made bike in a barn in his village. "I took great pleasure in doing it but I don't consider it extraordinary," he says. "It surprises lots of people, but I tell you the Africans do things that are much more impressive." Even so, the interest in his tale has given him another bright idea: he wants to return to the desert with a friend to try to recreate the conversion job on video.

"I hope it would show people what they are capable of. Many people don't dare go travelling because they are afraid of breaking down. You shouldn't be afraid. Anything is possible."

People Say They Want More Efficient Cars, but ...

-

IMAGINE you are stopped in the street by a clipboard-toting pollster, who asks whether health insurance should automatically cover all necessary procedures and medication, with no restrictions or co-payments? Nine out of ten people (if not all) would instantly answer yes. But had the respondents been warned beforehand that they would have to stump up an extra $10,000 for such coverage, the answer could easily have been a resounding no.

Sad to report, this kind of selective polling - in which only the benefits are mentioned so as achieve a desired result - is cropping up increasingly in the support of various agendas. Substitute motor manufacturers for health insurers and fuel efficiency for medical treatment in the thought experiment above, and you have the kind of 'grassroots justification' that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) are using to push through a doubling in the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) figure motor manufacturers must achieve or face stiff penalties. The new proposal requires the fleet-average for new vehicles sold in America to rise incrementally from today's 27mpg (8.7 litres/100km) to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025.

The most effective endorsement for the new CAFE proposal comes from a national survey carried out last October by Consumer Reports (a highly respected non-profit organisation based in New York) which claimed that 93% of the 1,008 people interviewed by telephone wanted higher fuel economy and would pay extra for it. The survey results were released the day before the government announced its new CAFE proposal. Ever since, the poll has been considered hard evidence that the new CAFE proposal is widely supported by the American people.

Like all polls, when people are asked personal questions, they do not necessarily tell the whole truth. Indeed, most respondents provide the kind of answers they consider socially acceptable. In some cases (how often do you brush your teeth?) the response is inflated; in others (how much do you drink?) it is deflated. It is a well-known phenomenon, called 'social desirability response bias', which has been studied by sociologists and market researchers for decades and requires questionnaires to be structured in highly specific ways to minimise inbuilt biases.

"So, when consumers say fuel economy is extremely important, they are not lying," says Jeremy Anwyl, vice-chairman of Edmunds.com, the most popular source of independent car-buying advice used by American motorists. "The survey has just not allowed (or required) them to point out that other attributes are even more important."

Deciding what new car to purchase is a complicated undertaking, requiring all sorts of rational and emotional compromises. There are emotional factors to take into account, such as brand image, luxury, sportiness and appearance. Then there are physical features like comfort, number of seats, cargo space, body type and towing capacity. For most people, price and fuel economy represent costs.

In testifying before Congress last year, Mr Anwyl explained that "consumers are happy to pay less, or save fuel, but not if it means giving up features they deem important." A market simulation model that Edmunds has developed over the years indicates that fuel efficiency accounts on average for about 6% of the reason why consumers purchase a particular vehicle. Fuel efficiency only becomes important when petrol prices suddenly start climbing, but then declines in significance when pump prices stabilise or start to fall.

Here, then, is the conundrum: if the vast majority of motorists in America claim to want higher fuel economy and are prepared to pay for it, why are they not doing so? There is no shortage of cars already on the market capable of 40mpg or more. The Toyota Prius gets 50mpg on the EPA's combined cycle, while electric vehicles like the Chevrolet Volt and the Nissan Leaf deliver the equivalent of 60mpg and 99mpg respectively.

Yet few people are buying them. Despite large tax incentives for buyers, Volt and Leaf sales have fallen well short of even their manufacturers' modest expectations. Altogether, hybrid and electric vehicles account for only 2% of America's new car market. The government may mandate manufacturers to produce fuel-efficient vehicles, but it cannot mandate motorists to buy them.

The problem is their higher purchase price. Take the Toyota Camry, which is available in directly comparable hybrid and conventional forms. The hybrid version costs typically $3,400 (or 15%) more than the standard car, but achieves 13mpg (or 46%) better fuel economy. Even so, there have been few takers for the petrol sipper. Last year, Toyota sold over 313,000 ordinary versions of the Camry compared with fewer than 15,000 hybrid versions, notes Mr Anwyl.

The official line is that owners recover the premium on a hybrid or electric vehicle through lower running costs - with payback times of anything from four to seven years, depending on fuel prices. Unfortunately, American motorists tend to trade their new vehicles in after three to four years, and so do not collect anything like the full payback. Besides, the Edmunds model of consumer-buying habits (with 18m visitors a month, the website collects more data on such transactions than even the manufacturers) shows that consumers demand a payback period of 12 months or less.

What, then, to make of the new CAFE proposal? Achieving a fleet-average of 54.5mpg is doable, say motor manufacturers, but it will not be cheap. The NHTSA puts the cost of the extra technology (eight-speed transmissions, direct-fuel injection, turbo-charging, hybrid drives, larger batteries, electric power steering, low-rolling-resistance tyres, better aerodynamics, heat-reflecting paint and solar panels) needed to achieve the target at a modest $2,000 per vehicle, with a lifetime saving on fuel costs of $6,600 (provided fuel prices do not decline).

At the other extreme, the National Automobile Dealers Association reckons all the additional technology needed to achieve the 2025 goal will add $5,000 to the price of a new vehicle. Take somewhere in between - say, the $3,400 premium that Camry hybrid owners pay - and any lifetime savings through lower running costs look even more difficult to recoup.

Much, of course, depends on what fuel prices do over the ensuing years. And that includes the price of coal and natural gas as well as oil. Remember, most of the new electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids that carmakers will have to build to meet the new CAFE requirements will be recharged overnight using electricity from power stations that mostly burn dirty coal or (if people are lucky) cleaner natural gas or uranium oxide.

The good news is that the bonanza in domestic discoveries of natural gas should help keep the lid on fossil-fuel prices for years to come. And if fuel prices come down in real terms, that will hurt sales of fuel-efficient vehicles.

Indeed, the way the NHTSA and the EPA have skewed the relief manufacturers get on vehicles of different sizes will pretty well ensure that American motorists will, once again, opt for trucks and SUVs rather than Prius-like vehicles. The deal done to buy off the industry's opposition to the new CAFE requirements granted manufacturers special credits for certain fuel-saving technologies. Meanwhile, pick-up trucks and larger SUVs were given what effectively amounts to a free pass.

The degree to which a vehicle has to comply with the NHTSA's fuel-efficiency and the EPA's carbon-emission requirements depends on the vehicle's 'footprint' on the road. The larger the area (measured by multiplying the vehicle's track by its wheel-base), the greater the relief.

This was the fix that got Detroit's big three - which still rely on trucks and SUVs for the bulk of their profits - on board. No wonder Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz have complained bitterly about the deal, while General Motors, Ford and Chrysler have now come out in support of the new CAFE proposal. An added sweetener for American manufacturers and trade unions was to exclude credits for the extremely frugal diesel engines that European carmakers have spent billions perfecting.

All told, then, will motorists across the country be getting 50mpg or more by 2025? Hardly. For a start, there is a world of difference between the testing methods used by the NHTSA for CAFE purposes and the EPA for determining a vehicle's fuel-economy figures for the window sticker that new vehicles must display in dealers' showrooms. Because of the difference, consumers will be paying for technology needed to achieve a CAFE average of 54.5mpg, but will be buying vehicles that achieve a real-world average of around 36mpg.

That assumes the CAFE target will still be in place by then. Because there is a limit to the number of years ahead for which the NHTSA can set fuel-economy standards, the new CAFE target will have to be reviewed by all parties in 2019. By then, much could have changed - in terms of energy price and availability, as well as engineering. Though a long shot, a breakthrough in storage technology would alter everything.

And by then there will, of course, be a new Administration in the White House with, quite possibly, an entirely different agenda concerning energy and the environment. As much as anything, insiders reckon the possibility of being let off the hook by a new Administration was the clincher that persuaded the motor industry to go along for the ride.

You Are What You Drive

-

AFTER 11 years of daily use, the family kidmobile is nearing the end of its economic life. Meticulously maintained, it still runs fine. Or, rather, it does now the air-conditioning system has been overhauled - at greater expense than the car is actually worth. With the vehicle fully depreciated, the annual cost of ownership has been minimal for the past four or five years, but is now set to rise - as one electronic module after another can be expected to give up the ghost and need replacing at $1,000 or more a pop. Sadly, the time has come to contemplate putting the trusty old war-horse out to pasture. But what on earth to replace it with?

Purchasing a new car is the sort of emotionally draining experience your correspondent dreads. Perhaps that is why he keeps his cars so long: he has owned one of the two old Lotuses in his garage for 40 years, having built it from a kit in 1972; the other one he has had for the best part of 24. As a replacement for the kidmobile, he knows what he ought to buy, but is torn over what he would like to have instead.

There is a clever compatibility tool called My Car Match on Edmunds.com, a popular site for American motorists seeking advice on what to buy and how much to pay. The algorithm presents users with a series of questions about their needs and preferences - how many people the vehicle will have to carry, how much luggage, what type of vehicle, what price range. Each time, users are asked to select the best out of three vehicles presented, while the list of possibilities is repeatedly refined.

After going through all the hoops, your correspondent was told he should buy a Kia Soul, when he had hoped it would recommend at least a more up-scale Hyundai Genesis. So much for inflated aspirations.

Car buyers should examine their needs rather than their wants, Philip Reed of Edmunds.com points out. "In too many cases, people choose a car for its styling or because it is a trendy favourite," he notes. But that implies consumers can easily ignore all the subliminal signals coming from those structures in the brain that are responsible for predicting the outcome of decisions and providing emotional rewards.

In his book 'Engines of Change: A History of the American Dream in Fifteen Cars', Paul Ingrassia, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, pointed out how American culture has long been a tug of war between the practical and the pretentious, the frugal and the flamboyant, hot-wings and haute cuisine. Your correspondent believes that applies not just to America, but is probably universal - a crucial aspect, no less, of human nature.

More than anything else people purchase, a car broadcasts so much about who they are - or, rather, who they like to think they are. The whole business is fraught with stereotypes, often amusing, rarely meaningful, but once in a while spot on. For instance, Bentley nowadays implies 'footballer's wife'. Cadillac screams 'old codger trying to look cool'. Honda mutters something about being reliable but boring. Mercedes-Benz says simply 'taxi' in Europe and the Middle East, and 'too old for a BMW' in America. Porsche is code for 'desperate male having a mid-life crisis'.

With 45% of the cars on American roads being imports, there is also the nationality of the car to consider. Long ago, in his extremely amusing book 'How to Repair Your Foreign Car: A Guide for the Beginner, Your Wife, and the Mechanically Inept', Dick O'Kane listed some of the quirks of foreign cars and what such things implied about their owners. Thus, the British build cars that need to be tinkered with regularly. The Swedes make strapping vehicles that will ride over, under or through any obstacle. The Germans manufacture technological marvels, which, when they break, have to be taken to a high priest from the factory for repair. The French, ah the French, who can understand the French?

For most motorists, the trickiest part of buying a new vehicle is deciding which brand. The one that commands the greatest loyalty in America today is (no kidding) Hyundai. In this year's annual survey of car-brand loyalty by JD Power and Associates, a market-research firm in California, 64% of Hyundai owners said they would replace their existing vehicles with another of the same make. Ford, Honda, BMW and Kia were runners up in the loyalty stakes.

But brand loyalty is not what it used to be. Female buyers have become particularly fickle. So have the well-heeled who buy executive and luxury models. However, it is the young - the Gen X and Gen Y buyers - who are the most capricious. Nowadays, over half of motorists replace their present vehicles with another make. They do so because either the manufacturer does not offer the type they want, or they have been put off by a bad experience with their current car.

Another reason why loyalty has lost ground is because, these days, it is rarely rewarded. Existing customers can pay thousands of dollars more than someone switching from another make. Brand loyalists tend to haggle less, and car salesmen take advantage of the fact. Moral: if you want another Ford, do not drive up to the dealership in your existing one.

Loyalty aside, what a brand actually says about a carmaker is quite a different matter. If a brand does its job well, it links the consumer to the product being purchased by building an emotional image or bridge between the two. Either way, the product's brand-image and the consumer's self-image merge into a single entity that rewards the buyer with feelings of certainty and satisfaction.

The car-brand perception survey conducted annually by Consumer Reports National Research Centre in New York scores how consumers view each brand in seven particular categories: safety, quality, value, performance, environment, design and innovation. Combining the scores for each category gives an overall ranking that reflects the image consumers have in their minds of the manufacturer. The survey is reckoned to be particularly good at shedding light on what brands consumers are likely to purchase.

This year, the survey of brands people are most likely to buy once again lists Ford, Toyota, Chevrolet and Honda (in that order) at the top of the list. These four brands were singled out by more than half the people who participated in the survey. Even so, all the leading brands have seen their scores slip over the past year as high petrol prices, the woeful economy, huge recalls and other glitches have all taken their toll on brand values. And while safety used to be the most important consideration, followed by quality, value and performance, penny-pinching customers now prize low operating cost and reliability above all else.

So, what car should your correspondent buy? For a start, he needs five seats, with enough cargo space for the odd weekend trip. As the bulk of the driving is done in heavy traffic, an automatic transmission is essential. Neither all-wheel drive nor four-wheel drive (they are different) is necessary, as he rarely goes off road deliberately and has not encountered snow in ages. His brain says be sensible and buy a new Ford Fusion, which will be in the showrooms shortly.

But his heart lusts after the 1965 S-type rotting away in a local Jaguar repair shop. He had a second-hand 3.4-litre S-type (the current kidmobile's direct ancestor) half a lifetime ago, and ran it lovingly until both he and the car were broke. He has half a mind to do the same again.

Incentives To Change Driving Behavior

-

London, Singapore, Stockholm and a few other cities around the world battle heavy traffic with a congestion charge, a stiff fee for driving in crowded areas at peak hours. But drivers generally hate the idea, and efforts to impose it in this country have failed.

Balaji Prabhakar, a professor of computer science at Stanford University, thinks he has a better way.

A few years ago, trapped in an unending traffic jam in Bangalore, India, he reflected that there was more than one way to get drivers to change their behavior. Congestion charges are sticks; why not try a carrot?

So this spring, with a $3 million research grant from the federal Department of Transportation, Stanford deployed a new system designed by Dr. Prabhakar's group. Called Capri, for Congestion and Parking Relief Incentives, it allows people driving to the notoriously traffic-clogged campus to enter a daily lottery, with a chance to win up to an extra $50 in their paycheck, just by shifting their commute to off-peak times.

The program has proved so popular that it is to be expanded soon to also cover parking.

Amaya Odiaga, the director of business operations for Stanford's physical education department, now drives to campus a few minutes earlier and says she has won just $15. But a co-worker got $50 - creating a competitive atmosphere that makes the program fun, Ms. Odiaga said.

Better yet, Ms. Odiaga's commute now takes as little as 7 minutes, down from 25 minutes at peak hours.

Dr. Prabhakar is a specialist in designing computer networks and has conducted a variety of experiments in using incentives to get people to change their behavior in driving, taking public transit, parking and even adopting a more active lifestyle. Unlike congestion pricing, which is mandatory for everyone and usually requires legislation, "incentives can be started incrementally and are voluntary," he said.

Moreover, systems based on incentives can offer a huge advantage in simplicity. Until recently, the Stanford system required sensors around campus to detect signals from radio-frequency identification tags that participants carried in their cars. But the need for such an infrastructure has vanished now that so many drivers carry smartphones with GPS chips or other locaters.

Administrators can use the network to set up a centralized Web-based service to manage any number of incentive campaigns.

"Through smartphones we're getting more at ease about fine-grained information about space and time," said Frank Kelly, a mathematician at the University of Cambridge in England who specializes in traffic networks. "This is possible because information and communications systems are becoming cheaper and cheaper."

Samuel I. Schwartz, a transportation consultant and former New York City traffic commissioner, says a smartphone-based system is inevitable, though he predicts it will be used for congestion pricing as well as incentives.

"Ultimately we will be charged, or money will be added to our accounts, by using the cloud infrastructure," he said. "It's so precise that you will be able to charge people for how much of Fifth Avenue they use and for how long a period. In Christmas season you may decide to charge them $10 to use Fifth Avenue for each block."

In New York City, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg's plan for congestion pricing died in 2008 for lack of support from the state Legislature. Pravin Varaiya, an expert on transportation systems at the University of California, Berkeley, said enforcement costs would have been huge, adding that "carrots, as opposed to sticks, frequently work very well."

Still, Charles Komanoff, a transportation expert who has designed a computer model of New York traffic, said he had reservations about such a system as an alternative to congestion pricing.

"The incentives will be far too small," he wrote in an e-mail, adding: "You really do need big disincentives (big sticks). Little carrots won't do the job of changing drivers' decisions" in New York or in San Francisco."

Dr. Prabhakar said congestion pricing and his incentive system need not be mutually exclusive, and he noted that highway congestion was an example of nonlinear behavior, in which even a small reduction in vehicles at a given time - 10 percent or less - can have a big effect on traffic flow.

And conversely, added Dr. Kelly, the mathematician, "when the system is close to critical levels, very small increases in traffic can create time delays for everyone."

Dr. Prabhakar's experiments have offered different kinds of incentives, from airline-style reward points to lottery cash prizes. Now his system is poised to reach a much larger audience.

Singapore is considering a system he and his students designed that offers lottery participation or a fare discount to public transit riders who travel at off-peak times. A trial run begun in January lowered rush-hour ridership by more than 10 percent. (Given a choice between discounts and lottery, riders overwhelmingly chose the lottery.)

Bill Reinert, an advanced technology manager at Toyota, says incentives are no panacea. "Incentives the government gives you" to buy hybrid vehicles "are a good way not to establish markets," he said. But he added: "Do incentives work? Yes. I fly 300,000 miles a year on United."

The Stanford experiment adds a social network component to the lottery, in effect making it a game where friends can observe one another's 'good' behavior. The researchers say this tends to reinforce changes in behavior and individual commitment. Next fall, the university plans to expand the system to encourage people to park farther from the busiest parking structures.

The idea of using incentives to change social and personal behavior has grown increasingly popular. In their 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness, the economist Richard H. Thaler and the legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein argued that organizational structures could be created that guide people toward better behavior.

Dr. Thaler noted that variable tolls, like those used on the Hudson River crossings in New York at different times of day, "are clearly an attempt to shift people's incentives." Of traffic systems like Stanford's, he said, "this is just as efficient."

Dr. Prabhakar's first experiment was in Bangalore in 2008, when he created a system to encourage employees at the software company Infosys to choose different travel times to its suburban campus. The system significantly lowered congestion.

More recently, he worked with Accenture, a business services company, to set up a system that used pedometers to measure the number of footsteps more than 3,000 employees took each day, encouraging them to walk more for better health. The campaign, called 'Steptacular,' included a social network component and a Web-based game to add a random element to the incentives; it handed out $238,000 in rewards.

Dr. Prabhakar said the power of his method was that only a small change could have a drastic effect.

"This is one of the nicer problems," he said. "You don't have to change everyone's behavior; in fact, it's better if you don’t."

Pimp My Van

-

First it was stretch limos, then it was enormous Hummers and more recently it has been the eco-friendly Toyota Prius — but now Hollywood has turned to an even more surprising means of transport. Vans have become the must-have accessory for stars including Bruce Springsteen, Beyoncé and Will Smith, but rather than boasting about their wheels, celebrities are using them to drive around incognito. The best-kept secret on Sunset Boulevard, these vans are the perfect way to fool the paparazzi and avoid flaunting one’s wealth at a time when most people are tightening their belts.

The vans aren’t quite what they seem, though. Although they look ordinary from the outside, they pack more technology and creature comforts than your average living room, including airline-style leather reclining seats complete with massage functions, built-in iPad consoles, HD plasma screens connected to the web — enabling video on demand — and even refrigerated cupholders.

It is not just in Hollywood that the craze is taking off: in Britain one company says that it has been inundated with orders for the vehicles from businessmen and sportsmen keen to keep a low profile in austerity Britain without sacrificing the opulence of more traditional luxury cars. “They just want a little bit of privacy,” says Dayne Bartlett, owner of Touch of Class, a south Wales company that specialises in converting vans such as the Volkswagen Transporter and Mercedes Sprinter.

“No one really knows who’s inside, and that’s just the way they like it. We’ve done vans for at least four British celebrities that we can’t talk about.”

One of the company’s customers is the film director Guy Ritchie. Bartlett redesigned the interior of his white van as a gentlemen’s club, with brown leather armchairs, walnut flooring, brass fixtures and a tweed roof lining. “That was exceptional,” says Bartlett, “but the key thing is that we can do almost anything, from a £2,000 job all the way up to whatever your budget might be.”

In America the conversions are even more extreme. Justin Bieber’s new Mercedes Sprinter “party van” has three HD video screens and a massive sound system, while the rapper Snoop Dogg — who has now taken to calling himself Snoop Lion — has a gleaming black van containing a fully functioning mobile recording studio.

“Part of the Sprinter’s appeal is that it’s more anonymous than a Cadillac — it doesn’t attract undue attention,” says Howard Becker, founder of Becker Automotive Design in Los Angeles. He has converted dozens of the Mercedes vans into inconspicuous “JetVans”, so called because he aspires to match the quality and ambience of a sleek corporate jet. His clients have included Tiger Woods, Jay-Z and Eminem.

According to Becker, the craze for vans started when Hollywood stars began to experience limo fatigue. “An American stretch limo is so passé these days,” he says. “It’s ugly and uncomfortable and has become something schoolkids take to their prom night.” The same goes for Hummers. Even hybrids are losing their lustre. Travelling incognito in a van allows celebrities to criss-cross town in comfort without hordes of paparazzi on their tails.

The Sprinter van is big enough to seat up to seven in massaging seats with electric foot rests, personal HD TVs and desks with mobile broadband. Alternatively, musicians spending a lot of time on the road can opt for a micro-sized mobile home interior. The R&B producer The-Dream installed a shower, sink, cooker, microwave, coffee maker and bed in his Sprinter.

Where the famous go, the rich soon follow. One of Becker’s corporate clients requested a webcam and exercise bike so he could spin away while video-conferencing employees from a traffic jam. Other buyers, including some Middle Eastern royals, insist on armour plating, GPS tracking and other, unspecified, “emergency equipment”.

Prices for converting a Sprinter range from £2,000 for a couple of extra seats to £200,000 for the full JetVan treatment. Installing electronics such as massive flatscreen TVs, surround-sound systems, LED lighting and 4G-connected computers means adding circuit breakers, extra batteries and a beefed-up air-conditioning system.

Deluxe fittings such as electrically cooled seats and rare wood finishes can bump the total higher still. Becker even claims he has developed a ventilation system that can prevent car sickness by pumping bursts of filtered fresh air into the rear of the van.

For the ultra-rich, there can never be enough luxury or privacy. Becker is watching Google’s experiments with robotic cars eagerly. “I can’t wait for vans that drive themselves. It’s an interesting long-term vision,” he says.

The danger is that by the time robot chauffeurs arrive, luxury vans will have fallen from fashion. Already, a company called Brilliant Transportation has fleets of Sprinters for hire in New York and LA. The vans boast leather recliners, wi-fi, satellite TV, twin HD screens and hardwood floors, and cost from £130 an hour. Schoolgirls on their way to prom nights cannot be far off.

Customised Luxury Cars

-

For the super-rich, owning the latest luxury car is not enough. Now they are ordering paint jobs to match their pot plants and upholstering their seats in salmon.

Three of the Rolls-Royces in Michael Fux's fleet

Three of the Rolls-Royces in Michael Fux's fleetThose living around the Prime One Twelve restaurant in Miami Beach, Florida, are used to seeing the odd exotic car. After all, its clientele includes Cameron Diaz, Kim Kardashian, Bill Clinton and other wealthy types.

Lamborghini or Bugatti? Park it round the back with the others. No, it takes something special to draw crowds of onlookers - something like a bright purple Rolls-Royce convertible with yellow leather interior. Michael Fux, its multi-millionaire owner and a regular at the restaurant, has dozens of similarly outlandish cars among his of collection of 125.

While most people worry about arriving at a party in the same outfit as another guest, the mega-rich have nightmares about arriving in the same car, and increasingly they want something unique.

"I gave the manufacturers a challenge," says Fux, 69, who made his money in mattresses (see below). "I saw a purple pansy, and I gave it to Rolls-Royce and said, "I want you to match this"." The result was another one-off purple Phantom Drophead, with a white leather interior and a chrome nameplate stating that the car was built for Fux. He has now ordered a McLaren MP4-12C Spider in the same shade - once the company had signed an agreement that it wouldn't supply the same colour to anybody else.

"I told them I want the new P1, but I haven't worked out the colour I want it yet," says Fux. "Hopefully I will be ordering the new Enzo Ferrari, too. I'm planning to go to Italy to look at it."

Before those cars, he will take delivery of two new Ferrari F12s: a standard version and a customised version that will take up to a year to design and build.

High-rolling customers such as Fux have boosted demand for personalised cars, defying the world economy. Rolls-Royce has tripled the size of its bespoke design department in 18 months; Ferrari's Tailor-Made service, launched last year, now accounts for 16% of all vehicle sales.

High-profile customers include Eric Clapton, who spent £3m on a one-off bespoke Ferrari, and Michael Stoschek, a German car enthusiast, who is thought to have spent even more on developing a single modern descendant of the Lancia Stratos rally car.

Has austerity changed things? No. The latest generation of recession-busting hypercars is likely to drive the extravagance even further. McLaren's new P1 supercar is due out next year with a price tag of about £800,000. Fux won't be among those looking through the options list in McLaren's catalogue. Instead, he'll decide what specification he wants - perhaps one to match his favourite raspberry shirt - and order it direct from the Woking factory.

Earlier this year McLaren unveiled its X-1, a one-off car designed for a mystery client by its special operations division, set up to meet the rising demand for this kind of bespoke work.

The car is so different from any other model that it had its own road test programme. McLaren said that it created a mood book for the customer, which included "inspiring images from which the design spirit of this unique car would be derived". The images included classic cars, but there were also pages with an Airstream caravan, a Montblanc pen, a grand piano, Audrey Hepburn in black and white ... and an aubergine. "The client liked the shiny texture of the finish," said Frank Stephenson, the design director.

Pimping cars for the stars is a bandwagon that all high-end manufacturers are keen to climb aboard. Gavin Hartley, head of bespoke design at Rolls-Royce, says he has more than 1,000 buyers a year who personalise their cars. The modifications are made on the production line. There are now six designers in his department, up from two 18 months ago, and 90% of Phantom saloons are sold with bespoke work. Six years ago it was 50%.

It's good news for Rolls-Royce’s finances, although the company is loath to say exactly how much customers typically spend. "You could be budgeting 30-40% on top of the cost of the [£276,000] car in broad terms," says Hartley. "The vulgarity of cost we try to avoid, really."

Tailoring the car is "entertainment and fun" for clients, he declares. Some of the more garish choices have involved alligator leather trim, initialled headrests and big-screen televisions in the back. He once designed a car apparently suited for the most expensive teddy bears' picnic in the world.

"There was a customer from the Middle East who came to us some time ago," says Hartley. "It was a Drophead coupe with a tartan boot trim. We did a walking stick, bespoke Thermos flasks and a binoculars holder. We supplied the customer with fitted luggage, a picnic hamper and a bag for his wellington boots, even."

The typical customer doesn't care whether their car is seen as tasteful or not, says Hartley. "They are not really bothered about what the next person thinks," he says. "They are doing it for personal reasons."

Bespoke work is becoming a moneyspinner even for the makers of cars previously renowned for their practicality. Buyers of the new Range Rover will be offered more personalisation options than ever before, including any colour scheme under the sun - at a cost - and 22in wheels, a popular after-market addition to the outgoing model.

"If after-market companies are doing something, then we want to do it properly," says Nick Rogers, director of Range Rover programmes. "It makes sense if we can offer more of the features that customers want."

BMW's Individual service has also seen more customers wanting features such as gold buttons, salmon-skin leather, inlaid flower designs studded with Swarovski crystals and leather dog baskets. One owner wanted wood trim from a tree that had been growing in their estate. Franca Sozzani, the editor of Italian Vogue, commissioned a 7-series saloon with a small bookcase between the rear seats, so that her magazines wouldn't slide around.

Mercedes has produced cars with an interior to match a shade of lipstick, and pink Bentleys are a favourite of Paris Hilton and footballers' wives.

Perhaps the ultimate guarantee of a bespoke car is when the manufacturer includes in the price the tools that were used to build it, thus ensuring that other wealthy customers can't own an identical car. Such was the case with Clapton’s Ferrari. He took delivery of his one-off SP12 EC model in May. It is based on the current 458 Italia coupe, but with a new body inspired by Clapton's favourite Ferrari, the 512 BB from the 1970s.

Eric Clapton with his £3m one-off Ferrari SP12 EC

He has spoken about the car only once, telling the official Ferrari magazine it was "one of the most satisfying things I've ever done".

But while these one-off cars solve some problems experienced by tycoons, they can create a new one. "I'll think about what car I'm going to drive the day before," says Fux. "It can be a difficult decision."

Foam and fortune: the baron of bespoke

Michael Fux, a 69-year-old multi-millionaire, made his fortune from selling memory foam mattresses and pillows. His rags-to-riches story began when he and his family emigrated to America from Cuba in 1958. He worked his way up the sales ladder at department stores before spotting an opportunity in bedding.

Nine years after founding Sleep Innovations in 1996, Fux (pronounced "fewks") was riding high with annual sales of £220m. His company was bought by a private equity firm and though the price was never disclosed it gave Fux enough cash to start another memory foam company - and to create one of the world's most expensive car collections.

"When it comes to Aston, Ferrari, Rolls-Royce and McLaren, they will do all kinds of things," says Fux. "You've gotta be willing to pay for it, but you can get whatever you want."

This claim is backed up by his fleet of 125 cars, most tailored to his specification. There are seven Ferrari F430 sports cars in different colours; a pale green Ferrari 458 Spider with matching pale green interior; and several Phantom Dropheads including one in cherry red with a carbon fibre trim inside.

"I like the idea that a car will last for many, many years," says Fux. "I try to envisage a car 50, 100 years from now and for people to look at that car and think, "Wow that's something really special."

"The cost could run anywhere from £100,000 to £300,000. At Rolls-Royce, I tell them what I want and we don't discuss price until the car is built."

Data and Money and Transport

-