Collecting Articles

1. Dolls Houses

2. What To Put Away For 2030

3. Jukeboxes

4. PanAm First Class Cabin

5. Eggers

6. Hoarder's Brain

7. Obsessives

8. Spitfires In Burma

9. Red Boxes

10. Tanks

11. Iceland's Penis Museum

12. Vinyl

13. Wine Forgeries

14. Plane Spotters

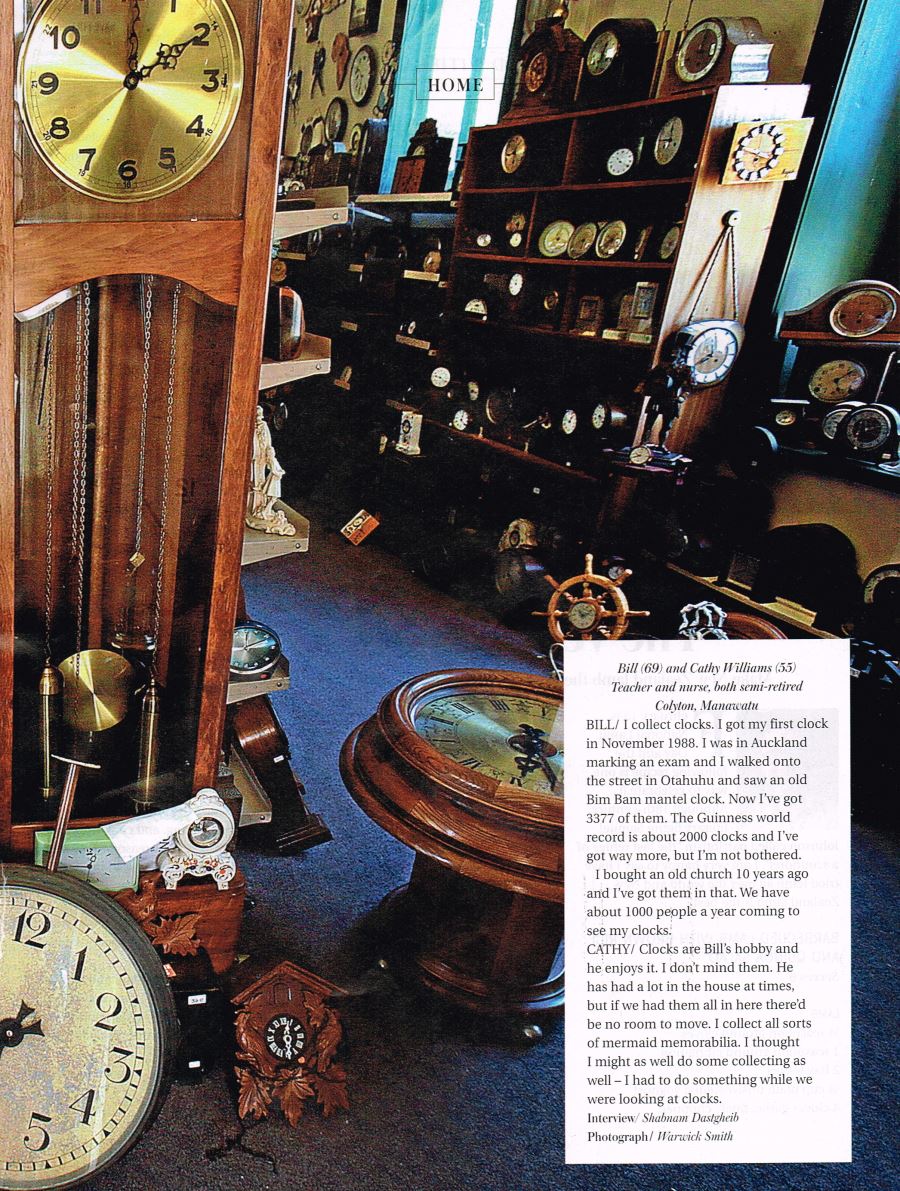

15. Clock Man

16. $1000 LPs

17. Model Railways R Rated

18. All The Top 40 Records

19. 15 Collectibles That Are Completely Worthless>

20. Crowd Sourcing Old Airfix Models

21. Rod Stewart's Model Trains

22. The Pez Outlaw

23. Cereal Box Collectors

24. Trash Museum NY

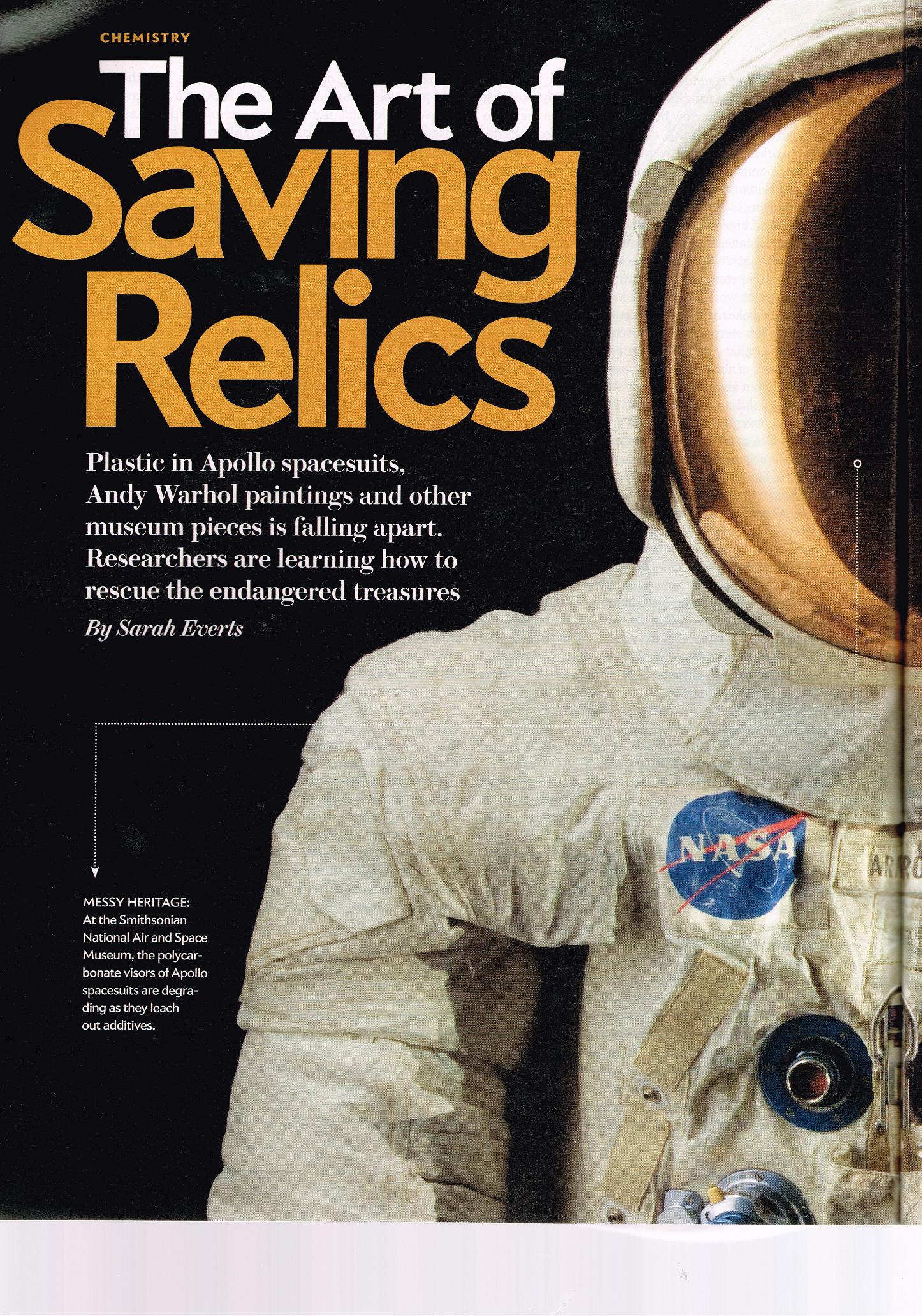

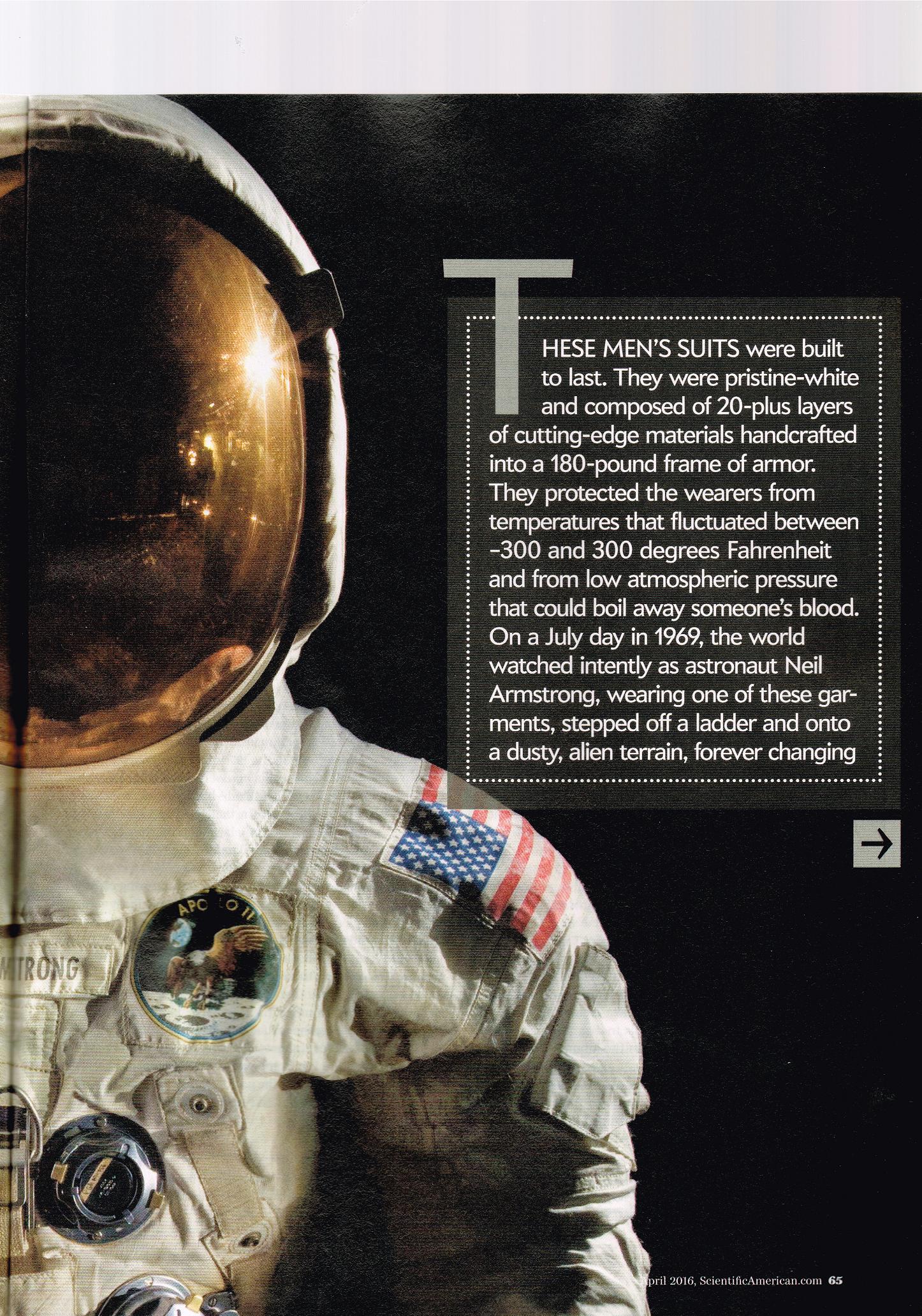

25. Conservation of Relics

26. Guy collecting his name - Glen Eden

2. What To Put Away For 2030

3. Jukeboxes

4. PanAm First Class Cabin

5. Eggers

6. Hoarder's Brain

7. Obsessives

8. Spitfires In Burma

9. Red Boxes

10. Tanks

11. Iceland's Penis Museum

12. Vinyl

13. Wine Forgeries

14. Plane Spotters

15. Clock Man

16. $1000 LPs

17. Model Railways R Rated

18. All The Top 40 Records

19. 15 Collectibles That Are Completely Worthless>

20. Crowd Sourcing Old Airfix Models

21. Rod Stewart's Model Trains

22. The Pez Outlaw

23. Cereal Box Collectors

24. Trash Museum NY

25. Conservation of Relics

26. Guy collecting his name - Glen Eden

Dolls Houses

-

Rubber gloves! Beautiful. I've been looking for a pair of these for nearly two years. Penny Whitehouse hasn't just spotted a pair of marigolds - these rubber gloves are exactly an inch long. I've found others that come close to being right, but they're always too bulky. Rubber is thick and hard to shape so getting the fingers this delicate is really hard.

Every year over 3,000 collectors flock to the Kensington Dolls House Festival to adorn their dolls' houses with miniature books, chandeliers, wheelbarrows, ordinance survey maps, cabbages, brandy, monopoly sets and just about anything else you can think of, in miniature. And there isn't a child in sight. In the sea of blue-rinsed pensioners, the youngest collector in the room is probably pushing 50.

Next to a stall selling tiny pseudo-Victorian portraits is a stall selling miniature copies of Hello magazine for £7.50 and miniature pots of Vaseline. After a special request, Platts Mini Packages started selling tiny packets of sliced bread: I already sell non-sliced, but this customer wanted sliced, said stall owner Liza Lawrence. It is hard to see what difference a single word on the outside of the 1cm high packet of 'Hovis' could possibly make, considering it's stuffed with toilet roll anyway, but miniature collectors like perfection.

It's all about control, says Charlotte Stokoe, organiser of this year's Kensington Dolls House Exhibition. It's about a house with no dirty dishes, that you can control completely, with no kids to mess it up. It's really appealing to a lot of people.

The Kensington Dolls House Festival, which was held on the 16th, 17th and 18th of May this year, is celebrating its 25th birthday and claims to be the most high profile exhibition of its nature in Europe. The festival takes place in Kensington Town Hall because, as the brochure says, it is a civilised venue with "decent loos".

The idea of perfection dominates each tiny product at the exhibition. Pointing to a tiny Victorian portrait, the stall holder assures customers it has been hand painted on vellum. What is vellum? The skin of an unborn calf comes the answer.

Terry Neville started selling miniature books four years ago when he realised there was a healthy market. His trademark is that each book actually contains all, or a healthy chunk, of the actual text.Recently his company managed to get copyright to reprint the full set of Ian Fleming James Bond novels, 1/12th of the actual scale.Do they sell?

Yes: but not as well as Bibles. The miniature Bibles each contain 17 chapters of Revelations. Revelations was chosen because the market is primarily interested in the hell fire and damnation aspect of their miniature Bibles, says Neville.Each small book is cut by hand, stitched, and takes about two days to make. Dateman books sells over 200 titles and has been experimenting with producing books in 1/24th scale. Although there is a demand, the 1cm high books, each with real pages, have too high a failure rate to be profitable.

There is even a market for 1 inch high Bibles in French. One copy was recently returned to Mr. Neville for having the accents in the wrong place. The collector had been reading, for leisure, the 1mm high characters.

John Hodgson, who has been in the business for 30 years, says dolls' house collecting isn't all about kitchens and bathrooms. A German lady once asked if he sold miniature torture instruments, presumably to furnish her dolls' house dungeon.

Acquiring the tools of espionage for your dolls' house is not as hard as you might imagine. Put a secret drawer in a piece of furniture and it will sell. "If the customer is undecided - you've shown them the diamond glasses and the tortoise shell lid and they're still not sure - you just pop open the secret drawer and they'll take it," says John Hodgson, whose Dutch tea caddy complete with a hidden pop-out drawer retails at around £500.

Collecting miniatures is not cheap. Mr Hodgson's four poster bed, circa 1770 but about the size of a shoebox, will sell for £675. Mr Hodgson describes his American collectors as like children with money. The general feeling is that sales and customers have increased this year. Along with thermos flasks and British holidays, collecting miniatures is yet another hobby that looks like it could be thriving in the recession.As one collector tells me: "I can't afford a house in Tuscany or a medieval castle in real life, so I buy them in miniature. It's a total, total substitute.

But that doesn't explain the motives of The Sultan. The Sultan is a legend amongst those who sell miniatures. There are whispers of him over by the tiny flower pots (1cm high, £2.50) and the meat carcasses (6cm long, looks vaguely like a cow, £14). Simon Walker sells tiny things made of silver and explains: "He walks through the stalls with his entourage and just points at things he wants - and the minions just buy them for him." Mr Walker must be secretly hoping that The Sultan will walk past his stall and point at his prized product, a miniature silver car costing £4,500.

John Hodgson knows more about The Sultan. Rumour has it he is a very wealthy royal from Qatar who is "quiet, kind and reserved" and turns up at exhibitions with suitcases full of money. The Sultan, although an avid miniatures collector, doesn't seem to have made an appearance today.

Facts about Dolls' Houses:- The earliest known miniature houses are nearly 5000 years old and were found in Egyptian tombs - Dolls' house collectors in England use two scales: 1/12th and 1/24th. The former is more popular.- One of the most famous dolls houses is Queen Mary's dolls house which was built in 1924 and is on display at Windsor Castle - Judy Dench is a known collector - For information about the Kensington Dolls House Christmas Show go to www.dollshousefestival.com

An $8.5 million dollshouse

What To Put Away For 2030

-

Ten collectibles of 2030

Alternative investments are especially attractive when stock markets are in turmoil. So Times Money asked five antiques experts to name their best bets for collectibles of the future. We wanted contemporary items that could be bought online or in mainstream shops for £100 or less and should increase in value - hopefully significantly - by 2030. Their tips are supplemented by our own choice and by two suggestions from Christie's for bigger spenders. To realise the best price in a future sale, all items should be kept in original condition, with all packaging. Note that predicted prices are in today's terms and do not take inflation into account.

"I'm not a plastic bag" by Anya Hindmarch

Anita Manning, Great Western Auctions

Expert on Bargain Hunt (BBC) and Flog It! (BBC)

We should look for something which will reflect our present day world, is well designed, made in limited editions and, if possible, of some quality. Anya Hindmarch's "I'm not a plastic bag" re-usable canvas tote is my bet for a collectible of the future. It reflects our present day concern for climate change and preserving the resources of our planet. These bags were made in limited editions of four colours and sold new at Sainsbury's for just £5. They are already changing hands on eBay for eight times that. Anya Hindmarch is one of our leading designers, and the bags were not only topical but gave people a chance to buy a designer piece which would otherwise be out of their reach. By 2030 I predict that these will become collectors' pieces and change hands for at least £500. Condition is all important, so store carefully.

Times Money adds: The bag is no longer available from Sainsbury's. Examples in original condition can, however, be had on eBay for around £20 to £30.

The mobile phone

Philip Serrell, Philip Serrell Auctioneers & Valuers

Expert on Bargain Hunt and Flog It!

Think of one possession that most of us have at least one of. Sometimes these gems of modern day technology are given to us and we pay for the privilege of using them. In my view the mobile phone has revolutionised our lives and will become collectable in the way that phone cards have. But make sure you keep all the accessories, including the packaging (and the thing that fits in the ear that makes one look like a night club bouncer). Surely the front runner will be the Del Boy brick. Value in thirty years time? Who knows but in today's terms my guess is £100 or more.

Times Money adds: Carphone Warehouse sells a vast range of handsets. Retrobrick deals in classic mobiles, including the Motorola DynaTAC 8500x used by Derek Trotter at £59.

The celebrity autograph

Philip Serrell

Alternatively, my £100 could be spent travelling to rock concerts, film premieres and sporting events to collect autographs. The four Beatles signatures from the early 60s are now worth thousands. Sadly as time passes and our heroes pass with it, the value of their signatures can only increase. I think I would have to try to persuade young racing driver Lewis Hamilton to sign my small book. Value in the future? Well there is the gamble, but if our Lewis wins Championship after Championship and, perhaps, becomes very reclusive, then his mark could well be worth as much as £500 by the year 2030.

Times Money adds: Autograph Magazine has some interesting features on "philography" here.

David Linley gifts

Philip Serrell

The trouble with choosing a collectible of tomorrow is one needs the ability to predict fashion changes. Will Beckham Fragrances aftershave (from £15) - complete in its carton - become collectable? Who will be the next Banksy and turn graffiti into gold? For my third choice, I would log on to the website of David Linley, furniture maker and the Queen's nephew. There I would probably go for either the set of 10 cased pencils at £15 or a rosewood bookmark shaped as a paperclip at £19, all stamped Linley. This investment would have it all - a royal connection linked to a sought after designer name. How could it fail to be worth £100 or more in thirty years' time? Provided of course I hadn't sharpened my pencils. Times Money adds: Another affordable item with a Royal Connection is this £45 gardener's gift set from the Prince of Wales' Duchy Originals range, with a hand trowel, hand fork and wooden box-cum-planter.

Children's books

Kate Bliss, independent fine art valuer

Expert on Bargain Hunt and Flog It!

It is no secret that collectibles in mint condition are the most desirable and expensive. Mint collectible children's books are rare - most have been loved and enjoyed repeatedly and bear the scars. I particularly love children's pop-up books, not only the most vulnerable to damage but a world of discovery for toddlers meeting books for the first time. I remember as a child Haunted House by Jan Pienkowski, a pop-up book published in the 1970s and 80s, that has already become a collector's item. I think the classics such as Eric Hill's Spot books and Rod Campbell's Dear Zoo available in bookshops today for as little as £4.99 will be worth collecting for the future. By 2030, a mint example may be worth three or four times its price and should continue to rise in value. My tip is buy two copies and keep one away from sticky fingers!

Times Money adds: Amazon.co.uk has a huge selection.

The mouse mat

Elizabeth Talbot, Diss Auction Rooms

Expert on Bargain Hunt and Flog It!

My nomination for an affordable contemporary item that should increase in value is the humble mouse mat. They are a creation specifically for the current age, have no predecessor and will be made redundant by swiftly developing technology in the very near future. Therefore, although mass-produced, we already know there will not be an infinite supply. Being a piece of equipment, bought to be pressed into service, most mouse mats are ripped out of their packaging without a second thought being paid to it. Therefore, a mouse mat in original packaging or original condition will be a rare find in 22 years time. I believe a new mat currently costing £5 to 20 with any of the desirable characteristics sought by a collector may well sell-on for £50 to £100-plus in 2030.

Times Money adds: Google "mouse pad" as well as "mouse mat" if shopping online. Interesting options include Mouse Rugs and the London Transport Museum's Underground map mats.

Something craft-y

David Harper

Expert on Bargain Hunt

Avoid anything that is readily available in every department or furniture store in the land. What you are looking for is rarity, individualism and something made by hand by a craftsman. So, the trick is to find a talented potter, painter or sculptor either locally or through the internet - someone who's work you like and will enjoy owning. Buy it from them direct, make sure you keep the receipt with the item and even better get the artist to sign a letter of authenticity and if you can, have your picture taken with them! It all sounds a bit cheeky, but if they drop dead in ten years time and turn into an Andy Warhol, you will be quids in.

Times Money adds: The Crafts Council can help you to find a suitable maker.

For bigger spenders

According to experts at Christie's, two wines that should make a good investment are:

Chateau Mouton Rothschild 2000 - now £500 a bottle at The Antique Wine Company

Chateau Lafite Rothschild 2000 - now £1,295 a bottle at Berry Bros. & Rudd

Note also: "The 2005 vintage wines will start to be traded in the auction market in 2008, and I expect that the top wines from this vintage will increase in value, as it is a superb vintage, possibly as good as 1961."

If wine does not appeal, Christie's tips "cutting-edge" gadgets, such as the Apple iPod and iPhone.

"Whether we'll sell this sort of thing by 2030 remains to be seen, but the consensus is that they could potentially be of interest."

The compiler's choice

A browse of Abebooks.com shows that signed first edition books by popular authors can rocket in value. Hatchard's, of Piccadilly, always has a good selection, many for under £20. One good bet for 2030 could be The Reaver, the last novel of George Macdonald Fraser, author of the Flashman novels, who died on January 2. This costs £18.99. As an example of investment potential, a signed first edition of Spike Milligan's Robin Hood I bought new for £10.99 in 1998 now fetches around £300 in as-new condition.

Jukeboxes

-

They've been through hell together and the parties were great

I bought my jukebox, a 1974 Wurlitzer Americana 3800, in the spring of 1999. She holds 200 7in singles, gives off the purple glow of a fading radioactive sunset, hums like a 1950s refrigerator and reminds you what records were supposed to sound like - not thin and compressed into machine computer code, but vast, warm and with lots of legroom. But in the age of the iPod, when a sleek unit smaller than a cigarette pack can store literally thousands of songs, what can possibly be the attraction of owning a kennel-sized metal box full of scratched vinyl, uniquely unportable and with a volume control that you need a screwdriver to operate? And, at this special time of year, for anyone considering making an impulsive Christmas purchase - as we have been encouraged to do by manufacturers - what are the pros and cons of investing in such a cumbersome antique?

Today, in pubs and bars, the jukebox stuffed with a few dozen scratched 7in singles advertised by a crudely handwritten playlist has been replaced by a compact, brightly lit unit crammed with CDs offering thousands of instantaneous entertainment choices. Or else it's a curious novelty item, flagged as one of the attractions of a desperately fashionable hang-out: German beers. Italian sausages. Original 1950s jukebox.

Or, worse still, the vintage jukebox has been stolen from the public it was built to serve, and squirreled away in the corner of a room by a selfish middle-aged music fan, whose semi-autistic, fetishistic approach to the object bears no immediate relation to the innocence with which the machine would once have been enjoyed by happy-go-lucky teenagers. Me, in other words.

When I bought my jukebox, I had just co-written a well-received television series that I had no reason to assume would be cancelled immediately. I wrongly imagined I could easily afford the £1,000 price tag Juke Box Services of Twickenham, who heroically recondition old jukeboxes, had attached to the Wurlitzer. I reasoned that I might soon even have a flat of my own to keep it in. Three months later, work had dried up, and my unjustifiably self-indulgent purchase was finally delivered to a second-floor, northeast London maisonette, where three men struggled to stuff her through a doorway ultimately too narrow to accommodate her. The Wurlitzer went back to Twickenham for a few weeks.I measured my window frames and booked a hydraulic lift, an expense I could suddenly no longer really afford. A decade later, I really should have double-glazed this flat, but one day Wurlitzer will need to exit through the same window by which she once entered, so we shiver, but while we shiver, we are listening to the aching bass part of the Byrds' Hey, Mr Tambourine Man as it was meant to be heard.

The first lesson of jukebox ownership is this. Never buy anything bigger than your house.The physical bulk of the purchase dealt with, there is then the issue of what to stock the jukebox with. I bought the Americana 3800 because she held the most 7-inches, but I soon realised that I was about to begin wrestling with the terrible dilemma of what, exactly, would be my 200 favourite singles of all time.

Nick Hornby has made a literary career out of anatomising this curiously male desire to arrive at ultimate lists of definite best-ofs, be they musical or sporting. And stocking a juke-box gives a man a way of setting in stone, or at least in little slots on a rotating platform, the physical evidence of his long-apprenticed professorship in good taste.I gathered up all the singles I had bought throughout my life, and scoured the internet, second-hand shops and record fairs to plug the gaps in the wants list I had scrupulously drawn up. I imagined visitors prostrate in admiration at my immaculate selection, which would have cherry-picked the finest moments from every era of popular music, while still including enough rarities and obscurities perhaps to expand my guests' inevitably narrow horizons a little as well, to make them realise how much better informed - and how much better a person - I was than them.

The procedure was fun. The website www.gemm.com was a gold-mine of cheap 7-inches, and I still remember the moments when some sought- after items presented themselves in the flesh. Barbara Ray's heart-rending country and western weepy I Don't Wanna Play House leapt out of the rack of a charity shop somewhere in the Western Australian desert; the Tenors' early reggae classic Ride Yu Donkey revealed itself, unexpectedly, on a stall in Spitalfields Market; a four-track EP by Cannonball Adderley and Nancy Wilson arrived in the post in an unexpectedly beautiful picture sleeve.

In the end, the Wurlitzer kind of stocked herself. Anything recorded much after the early 1980s sounded too thin and clattering in her vast speaker cabinets. She preferred the warm fuzz of vintage psychedelia and the Cuban-heeled stamp of the 1960s beat boom, the joyful stomp of vintage soul floor-fillers and the scratchy minimalism of 1970s punk; the booming basslines of 1950s Chicago blues and the plangent laments of country singers.

The Wurlitzer is a high-maintenance mistress. I scour the internet for replacement styluses and, on more than one occasion, the engineer from Juke Box Services has had to be cajoled into making a long journey north. But I am grateful to the Wurlitzer because she cured me of musical pretension, or at least staved it off for a few seasons. I was 30 years old, a die-hard music fan and even a semi-professional critic, drawn ever further away from the three- minute pop songs that first captured my imagination into worlds of free jazz and post-rock and white noise. The Wurlitzer reminded me of the irrepressible power of the perfect 7in. And with a flat stuffed with revellers, she made a succession of New Years' Eves in the early Noughties swing in a way that poring over a box set of Albert Ayler albums probably wouldn't have done. I remain eternally delighted by my expensive mistake. But remember. A jukebox is not just for Christmas.

PanAm First Class Cabin

-

Man Spends $50,000 to Recreate a First-Class Pan Am Cabin in His Garage

Anthony Toth is so obsessed with perfectly recreating a vintage Pan Am first-class cabin in his garage that he once traveled to Thailand for - wait for it - original Pan Am branded headphones. And his obsession goes much deeper than that.

Anthony began his obsession with Pan Am as a child, when he and his parents frequently flew to Europe to visit family. Pan Am's service seems decadent and almost silly today, when Southwest and JetBlue achieve success with a budget mentality, but to Anthony, Pan Am was the epitome of class and style.

Pan Am was once synonymous with international jet-setting, with upper-deck dining rooms and flight attendants decked out in crisp blue uniforms, high heels and white gloves. First-class travelers were served out of silver-plated martini pitchers. A parade of linen-covered food carts made its way down the aisle at dinnertime.

Anthony saved things like the cardboard linings on food trays and recorded his trips with multiple rolls of film and extensive tape recordings of the radio selection on board. "This consumed my world," said Tosh. As an adult, he works for United Airlines, and two years ago bought a home with an oversized garage in which he could build a faithful replica of Pan Am's first-class cabin. The project has taken him, in total, 20 years.

Construction required multiple visits out to a spot in Death Valley where airplane carcasses are dumped, but the details of his project are unnervingly precise: The replica isn't open to the public, but if you visit (Tosh hosts executive meetings sometimes, appropriately enough), you'll be offered drink service and given a perfectly-crafted souvenir boarding pass designed to match those used by the airline in the late '70s and early '80s. He's got authentic Pan Am swizzle sticks and glasses. The overhead compartments are original Pan Am construction. Hell, he's even got sealed packages of salted almonds (we have no evidence regarding the taste of 30-year-old almonds, but they're probably not for eating anyway).

The one concession he's made to the modern age? A flat-screen TV in place of the old-school projection Pan Am used. Everything else (save the stewardesses) is either original Pan Am or a custom-made replica. He's hoping to open his obsessive ode to Pan Am as a museum, but he seems perfectly content to just hang out in first class.

Obsessive Collectors - Eggers

-

Make-believe world of jailed egg thief, Richard Pearson

At 7.30am one autumn day in 2006 nine police officers arrived outside a semi-detatched house on a quiet suburban street in Cleethorpes.

Richard Pearson, 41, a painter and decorator, opened the door. His wife had gone to work; he called her to come home and take care of their six-month-old baby. There followed what one of the search team described as an interesting bit of dialogue between the two: she knew he was going to jail.

Pearson was jailed for five months at Skegness Magistrates' Court this week. PC Nigel Lound, from Lincolnshire Police, who led the search team, said: He was a pleasant chap, worked hard, family man. He just spent his weekends decimating our wild bird populations. He had become completely obsessive about collecting eggs.

Pearson led police to a back bedroom where, stacked in fish crates, biscuit tins and a suitcase, were more than 7,000 birds' eggs. There was a large sheaf of papers, photocopies of diaries that the police and the RSPB had never seen before.

They were the egg-hunting memoirs of Britain's most notorious egg collector, Colin Watson, who died in 2006 after falling out of a larch tree. The diaries, written in exercise books with dates encoded, were evidence of Pearson's links with Britain's strange and secretive society of eggers.

Guy Sharrock, a senior investigations officer at the RSPB, broke the code and spent a week reading and cataloguing the contents. They provided details of previously unsolved nest robberies. They also provided an insight into the minds of men who crawl up trees and down cliff faces, risking their lives in pursuit of prizes with no monetary value that can never be displayed in their homes for fear of a police raid.

They are always men. Mr Sharrock has seen doctors, dentists and police officers - he knows two conservation workers with spent convictions for collecting and an eccentric Norfolk millionaire - but for all that there is a strong trend for egg thieves to be working-class men who began collecting as children, following the example of a relative or a friend.

Gregory Wheal, a roofer, who has recently broken Watson's record with a ninth conviction for egg collecting, followed his father into the habit. He works for another convicted egg collector and lives in the egg-collecting capital of Britain, a suburban corner of north Coventry beside the M6.

Eggers frequently carry the journals of Victorian collectors, harking back to a time when raiding nests was considered a respectable pastime for ornithologists, yet they often appear to enjoy the challenges that the modern egg collector faces.

It's not just about taking eggs, Mr Sharrock said. It's about beating the police, beating the RSPB, beating the system.

Watson closed a rather typical diary entry with: It was now 04.30 and coming light so we called off the mission. He described car chases with the police, throwing freshly stolen osprey eggs out of the window. One of his associates told Mr Sharrock how, as police approached his car, his colleague had eaten a clutch of rare wader eggs to destroy the evidence.

The idea that stealing birds' eggs is comparable to the exploits of secret agents seems present in the letters of the Liverpool egg collectors, among them Carlton D'Cruze. When police and the RSPB raided his home, to find him kneeling in the bathroom, attempting to crush his collection and feed it into the lavatory, they found correspondence between collectors who were represented by numbers.

Mark Thomas, the RSPB inspector involved, said: They would write: 'From No 2 to No 5.' They would sign off saying: 'Destroy this after reading.'

Mr Thomas rolled his eyes. The letters were in a file marked 'Top Secret', he said.

The fever to collect mounts among the eggers as the breeding season approaches. When it begins they will be away every weekend. Information for the authorities' operations to catch the culprits often comes from wives tired of seeing their partners disappear for days on end.

It's all about trophies, Mr Sharrock said. The eggs are the trophies of their exploits in the field. Colin Watson would say: 'I can look at my clutch of golden eagle eggs and I can remember everything'.

Brain Scans of Hoarders Reveal Why They Never De-Clutter

-

Jill, a 60-year-old woman in Milwaukee, has overcome extreme poverty. So, now that she has enough money to put food in the fridge, she fills it. She also fills her freezer, her cupboard and every other corner of her home. “I use duct tape to close the freezer door sometimes when I’ve got too many things in there,” she told A&E’s Hoarders. Film footage of her kitchen shows a cat scrambling over a rotten grapefruit; her counters—and most surfaces in her home—seemed to be covered with several inches of clutter and spoiled food. “I was horrified,” her younger sister said after visiting Jill. And the landlord threatened eviction because the living conditions became unsafe.

Jill joins many others who have been outed on reality TV as a “hoarder.” We might have once called people with these tendencies “collectors” or “eccentrics.” But in recent years, psychiatrists had suggested they have a specific type of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A movement is underfoot, however, for the new edition of the psychiatric field’s diagnostic bible (the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5), to move hoarding disorder to its own class of illness. And findings from a new brain scan study, published online August 6 in Archives of General Psychiatry, support this new categorization.

Hoarding disorder is categorized as “the excessive acquisition of and inability to discard objects, resulting in debilitating clutter,” wrote the researchers behind the new study, led by Yale University School of Medicine’s David Tolin.

Many of us might feel our homes or workspaces are far more cluttered than we would like—or than might be good for our peace of mind. But those with diagnosed hoarding disorder usually have taken this behavior to a different level. The Mayo Clinic even has a guide for treatment and prevention of hoarding disorder. One recommendation they provide: “Try to keep up personal hygiene and bathing. If you have possessions piled in your tub or shower, resolve to move them so that you can bathe.”

Some people hoard particular types of things, such as newspapers, craft supplies or clothing. Others, with a condition known as Diogenes syndrome, keep trash, including old containers, rotting food or human waste. Finally, as Animal Planet’s Animal Hoarders has shown, many hoarders collect more pets than they can appropriately care for, risking both their own and their animals’ health and safety.

To find out more about how the brains of hoarders might actually differ from those of healthy adults—and potentially even those with OCD—Tolin and his colleagues recruited 43 adults with a diagnosed hoarding disorder, 31 with OCD and 33 healthy adult controls to undergo fMRI brain scans. Each subject was asked to bring in a stack of miscellaneous, unsorted papers from their home, such as newspaper and junk mail. A similar collection of paper items from the experimenters was intermingled. Fifty items belonging to the subject and 50 items belonging to the experimenter were scanned and projected into the subject’s field of view in the fMRI. Subjects were asked to choose whether they wanted to keep a displayed item (either belonging to the subject or to the experimenters) or get rid of it by pressing a button. Afterward (and in a shorter pre-experiment training session), all of the discarded items were shredded right in front of them—ensuring that they knew that their decisions would have a real and immediate consequence.

Healthy controls chose to discard a mean of about 40 of the 50 items they brought. Those with OCD discarded about 37 items. But those with a hoarding disorder discarded only about 29 of the 50 things they brought. It also took hoarders slightly longer than healthy controls (2.8 seconds compared with 2.3 seconds) to make their decision about what to do with the items. And they reported substantially more anxiety, indecisiveness and sadness than healthy controls or those with OCD while making decisions.

Those with hoarding disorder showed key differences in the fMRI readings in both the anterior cingulate cortex, associated with detecting mistakes during uncertain conditions, and the mid- to anterior insula, linked to risk assessment, importance of stimuli and emotional decisions.

Interestingly, hoarders showed lower brain activity in these regions when they were deciding about other people’s items. But when they were faced with their own items, these areas of the brain showed much higher rates of signaling than those in either people with OCD or the healthy controls. Those with hoarding disorder also reported “greater anxiety, indecisiveness and sadness” during the decision-making process than those with OCD or the healthy controls.

As Tolin and his co-authors noted, hoarders are not necessarily eager to keep everything they possess, but rather “the disorder is characterized by a marked avoidance of decision-making about possessions.” And the extra activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula while evaluating what to do with their own items “may hamper the decision-making process by leading to a greater sense of outcome uncertainty,” the researchers noted. In other words, hoarders might often feel that they are at risk of making a wrong decision—and that that decision could bring with it greater risk than it actually would. “The slower decision-making may be a central feature of impaired decision making in hoarding,” the researchers noted.

The frequent theme on hoarder reality shows is that the individual does not realize that their lifestyle has spiraled out of control. Bernie, a 59-year-old Illinois woman featured on TLC’s Truth Be Told: I’m a Hoarder said, “I don’t consider myself to be a hoarder—not at all,” even after showing the film crew an entirely full house and a pool table room piled nearly to the ceiling with toys and other collected items—and after her daughter and son had implored her to clean up her house. As the authors of the new paper note, those with the disorder “are frequently characterized by poor insight about the severity of their condition, leading to resistance of attempts by others to intervene.” And as the Mayo Clinic notes, even if hoarders’ collections are disassembled, they often begin acquiring more items right away because their underlying condition has not been addressed.

As with for patients with OCD, those with hoarding disorder have had some success reducing negative symptoms by taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are also frequently employed to help patients overcome the disorder. Although neither of these approaches is a sure-fire way to cure hoarding, the biggest hurdle to recovery still seems to be recognizing the problem. And as the Mayo Clinic recommends, “getting treatment at the first sign of a problem may help prevent hoarding from becoming severe.”

Obsessives

-

Men who collect multiple copies of same album

(story begins bottom right corner "It's a Numbers Game")

Spitfires In Burma

-

If these Spitfires are where David Cundall thinks they are, in the condition that he claims they are, he may be selling his discovery short.

Original Spitfires are now so precious that collectors would consider £1.5 million per plane — the upper end of Mr Cundall’s price range — an extraordinary bargain. “£2.5 million to £2.8 million and up would be closer to the mark,” one expert told The Times last night.

Seventy years after their glory days, airworthy Spitfires fall into three categories: fully preserved specimens such as those flown by the RAF’s Battle of Britain Memorial Flight; reconditioned planes, which need only an original nameplate to qualify as authentic, however extensively they have been rebuilt with new parts; and replicas, which sometimes don’t include a single original component.

The Cundall Spitfires, allegedly still wrapped in their original Castle Bromwich tar paper, would be the Second World War aircraft devotee’s equivalent of mint Penny Blacks.

There is still scepticism that the Burmese find will yield as many as 20 complete aircraft. There is also the possibility that, if it does, it might lower prices by flooding the market. But few doubt Mr Cundall’s bona fides as a Spitfire hunter, nor the significance of the evidence so far revealed by his ground-penetrating radar.

These Mark XIVs were among the fastest Spitfires ever built. Their Rolls-Royce Griffon engines packed roughly twice the punch of the first Merlin engines used in earlier models (and twice as many horsepower as a modern Bugatti Veyron).

They were normally flown away from the mighty Castle Bromwich plant rather than being crated and loaded on to ships, meaning those buried in Burma have, in car sales parlance, yet to be driven off the forecourt.

It is no small irony that soon after Whitehall decided not to pay to remove the aircraft from Burma, the Burmese and other Asian governments started buying second-hand Spitfires to equip their rudimentary post-war air forces — and British Spitfire pilots took to the skies again to deliver them.

Red Boxes

-

For departing politicians, it is the ultimate souvenir of their time in the limelight. More than 40 former ministers have paid almost £1,000 each for red ministerial boxes since 2010.

Anyone who has held a ministerial post can buy the distinctive briefcases, which are embossed with their owner’s name and title in gold leaf. A Whitehall source said the practice, which has been going on since the early 1990s, is partly designed to stop the boxes mysteriously disappearing. “There have been very, very naughty instances of boxes going for a walk — usually around election time,” the source said.

Figures released under the Freedom of Information Act show that since 2010, seven former ministers in the Foreign Office and Departments of Education and Justice have bought their old boxes. In addition, Barrow & Gale, the London-based manufacturer established in 1750 which makes the briefcases, said that up to 35 others had bought them from it directly, but would not say who or how much they paid.

Dawn Primarolo, who served as Children’s Minister in the previous Labour Government, said that she had decided to buy her box to mark “an incredibly important part of my life”. She bought the briefcase for £850 and said that she thought it was something she could show to her grandchildren. “It’s just a nice box that sits on the bookshelf in my workplace,” she added. “It’s a keepsake for me, just a memento. You can’t use them every day, not unless you want to break your back. They weigh a lot and they’re not very practical.”

Others are more reluctant to reveal whether they have held on to one as a reminder of former glories.

Although the red box is most closely associated with the Treasury, Alistair Darling, the former Chancellor, said that he hadn’t bought one. His predecessor, Gordon Brown, and Ed Balls, the Shadow Chancellor, couldn’t be reached for comment.

Barrow & Gale is a discreet London-based leather goods company which was established in 1750. The boxes, which weigh up to 3kg, take three days to make. Beneath the red-stained rams’ leather the briefcases are constructed with pine grown in a cold climate to ensure greater durability. They feature a lock placed on the bottom so ministers can’t forget to secure them.

Barrow & Gale has also taken to offering an option for those MPs who have not yet reached the heights of holding a ministerial post. It now produces green “House of Commons” boxes, personalised with an MP’s name and a leather strap in their party colour, for up to £1,350.

Mohammed Suleman, a spokesman for the company, said: that at the last election there were orders for 30 to 35 red souvenir boxes.“It is very nice when ministers come directly to us and acknowledge what we do,” he said. We are always very busy around election and reshuffle time. “We’ve been making these boxes for over 100 years and it is important that it doesn’t become a cottage industry.” Mr Suleman declined to say how much ministers paid for their boxes or who bought them. “Ours is a small and very unique service. We aim always to be very discreet and under the radar. “It’s not a matter of creating an air of mystery, we just want to do the job quietly and we don’t aim to cause any fuss along the way.”

Tanks

-

Evan Birchfield had long been fascinated by tanks.

So when it came to his 50th birthday, there was only one present that would do.

As it turned out, buying one was the easy bit. The hard bit was sneaking the behemoth into the tiny West Coast town of Ross, where the Birchfield family runs a gold mine.

"There was a bit of stress involved," says Andrew, one of Evan and wife Jane's three sons. He had been searching the world for a Centurion tank. "That was all he used to talk about."

It's quite a gift. Weighing in at 52 tonnes, the tank was first seen in Europe in 1945, arriving a month after hostilities ended. It was England's answer to Germany's much-feared Tiger tank.

Andrew's online search was so fervent that at one stage the US Department of Defence emailed questioning his interest. "They were telling me to stop."

He didn't, and tracked down a Centurion for sale in Australia.

"We flew over there and bought it," he says. Tanks, by the way, cost about $130,000. Deal done, he turned for the airport. "That's when the headaches started."

Andrew had missed the plane. Normally, that's bother enough. But it becomes even more so when your Dad is the boss, a hard taskmaster, and you've bunked off work to buy him a birthday present in another country.

He rang Evan and lied about where he was, saying he was in Christchurch with a broken-down car, and slipped back to work on the next flight.

Then the tank got sent to the wrong port, turning up in Auckland instead of Nelson. Somebody told the television networks a tank was being imported and soon enough a journalist was on the case.

"We were trying to keep everything quiet," says Andrew, but the journalist had tracked down the business somehow. They were dancing around the office, trying to stop Evan, now 61, from answering the phone.

"A couple of times I said to Mum, 'Let's just tell him'. It'd be far less stressful especially when that TV crew started calling."

They managed to throw the media off the scent and get the tank on another ship, this time bound for Nelson, where an alert inspector noticed mud on the underside.

Andrew bunked off work again. "It was hard getting the time off," he recalls. He went up to Nelson, washed the tank and got it on a transporter down to Stillwater, from where it would be smuggled into Ross.

Jane recalls being worried it would be spotted. "They said, 'Don't worry. We'll stick a cover over it and no one will know what it is'."

So there it sat in a yard in Stillwater, under cover with a bloody great turret sticking out the front. "Well, you couldn't miss what it was," says Jane.

Evan, by now, had heard a whisper and the West Coast well knew he was keen on a tank. As Andrew says, "On the West Coast, you only need to fart and everybody knows."

Jane: "People were ringing him and asking, 'Have you got a tank coming into town?'." Early on, she'd dashed his hopes. "If you think you're getting a tank, I want an apartment on the Gold Coast."

It was such a flat response that, when he rang the transporter driver, he happily accepted the explanation the tank was there for some blackpowder gun club event.

They got the tank down to Cemetery Hill, just north of Ross, before off-loading it. Import regulations meant it wasn't allowed into New Zealand with fuel, so there was a bit of a panic finding more when it spluttered, choked and died out in the open.

Evan reckons he "nearly drove over it" that night, but they had his brother lined up to get him into the pub at the time it was delivered. By the time he did go that way, the tank was stashed in a neighbour's haybarn.

It's never simple, keeping a surprise present under wraps. Evan was up the next day with a bulldozer - he's been driving heavy machinery since age 9 - and heading over to the neighbour's place to do some work.

There were tank treads all over the place, so before Evan got there, the neighbour was in his own tractor driving up and down across the property trying to disguise the tracks. "I've got a new dozer," he tells Evan, which was a terrible excuse really.

Then they panicked, because the work Evan was going to do had him driving back and forth in front of the haybarn where the tank was stashed. So, a friend was recruited as a diversion and put in the cab with Evan. Every time their path went near the doors, the friend struck up a conversation with all the usual shouting and hollering that goes on in a bulldozer.

"We tried to keep it quiet but it was pretty hard to hide," says Jane.

But they did. And then came the birthday.

They were out the back of Birchfields Ross Mining, the expansive base of the gold-mining business, when a red car came belting up the road, hell-for-leather. It swung into the business, sliding to a halt and disgorging a cluster of armed men, all dressed like were in the Special Air Service or some special forces unit. "They came flying in there and started firing," says Evan.

Then came the tank.

It clattered along the road, apparently chasing the SAS guys, who turned their fire on the tank, like they were fighting for their lives. The tank, impregnable, turned into the yard, bore down on the birthday celebrations and rolled straight over the top of the red car.

Andrew says: "We could only run over half of the car because the guy who owned it wanted the engine."

Out popped the opposing force, dressed in a West Coasters' view of what terrorists might wear in 2002, the year after the World Trade Centre attacks. Broadly speaking, it's Middle Eastern.

"I was an Arab," says Andrew. "I was driving it. I got shot."

The SAS team conquered the tank. Evan said: "Then the SAS guys dragged all the Arabs out." The "terrorists" were held at gunpoint and many photographs were taken.

As for the car, the attempt to save the engine didn't work out so well. "It ended up getting smashed up later in the night after a few cordials," says Andrew.

Evan had a good night. "Understandably," he says, "I never went to bed."

Jane did, but woke about 4am. She says she looked out the window, next to where the party was being held, and saw Evan standing there, just staring at the tank. She watched for some time, initially thinking he was alone, then noticed a few other people still up. She watched and he didn't move, just stood there and stared at his tank.

Then, at first light, she was woken again when Evan started up the tank.

"Here we go," she thought. And off he went.

And for a few years, that was the pattern. He doesn't drive over cars anymore: "I got one stuck in the tread and it dug up under the mudguard."

There had been other lessons too. "I went through a house one day. I didn't realise it would break so much stuff off."

Eventually, there were repairs needed. "I went over to Aussie to get some parts for the one I had," says Evan.

The man with the parts said: "Have a look in the shed." And there was a tank. "It's for sale, too," said the man.

Evan wrung out his words with a fair dose of exasperation.

"Hell, don't tell me that," he said.

So that's two tanks. "That's our anti-aircraft gun in the shed there," he says, driving past a chunk of weaponry mounted on the back of a flatbed truck. "That's in case we get a tank coming at us from the air."

Evan was born in Grey Valley, where his dad had a contracting business. Evan started young, helping out with his father's business. The old Bedford truck: he can remember barely being able to touch the pedals.

The work just "dried up overnight" in the 1980s, he says. That was when they moved to Ross and began goldmining. There's a lot of regulation to work through. You ask him about tanks, and he says: "I drove a bulldozer for years and I always thought dealing with some of these public officials, a tank might be more useful."

There were a few people mining at the time and enough work for everyone. It created a collegial environment, he says, in which knowledge and innovation was shared.

The Birchfield business is alluvial mining, using water to separate gold from soil - a sort of massive gold-panning operation. He's aware it's not a universally popular way to make a living. "There's a segment of the community who really hate us with a vengeance."

The company started small but now employs 35 people. The business is a large part of Ross, with many employees able to buy houses in the town. They get well paid, says Evan.

"I can spend millions of dollars on machines but if I don't have good people on them I might as well not bother."

The goldmining business is all-consuming. "You can't have a hobby. If I had a boat or set of golf clubs I'd never use it."

If anything, Evan's hobby is mischief. One day he decided he'd like a dragon. "So we built one," he says. He waves a hand past the workshops and sheds to the back of the yard. "That's its head over there."

Sure enough, it's a dragon and a decent size. Amazing what a man with inclination, and a workshop for heavy machinery, can accomplish.

They call it the Ross Ness Monster and it made its debut when Evan and Jane's son Paul went fishing.

They knew where and when he would be casting a line. The dragon was submerged in the lake, with air canisters on remote control.

Once Paul was settled in, they activated the gas canisters and up floated the dragon, its head quietly breaking the surface just next to the small rowboat.

Paul pretty much flew for the shore. Evan cracks up, his arms are moving at a blur, miming a freaked-out Paul rowing so fast he's flying through the air. "He's in the middle of the air, rowing for the shore."

That was when the tank emerged through the undergrowth. A huge BOOM roared out as pyrotechnics in the barrel ignited, and then there was a BAM as a matching charge went off in the dragon's head.

Oh yes, says Evan: "It's good to have a second childhood."

Iceland's Penis Museum

-

If you ask Icelander Sigurður “Siggi” Hjartarson, the founder of the world’s only phallological—yes, penis—museum, why he’s spent 40-plus years collecting almost 300 different animal phalluses and “penile parts,” his answer is simple: “Well, somebody had to do this.”

He’s not sure why anyone would be weirded out by what he calls the “new science” of phallology. His museum has specimens from the tiny (a hamster, at two millimeters in length) and the large (17 whale penises and counting, one measuring nearly six feet); the ordinary (as ordinary as polar bears and gorillas, anyway) and the mythical (Icelandic elf, troll, and merman phalluses are on display). He has lampshades made from bull scrotums and silver penis sculptures of the Iceland men’s handball team. He even has wooden, penis-shaped phones, mini-bars, and cutlery sets that he carved himself.

“It’s mainly Americans who are squeamish about this,” Hjartarson says over the phone from his home in Iceland. “Maybe at first people were astonished and thought that I was queer or something was wrong with me—but on the whole, it has been pretty successful and the reaction has been good.” Sure, he may be “a wee bit eccentric or whatever” (his words), but his family and the people around him have always been onboard with the collection. In fact, it was his wife, to whom he’s been married for more than fifty years, who suggested he open a museum in the first place. In 1997, twenty-three years after a teacher gave Hjartarson, then headmaster, a bull’s penis cattle whip as a joke, the Icelandic Phallological Museum opened its doors.

But among the hundreds of organs floating in formaldehyde jars and jutting out from wooden mounts on the walls, one specimen was always clearly missing from Hjartarson’s collection: a human penis.

Hjartarson, now 73, and his quest to obtain the ultimate, human addition to his museum’s collection is the subject of Jonah Bekhor and Zach Math’s documentary, The Final Member, which is being released in select theaters on Friday. The film follows Hjartarson and two men—one an aging, famed Icelandic playboy and the other a middle-aged, well-endowed American—in a “race” to see who gets their man bits immortalized in the museum’s vacant “human” jar. All three are wildly colorful characters, making for situations as funny—and punny—as you’d expect. (Guess what the museum’s largest specimen is? A sperm whale! And the official slogan printed on the doors? “It’s all about Dicks.”)

Guess what the museum’s largest specimen is? A sperm whale! And the official slogan printed on the doors? “It’s all about Dicks.” The Final Member unabashedly dissects why penis talk is uncomfortable for so many: "We look at the historical record and see all kinds of variations in how much we can talk openly about penises. It’s odd that we, in the 21st century, tend to fall in a very conservative point of view,” Mitchell B. Morris, a professor of Cultural History at UCLA, says in the film. And it sympathetically conveys each character’s more universal preoccupation: All three men, above all else, just want to be remembered after they die.

95-year-old pioneer Pall Arason—the first man to organize tours to the Icelandic highlands, as well as a renowned womanizer who loved bragging about his “outstanding sexual performances”—passed away in 2011, giving his penis, testicles and scrotum dibs on the jar that is now the museum’s centerpiece. Tom Mitchell, a thrice-divorced Californian obsessed with his own penis—as in, he named it Elmo, tattooed the tip with stars and stripes, and makes costumes for it, which you can gaze upon in all their Viking, wizard, cowboy, and astronaut glory here —was understandably saddened by the news. To beat Arason to the punch, he had planned to have Elmo surgically removed, flown to Iceland, displayed in a special case he designed himself, then returned to his home during the museum’s off-season. But losing his chance to be the museum’s first human member hasn’t stopped him from pursuing a comic book deal in which his schlong stars as a flying, caped superhero.

The documentary ends with the installation of Arason’s penis, greeted with flashing cameras and a beaming Hjartarson. But Hjartarson lets on that there were a few things the film left out.

He was less than satisfied with Arason’s shriveled remains, for one. “His organ had shrunk quite a bit,” Hjartarson says. “Unfortunately, the process of preservation wasn’t successful at all.” Issues with transferring Arason’s remains into the jar of formaldehyde resulted in a gray, wrinkly, mostly unrecognizable mass. It could potentially be replaced with Hjartarson’s own penis, but that may not happen. “The problem is, I’m getting old and I’m shrinking like Mr. Arason,” he says. “So I’m not sure that my son [Hjörtur Gísli Sigurðsson, who took over as curator of the museum two years ago] would like me when the time comes!”

Hjartarson also admits that he doesn’t approve of the way The Final Member ultimately portrayed the acquisition of Arason’s member. “I didn’t know, and they deceived me, or went behind my back, in the way that they never told me that they would put this film up as a ‘race’ between Tom Mitchell and Mr. Arason,” he says. “There was some, well, scheming. I had got Mr. Arason’s [penis] for five months before it was announced to the public that I had got it. That was just for these filmmakers to go on with the play, or the show of some competition between Mr. Arason and Mr. Mitchell. I was not altogether happy about this, but that’s not my job. This is their film and not mine and I just hope they have some success with the film.”

Despite the problems, Hjartarson remains mostly Zen as he awaits whatever is next for the museum—whether it comes in his lifetime or not. Since the documentary was filmed, he has received offers from a German photographer, Peter Christmann, and an English TV personality, John Dower, who both are willing to donate their penises to the museum after they die. Neither is very old (Christmann is in his early 40s and Dower in his 30s), but Hjartarson is in no hurry. “We just wait and our time will come,” he says.”You never know. People die at all ages, you know? We are not stressed by this. Just keep your ears and eyes open and be quick when opportunity comes.”

Vinyl

-

On the 65th birthday of the 45rpm record, vinyl remains in rude health — not just as a music format but also an investment opportunity for the shrewd fan.

The sale of vinyl hit its highest level for 15 years in 2013, with more than a million records sold — a 101 per cent rise on the previous year. Meanwhile, Record Store Day, the annual celebration of independent music stores, takes place next Saturday and each year several bands and record labels put out special, limited edition vinyl for the occasion. For fans this presents a unique opportunity to not only buy some rare music, but also to make a purchase that could appreciate tenfold over a decade. Phil Barton, the owner of the Sister Ray record store in Soho, explains: “In 2004, a mint copy of King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King was worth about £50 and now it’s £500. The Who’s My Generation has gone from £150-£200 to £800-£1,000, the Sex Pistols’ EMI version of Anarchy in the UK from £20 to £300.”

One reason for such a spectacular growth in prices, according to Spencer Hickman, UK co-ordinator for Record Store Day, is the advent of the CD, which led to people discarding their record collections en masse. “Since CDs happened, people got rid of vinyl — you would see it in skips — so a lot of the original pressing didn’t make it through.” The ones that did can now fetch a tidy sum, because “it just so happened that through the years fewer and fewer have come up for sale”.

The rarest records can command staggering prices. Last year a rare blues record, Alcohol And Jake Blues / Ridin’ Horse by Tommy Johnson, recorded in 1929, sold for $37,100 on eBay. Earlier this year, a sealed copy of Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here changed hands for £9,000. If you are hoping to unearth a rare gem from the catalogue of Record Store Day releases — or in the bargain bin at your local charity shop — Mr Barton says the first thing to do is to make sure it’s in excellent condition.

“Always get the best quality, and if you are buying second-hand then get as near mint as possible,” he says. “That applies to the record, not just the cover — both elements have to be as mint as possible, because those records will increase in value more than the rest.

“If you’re buying new records, buy two copies — one to keep in mint condition and one to play. Mint means never played, everything else is not in mint condition.

“Collect the bands that people will always want, such as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, and so on. It’s much harder to predict which records of today’s releases are going to be worth money in coming years.”

Novices should be careful not to assume that everything coming out on Record Store Day is going to be valuable. “There are so many products there that it will be a tricky business to pick out the best ones,” warns Mr Hickman. The best thing is to buy the music you love and want to listen to. Records are an investment, and you will always be able to sell them. In charity shops you can still pick up fantastic records for a lot less than what they’re worth — it’s the thrill of the hunt, because you don’t know what you’ll find.”

Wine Forgeries

-

In 2006, Atlanta wine collector Julian LeCraw Jr. paid $91,400 for a single bottle of 1787 Château d’Yquem, at the time the most ever for a white wine. That purchase, while stunning, was dwarfed in both size and renown by that of one Christopher Forbes, who bid £105,000 (some $157,000) in 1985 for a 1787 Château Lafite etched with the initials “Th.J.,” and advertised as formerly belonging to Thomas Jefferson. The landmark sale inspired other ambitious collectors, including billionaire business tycoon Bill Koch, to seek out their own Jeffersonian wine. In late 1988, Koch spent about half a million dollars to add four of the famed bottles to his personal cellar.

The world of elite wine collecting, as such purchases demonstrate, is an expensive and high-stakes hunting game. Connoisseurs such as Koch, for whom the money is no object, will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on rarities that promise to enhance their collections. But as prices for these bottles have soared, so has another risk—one that LeCraw and Koch both discovered the hard way. The most esteemed and alluring of bottles just might turn out to be fake.

While experts agree that it’s hard to size up the impact of forgery on the wine industry, a recent spate of busts has shone a spotlight on how pervasive the problem might be. This past October, European police arrested seven people in connection with an international counterfeiting ring that sold 400 bottles of fake Romanée-Conti wine, among the world’s most expensive, for more than 2 million euros ($2.7 million). A few months earlier, police in China arrested more than 10 suspects linked to millions of dollars in fake wine sales after uncovering counterfeiting equipment in a raid. LeCraw is suing the seller of his bogus bottle, Antique Wine Co., for $25 million. And in December, a federal jury convicted famed rare wines dealer Rudy Kurniawan of peddling tens of millions of dollars of homebrewed mixes with sham labels.

“Making forgeries of wine bottles, unfortunately, is really not all that difficult and time-consuming, especially since one could assume that making a ‘spot-on’ counterfeit watch would be much more difficult and time-consuming,” says Mark Solomon, the wine director at Leland Little Auction & Estate Sales and CEO of TrueBottle.com, an online database for wine collectors.

Some forgers will print their own labels to alter cheap bottles; others will buy empties of the best years and makes, then refill them with other wines. That means the glass bottles themselves can also fetch substantial sums. The empty bottle of a prized 1982 Château Lafite Rothschild might alone fetch $1,500. “But if you go to 1983 or 1981,” Solomon says, “the price of the bottle is a fraction of what an ’82 goes for.” A clever forger might therefore alter the last digit of the date, refill the bottle, and sell it for several multiples of what the empty cost.

Wine forgeries are as easy to pull off as they are hard to weed out. The bottles are rarely sold directly to auction houses, instead winding their way into collectors’ cellars through a series of sales, where they can hide among dozens of authentic bottles. And while the easiest way to check whether or not your 1982 Château Lafite Rothschild is the real deal might be to taste what’s inside, you can hardly pop the cork off a rare vintage before it goes up for bidding.

Charles Curtis, a Master of Wine and former head of wine for Christie’s in both Asia and the Americas, explains that authenticating wine begins with contacting the owner to request any documentation (receipts and so on). Next comes a physical inspection of the bottle. Experts check the capsule, cork, label, and glass to see if the materials are consistent with the stated time and place of production, if the branding is consistent, and if any of the pieces show signs of tampering. An examiner can also use a high-powered flashlight to examine the cork through the bottle and see if the wine itself is the correct color and contains the proper amount of sediment for its age.

“It is seldom possible to establish authenticity with 100 percent accuracy,” Curtis tells me, “but these methods normally give enough evidence to form a credible opinion of authenticity.”

So how to get at the problem of checking the wine itself? One method has been to enlist carbon dating to approximate the age of the liquid in a bottle, but this can prove imprecise. Instead of looking for carbon, a variation on this approach searches for the isotope cesium-137, an artificial form of radioactivity that was created through nuclear testing and is therefore not present in wines bottled before the advent of such technology. The isotope is absorbed from the soil by the roots of grapevines, and gets locked into the bottle during the winemaking process. Bill Koch’s camp famously sought out Philippe Hubert, a French physicist who had experimented with cesium-137 testing, to have one of his alleged Jeffersonian bottles tested in a lab beneath the Alps on the French-Italian border.

Another answer, which doesn’t require traveling to a remote section of the Alps, may have been found in a device that’s emerged in just the last year. It’s called the Coravin System, and it uses science to do magic—namely, to extract wine from a bottle without removing or even damaging the cork. Coravin is the fanciest corkscrew you’ve ever seen, with a sleek upright design that lets it sit in its holder like a tiny rocket waiting to launch. The creation of medical device inventor Greg Lambrecht, it works by passing a fine, hollow needle through the cork. The bottle is pressurized with argon, an inert gas, that pushes the wine into tiny holes on the side of the needle and out through the device, into your glass.

“The cork is elastic - it’s actually one of the most elastic solids we’ve ever discovered in nature,” Lambrecht says. “I’d made medical needles that did very little damage to the things they went through, so the insight was, ‘Hey, I could use this to get through the cork.’”

Coravin retails for $299 and, for the moment, has two main markets: home consumers and people who sell wine for business (restaurants, distributors, etc.). Coravin allows them to pour or sell a single glass without setting off a ticking oxidation clock that can turn the best of wine into something resembling vinegar. Lambrecht’s initial idea for the device came about because he wanted to keep drinking good wine a glass at a time while his wife was pregnant, and needed a way to preserve the remainder of the bottle.

In a market besieged by fraud and chicanery, could Coravin be the solution? Maybe. Using Coravin to sample a wine prior to a sale would have to be disclosed at auction and could potentially devalue the bottle. But far more problematic is this simple fact: Lots of people don’t know what old wine is supposed to taste like. “People may taste a bottle of genuine old wine that’s matured and may not like the flavors,” Curtis says. “There are some tasters who are superb judges of such matters, and there are others who are not.” Wine tasting, after all, is subjective. For all but the most refined of palates, it has to do as much with what we think of a bottle as what we know. If we think a wine is expensive—and forgers think they know we think that - chances are it will taste that way, too.

Plane Spotters

-

“We couldn’t give a fuck about Obama,” Luke Amundsen says as he stares through a car windshield toward a taxiing Qantas jet. “We just want to take photos of his airplane.”

It’s a horribly windy Friday morning in mid-July at Brisbane Airport, situated 10 miles northeast from the third biggest city in Australia. Amundsen and Simon Coates are sitting in the cabin of a silver Holden Commodore while commercial aircraft alternately take off and touch down. “If there was a private jet due in, we’d come out here just for that,” says Coates. “We don’t care who’s on it — we just want the jet.”

He switches on a dashboard radio unit, which picks up staccato blasts of aviation jargon from the nearby control tower. “…Qantas 950 two-five-zero degrees, three-zero knots — cleared to land,” says a calm male voice. Amundsen exhales, impressed. “Three-zero knots!” he says. “That’s a decent wind.”

Amundsen is a tall 28-year-old, with facial stubble and short, spiked brown hair. He’s the more enthusiastic of the pair. Coates, also 28, plays it much cooler: His eyes are hidden behind sunglasses, and his responses are more measured. He maintains the Brisbane Airport Movements blog, while Amundsen helps run a Facebook page, Brisbane Aircraft Spotting, which has around 6,000 fans. Together, the two have also invested tens of thousands of dollars and a year of their lives in the development of a new website, Global Aircraft Images, which seeks to challenge established spotter-friendly communities such as Airliners.net and Planespotters.net.

While we sit facing the tarmac — the second busiest single airport runway in the world, after London’s Gatwick — a news van glides past. “They must be out here for the Malaysian thing,” says Coates, before turning to me. “Did you hear about the Malaysian that went down?” It’s July 18, 2014, the day that news breaks of MH17’s wreckage being scattered across the Ukrainian countryside. Amundsen reveals that he has flown on that destroyed Malaysia Airlines plane, while Coates has flown on MH370, the one that went missing in March. They know this because they both keep records of every flight they’ve ever taken.

“We’re pretty serious about it,” Amundsen continues. “At home, Simon and I have got ADS-B receivers; with those, on our computer screens at home, we can virtually see exactly what the air traffic controllers can see. If something unusual pops up on our radar screen, that’ll usually give us half an hour to get out here and catch it.” (Neither of them can recall what ADS-B stands for, so Coates googles it: Automatic Dependent Surveillance — Broadcast.) A plane-tracking website named FlightRadar24 feeds off these receivers. Coates opens the app on his phone, which shows a bunch of tiny yellow icons overlaid on a map. “You can see all the planes buzzing around,” he says.

“This app runs off people’s home feeds,” Admundsen explains.

We meet at what’s known as “The Loop” — one end of Acacia Street, which borders Brisbane Airport and offers the best runway-side sight lines for spotters, including a raised concrete viewing platform. At age 15, Amundsen began learning to fly at flight school; a year later, he was flying a skydiving plane for fun and profit, and by 19 he had obtained his commercial pilot license. He has clocked over 3,000 hours in the cockpits of airplanes and helicopters. Coates is employed by the Qantas Group too, as a ground handling agent here at Brisbane Airport — a job that, he says with a smile, involves “passenger marshaling, boarding flights, standing out on the apron, getting high on aviation fuel every day.” He jokes that he has logged over 800 “backseat hours” on commercial flights.

Through the windshield, we watch a red-tailed Boeing 747 take off. “See, there we go, he’s off to Singapore,” says Amundsen, pointing. “He’s up nice and early.”

“Very early variation,” says Coates, admiring the steep ascent.

“That’s, like, a QF8 rotation. He’s got awesome headwind. The wind’s coming from the south, and going over the wing.” They know the Qantas jet is heading to Singapore because it ascended so sharply. “There’s two [Qantas] 747s,” says Amundsen. “One goes to L.A., one goes to Singapore. The L.A. one goes out a hell of a lot heavier; it would have over 100 tons of fuel on board. That would only have about 60,” he says, pointing again at the now-distant aircraft, growing smaller by the second.

Amundsen knows these routes and schedules particularly well, as he lives nearby. “If I could live closer, I would,” he says. “I can be lying in bed at midnight and hear the Emirates 777 come over, and know exactly what it is, straightaway. I don’t even have to look up.”

Amundsen’s comment about the presidential plane arises as the pair discuss the upcoming G20 summit in November. These two will be among the crowd attempting to gather somewhere near this airport, cameras in hand, searching the skies for Air Force One in the hope of capturing a once-in-a-lifetime event: the president of the United States of America landing at their home airport. An intense Australian Federal Police presence surrounding the miles of wire fences day and night for the duration of the summit mean that shooting Air Force One is an unlikely event indeed. But still, the possibility is there.

And possibility is what drives planespotters — otherwise known as “jetrosexuals,” “aerosexuals,” and “cloud bunnies” — a niche group of obsessives whose intense interest in flight paths, travel schedules, and colorful jet livery occasionally overlaps with the concerns of the general population.

When Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370 vanished on March 8, 2014, planespotting had its best chance at making a mainstream impact. While millions combed satellite images online to look for signs of wreckage, a 32-year old designer and filmmaker based in Jersey City, New Jersey, named Michael Raisch had a different approach: to collaborate with global planespotters and create a visual tribute to the aircraft. Raisch searched MH370’s tail number — 9M-MRO — and emailed around 80 spotters who had photographed the plane. Raisch says, “I had the simple thought, ‘You captured this little thing that’s gone, it’s not coming back, no one can take this picture again — how do you feel?’”

Ultimately, 22 spotters from around the world replied and offered Raisch shots they had taken from 2004 to February 2014. His tribute functioned as a kind of eulogy for the physical aircraft, and it struck a chord, attracting 120,000 visitors in the month after its publication on March 30. “The planespotters gave us a human connection to this missing plane, and I think that’s why it went viral,” Raisch says.

To seasoned sky spies like Amundsen and Coates, such headlines are viewed as sideline attractions rather than the main event. Rather than chasing the loudest sirens and smoldering wreckage, theirs is a process of passion — they show up day after day, week after week, and cast their eyes toward the runway. But since September 2001, any pastime involving the close scrutiny of commercial aircraft cannot be seen as wholly innocent.

In front of our parked car are a father and son, lying in the back of their four-wheel drive to escape the wind, doing exactly the same thing as we are. Later, Amundsen says, “I just broke up with my missus, mate. That’s a good thing, you know? I reckon spotting was more important than her!”

Coates cackles. “Amen to that!”

While modern planespotting may appear to some as a rather strange and tedious way to spend free time, the hobby has its roots in the serious business of wartime watchfulness. During World War II, British and American governments distributed cards to citizens that included illustrations showing the differences between Allied and Axis aircraft, so that those with their eyes to the sky could determine whether to wave patriotically or seek cover from incoming ordnance.

Nowadays, a search for planespotting on YouTube returns over a million results, and the most popular video has been viewed over 7.5 million times. It was uploaded in August 2013 by an account named TheGreatFlyer, run by Demetris Gregoriou, who lives in Nicosia, the capital of the European island nation of Cyprus. He is 17 years old.

Titled “Low Landings and Jetblasts – A Plane Spotting Movie,” the four-minute clip was filmed on the small Greek island of Skiathos, where enormous jets land on a beach-approach runway that spans the entire width of part of the tiny tourist paradise and allows spotters to get unusually up close and personal. Gregoriou makes a pilgrimage there every year. “People cannot believe I spend eight days [on] such a beautiful island, all of them by the end of the runway,” he says. The young filmmaker describes Skiathos as “the second St. Maarten,” in reference to another famously low-altitude runway at Princess Juliana International Airport, on the Caribbean island, which acts as a magnet for the global planespotting community and curious tourists alike.

Near the beginning of the video, a sign warns DANGER: PLEASE KEEP AWAY FROM AIRCRAFT BLAST, yet Gregoriou captures on film plenty of sandal-wearing enthusiasts attempting to hold onto a steel fence while they’re buffeted by high-speed winds, sand, and debris. At one point, a man attempts to let go, only to collapse on his knees in the middle of the road as the wind roars through his hair. At another, a slow-motion replay of an Air Italy 737 seems to show its wheels missing the fence by inches. “Many consider planespotting a rather boring sport,” Gregoriou says. “They always get impressed after watching my videos.”

One of the most popular videos uploaded by a user named Dantorp Aviation is a 31-minute “wingview” video of a British Airways 747-400 taking off from New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. The footage is taken from a single camera, filming the aircraft pushing off from the aerobridge and taxiing to the runway, while passengers and crew chatter in the background. The video essentially shows modern air travel in all its minutiae, including the standard in-flight warnings that smoking is not permitted, and that passengers are required to switch off their phones.

“When I talk to the average person about my YouTube channel, they’re like, ‘What, people actually watch that?’” says Dantorp, the alias of 17-year-old Daniel G., who is based in Gothenburg, Sweden. (He requested that his surname not be used.) Since being uploaded in September 2013, that video has received over 630,000 views, and, all told, Dantorp’s 290-odd aviation videos have been viewed nearly 10 million times. But…why? “I wish I knew,” he says with a laugh. “Apart from the airport, YouTube is the closest to aviation you can get.”