Computers and the Internet

1. Free Ride With Google

2. Ray Kurzweil

3. Online Computer Courses

4. Ethics

5. Klout

6. Just Because You're Not On Facebook

7. Why Is Everyone So Angry?

8. Apple AirPlay and the Window of Obsolescence

9. Google Easter Eggs

10. Internet Pirates Will Always Win

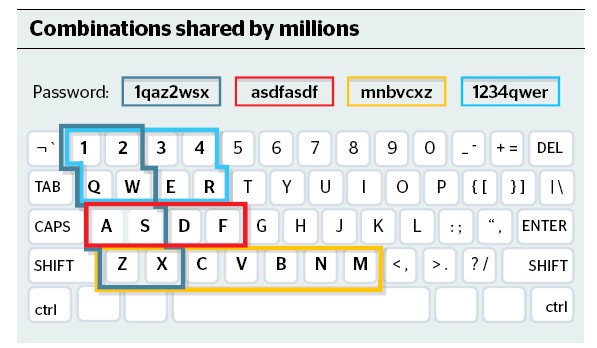

11. Passwords

12. Avatars

13. 5 People Making A Killing Out Of Piracy

14. The Drawback of Free

15. When Algorithms Go Wrong

16. Captcha, ReCaptcha and Luis von Ahn

17. AI

18. Russia and Spam

19. The Story of Skype

20. Open Data

21. What We Hate About The Internet

22. Quora

23. Video Game Cheats

24. Net Neutrality

25. Why Do Trolls Troll?

26. Robo Brain

27. More On Trolls

28. You're Continually Being Experimented On

29. Facebook 'Like' Addiction

30. The First MUD

31. The Third Industrial Revn

32. Troll Hunters

33. Easy Hacking

34. Web Pages Aren't Forever

35. QAD Home Security With A Smartphone

36. The algorithms that run our lives

37. Preserving Data

38. Hooking Customers

39. Policing Facebook et al

40. Passwords 2

41. Virtual Crimes?

42. Rise of the Robots

43. Moore's Law Keeps Going

44. The Racist Internet

45. Hacking Your Home

46. Terms and Conditions

47. Fair Algorithms

2. Ray Kurzweil

3. Online Computer Courses

4. Ethics

5. Klout

6. Just Because You're Not On Facebook

7. Why Is Everyone So Angry?

8. Apple AirPlay and the Window of Obsolescence

9. Google Easter Eggs

10. Internet Pirates Will Always Win

11. Passwords

12. Avatars

13. 5 People Making A Killing Out Of Piracy

14. The Drawback of Free

15. When Algorithms Go Wrong

16. Captcha, ReCaptcha and Luis von Ahn

17. AI

18. Russia and Spam

19. The Story of Skype

20. Open Data

21. What We Hate About The Internet

22. Quora

23. Video Game Cheats

24. Net Neutrality

25. Why Do Trolls Troll?

26. Robo Brain

27. More On Trolls

28. You're Continually Being Experimented On

29. Facebook 'Like' Addiction

30. The First MUD

31. The Third Industrial Revn

32. Troll Hunters

33. Easy Hacking

34. Web Pages Aren't Forever

35. QAD Home Security With A Smartphone

36. The algorithms that run our lives

37. Preserving Data

38. Hooking Customers

39. Policing Facebook et al

40. Passwords 2

41. Virtual Crimes?

42. Rise of the Robots

43. Moore's Law Keeps Going

44. The Racist Internet

45. Hacking Your Home

46. Terms and Conditions

47. Fair Algorithms

Free Ride

-

Google is everywhere you look, even when you're not online.

But it is not only ubiquitous, it is also, apparently, free. It is tempting, therefore, to see it as like air, necessary and morally and commercially neutral. Surely, therefore, there is nothing wrong with our leaders mingling with this company?

There is. Google is no more neutral than a party manifesto. It has an agenda based on one highly specialised interpretation of how the internet must work and evolve. Essentially, the company wants to rewrite copyright and intellectual property laws in the cause of making all the information in the world freely available. Google uses its near monopoly in internet searches to sell advertising, and the more material there is to search the more advertising can be sold.

This is a utopian vision and, like all such visions, it involves destruction. If your music, your newspapers, your films, your television, your books are all free, then, in time, they will no longer be produced because there will be no economic justification. Already, Robert Levine points out, the music business is trapped in a downward spiral that will end in oblivion; newspapers, especially in America, are going the same way; and films and television are being pirated on a huge scale.

"It's amazing," Levine writes, "how easy the internet makes it to destroy a business without creating another one in its place." Governments, when they are not lunching Google, are struggling to come up with an answer.

But the technology moves too quickly for politicians - Vince Cable, only recently, had to abandon plans to force the blocking of filesharing websites as cumbersome and unworkable. For politicians everything, when they gaze into the mire of internet wire, becomes too difficult.

The irony in all this is that the internet is largely parasitic on the media it is so ruthlessly destroying. Blogs would cease to exist without the mainstream media; there would cheaply replicated and, therefore, pirated. As fast as copyright owners think up ways of preventing this, the pirates think of ways of getting round their codes, paywalls or lawyers. I suspect the word "piracy" is part of the problem; it makes young geek hackers think they are Johnny Depp rather than common thieves.

One of the characters in this book is the elusive Christian Schmid, the founder of RapidShare. This, ingeniously, is a "locker service" - it acts as an innocent back-up system by enabling users to upload their material, but, in fact, it is used to access copyright material. As a result, it generates 1% of global internet traffic - as much as Facebook. The law fights with RapidShare, but so far with no conclusive victory. Schmid, meanwhile, gets very rich indeed thanks to the creative efforts of others.

Levine relentlessly ploughs through this and many other twists and turns of the war between the pirates, utopians and the copyright holders. It becomes clear after a while that there is no immediate or even likely solution. Plainly a radical internet land grab that destroyed net neutrality - the way all information is treated equally by the net whether it is from you and me or a giant corporation - and parcelled it out to commercial interests such as television or radio is undesirable. The utopians are half right when they celebrate the freedom and universality of the internet.

But, equally plainly, the claims of utopians such as the science-fiction novelist Cory Doctorow, who gave a speech entitled How Copyright Threatens Democracy, are missing a big point - copyright built and guarantees democracy. Furthermore, the utopians should be aware that, though they see themselves as freedom fighters, they are serving the interests of some of the biggest, most powerful companies in the world.

The solutions offered towards the end of this book are complicated and varied rather than plausible. Typically, they would involve a small, regular charge - say, for access to all of a company's films and television shows - that would create a pile of cash to be distributed to creators on the basis of the popularity of their works. This wouldn't stop piracy but, if the service was well designed, it would make it less attractive.

Where this will end is anybody's guess. In the immortal words of the great screenwriter William Goldman, "nobody knows anything". Neither the blasted heath of the utopians nor the walled gardens of those who would grab the territory of the internet seem attractive prospects. But two thing are clear: chancellors of the exchequer should not co-write articles with blatant commercial players ( should one really have to say this?) and economic advice from Google comes with wires attached. be no music or movies to pirate if there were no record companies or studios. On the internet wasteland of the utopians, only a few feeble amateur shoots would grow.

Or maybe not. Like Google, Levine's book has an agenda but it is the opposite of Schmidt's. Levine, an American technology and music journalist, is on the side of the decently rewarded creators against the utopians. Free Ride is flatly written and hard going, but it is important, not least because it concludes by offering some possible solutions to the problem.

And the problem, at heart, is replicability.

Ray Kurzweil

-

Androids and angels

Futurist and inventor Ray Kurzweil believes humans will soon be able to live forever with the help of computers. Barmy or brilliant?

IT USED to be that you would go into a dark tent where an old woman would gaze into a ball and tell you about the dark handsome stranger in your future.

In the 21st century, it seems, the tent is a rather eccentrically decorated office in the suburbs of Boston; the old woman, a professorial chap in a suit; and the handsome stranger, a network of hyper-intelligent computers that will take over the world.

It is hard not to think Arnold Schwarzenegger while talking to futurist Ray Kurzweil. This is not because he looks like Arnie (he is pretty much the physical opposite), but because he keeps saying things that sound like the plot of the movie Terminator. Nanobots, self-aware computers and human cyborgs litter his conversations.

The media love Kurzweil because his predictions are so bold and expressed with utter certainty. He says that in the first half of this century there will be a ''Singularity'', a period of incredibly rapid technological change, triggered by the moment that computers become smart enough to improve themselves without human intervention.

He sets 2029 as the year computers will overtake humans - which is when things start getting really weird. Disease will be cured, death defeated, the universe will become the playground of immortal super-beings.

"Every aspect of human life will be irreversibly transformed," says Kurzweil, who is due in Melbourne this month. Computers will enter our bodies and brains. The pace of change will be incomprehensible unless we enhance ourselves with artificial intelligence boosts.

"What Ray does consistently," says Neil Gershenfeld from MIT university, "is take a whole bunch of steps everyone agrees on, and take principles for extrapolating that everyone agrees on - so they lead to things that nobody agrees on - things that seem crazy".

But Kurzweil has serious, respectable chops in the prediction business. While these days he makes a fortune on the lecture circuit, much of his early success came as an inventor, forseeing needs that technology would soon be able to fulfil, then coming up with the gadgets to do it.

He started early. The way he tells it, a hospital in Spanish Harlem hired him to do statistics for a government program that provided preschool help for underprivileged families. He used electromechanical calculators with levers and gears to work out simple sums. But he was frustrated by their clunkiness.

"I discovered they actually had a computer, one of the 12 in New York City, in the building. I taught myself to program and wrote a program to do these [statistics]. They were surprised."

No wonder. He was 12 years old.

Kurzweil grew up in Queens, New York, born a few years after his parents had fled Hitler's Europe. They were a talented family. His grandmother was the first woman in Europe to get a PhD in chemistry, his father a successful concert pianist and conductor, his mother an artist.

"The family religion was the power of human ideas," Kurzweil says. Their idea of a sacred text was a da Vinci manuscript. He had an uncle who was a researcher at Bell Laboratories and introduced his nephew to early computers.

Kurzweil loved gadgets from an early age - aged eight he built his own mechanical puppet theatre and later he would build his own computers from surplus electronics. He was inspired by computers, "the idea that you could recreate the world, the thinking process."

At 17 he appeared on the TV game show I've Got a Secret and played a piece of piano music. One of the contestants guessed correctly that Kurzweil had programmed a computer that composed the piece itself, after analysing the patterns in 'real' music.

His path was set. Inventions he has had a hand in include the earliest flatbed scanner and a text-to-voice reader for the blind (used and endorsed by Stevie Wonder).

Gradually Kurzweil turned from inventor to futurist as his ambition and imagination flew further from practical products.

In the prediction business Kurzweil, though by no means infallible, seems to have had more hits than most. The one he is proudest of was predicting the date to within a year - and a decade before the fact - when the first chess computer would beat a human.

Then he latched on to the idea of Singularity. It was not his originally - science fiction writer Vernor Vinge was one of the first to propose it in detail, and the ''father of the computer'' John von Neumann also pondered it.

Kurzweil developed it into a "Law of Accelerating Returns", predicting exponential growth in power in anything technological. Think of how amazingly far we've come, he says, and there's no reason things won't just get more and more amazing, more and more quickly, because each new technology is built on the shoulders of the one before, until that dizzying "Singularity" where we lose track altogether.

In bestselling books and $30,000-a-pop lectures, Kurzweil describes Singularity as "the destiny of the human-machine civilisation."

Critics point to strong signs that the increase in computer power is starting to slow down. The cost of R&D has gone up with every computer generation, so a faltering economy could cause the law to fail. Others say there are various physical limits on computer circuits that will halt progress, possibly in only 10 years' time. Still others wonder what is going to power this vast new computer network.

Kurzweil isn't worried. He says new discoveries will inevitably cause things to pick up. In 40 years, he points out, we have gone from computers that filled a room and cost millions of dollars to massively faster ones that fit in a pocket and cost $100. In the next 40 years we will go from a unit that fits in your pocket to one the size of a blood cell - all running on solar power.

The future is closer than we think. We are already living in a society that depends on smart machines, he says.

"There's no question we don't have our hand on the plug - we could not turn off all the computers,"' he says. "Our civilisation's infrastructure would grind to a halt, all communication would stop, transportation would stop, financial markets would totally freeze up."

"We are increasingly dependent on machine intelligence as machines get more intelligent. But this is not an invasion from Mars. We have always been a human-machine civilisation, we create tools to extend our reach."

But there is a difference between machines getting better at their jobs, and their gaining artificial intelligence and self-awareness.

Kurzweil concedes that consciousness is still a mystery, in terms of how it comes about or how we can be sure it exists in a machine (or indeed a person). But he sidesteps this, saying that once a machine acts like a self-aware being, it might as well be, and people will perceive it as one - again by that magic date of 2029.

"[It's the] 'acts like a duck' test," he says. "If it really seems conscious and it's convincing, I will believe it is conscious. That's really the only test that matters."

When Watson the Computer won the US game show Jeopardy! earlier this year, Kurzweil saw a glimpse of the future he had predicted. "That's viscerally impressive," he says

Not everyone buys into Kurzweil's view of the future. In fact, he has many critics. One scientist called into a TV program he was on to complain that the producers had given time to this "highly sophisticated crackpot", a purveyor of "pseudo-religious predictions that have no basis in objective reality."

When Kurzweil dips into a subject such as biology or artificial intelligence, hard-core researchers tend to argue he has glossed over complexities that will make progress much slower. For example, computers may be getting ever faster at recalling data, but they still can't tell the difference between a dog and a cat.

One of Kurzweil's critics is scientist and blogger PZ Meyers ("pseudo-scientific dingbat" was a particularly stinging conclusion to a recent post).

"The heart of the Kurzweil method is to simply pick a date far enough in the future that we cannot predict what technological advances will occur, and also far enough forward that he isn't likely to be confronted with his failure by people who remember what he said, and all is good," Meyers wrote a year ago, during a spicy exchange over when we would "reverse-engineer" the brain to understand its inner workings.

Meyers also picks at Kurzweil's fondness for the word ''exponential'', saying it can't be used as a magic wand to wave at any currently intractable problem.

But Kurzweil also has plenty of supporters who respect his intellect and his predictions - although some debate his optimistic timeline and utopian assumptions.

Well-respected Australian philosopher David Chalmers, from New York University, believes the idea of the Singularity, while it may not actually come to pass, is credible enough that we should take it seriously and consider its implications.

Kurzweil accuses his critics of lack of imagination - or of resisting the idea of technological immortality, because of a superstitious belief that we have to stay on good terms with death.

Kurzweil's palpable fear of death ("It's such a profoundly sad, lonely feeling that I really can't bear it") infuses his work to such a degree that you wonder if his predictions are wish-fulfillment.

The death of his father at 58 from heart disease and an early diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes have made Kurzweil extremely health-conscious. He has his blood taken and checked every month, and downs 200 pills of vitamins, minerals and other concoctions every day (he calls it "reprogramming my biochemistry"). He describes death as a "looming disaster", a "looming tragedy."

"People believe that this disaster is a good thing, that the goal of life is to become comfortable with death," he says. "People have come to rely on these philosophies as a way of coping with this fundamental anxiety that permeates human life."

Kurzweil intends never to die.

"That's the goal," he says. Healthy living will keep him alive for at least another 15 years ("I'm really not ageing very much," he says), at which point he believes he will be able to directly program his genes to recover youth. Then 'nanobots' will live inside the body and do a better job than flesh and blood in keeping us going. And finally man will merge with machine and 'upload' to a cyber-life.

"That's my plan," he says. "It's not guaranteed to work, but I am optimistic it will. Some people define humanity based on our limitations. I define humanity as that species which seeks to overcome its limitations, and has done so, time and time again."

Online Computer Courses

-

Parlez-vous Python? What about Rails or JavaScript? Foreign languages tend to wax and wane in popularity, but the language du jour is computer code.

The market for night classes and online instruction in programming and Web construction, as well as for iPhone apps that teach, is booming. Those jumping on board say they are preparing for a future in which the Internet is the foundation for entertainment, education and nearly everything else. Knowing how the digital pieces fit together, they say, will be crucial to ensuring that they are not left in the dark ages.

Some in this crowd foster secret hopes of becoming the next Mark Zuckerberg. But most have no plans to quit their day jobs - it is just that those jobs now require being able to customize a blog's design or care for and feed an online database.

"Inasmuch as you need to know how to read English, you need to have some understanding of the code that builds the Web," said Sarah Henry, 39, an investment manager who lives in Wayne, Pa. "It is fundamental to the way the world is organized and the way people think about things these days." Ms. Henry took several classes, including some in HTML, the basic language of the Web, and WordPress, a blogging service, through Girl Develop It, an organization based in New York that she had heard about online that offers lessons aimed at women in a number of cities. She paid around $200 and saw it as an investment in her future.

"I'm not going to sit here and say that I can crank out a site today, but I can look at basic code and understand it," Ms. Henry said. "I understand how these languages function within the Internet." Some see money to be made in the programming trend.

After two free computer science classes offered online by Stanford attracted more than 100,000 students, one of the instructors started a company called Udacity to offer similar free lessons. Treehouse, a site that promises to teach Web design, picked up financing from Reid Hoffman, the founder of LinkedIn, and other notable early investors.

General Assembly, which offers workroom space for entrepreneurs in New York, is adding seven classrooms to try to keep up with demand for programming classes, on top of the two classrooms and two seminar rooms it had already. The company recently raised money from the personal investment fund of the Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and DST Global, which backed Facebook.

The sites and services catering to the learn-to-program market number in the dozens and have names like Code Racer, Women Who Code, Rails for Zombies and CoderDojo. But at the center of the recent frenzy in this field is Codecademy, a start-up based in New York that walks site visitors through interactive lessons in various computing and Web languages, like JavaScript, and shows them how to write simple commands.

Since the service was introduced last summer, more than a million people have signed up, and it has raised nearly $3 million in venture financing.

Codecademy got a big break in January when Michael R. Bloomberg, the mayor of New York, made a public New Year's resolution to use the site to learn how to code. The site is free. Its creators hope to make money in part by connecting newly hatched programmers with recruiters and start-ups.

"People have a genuine desire to understand the world we now live in," said Zach Sims, one of the founders of Codecademy. "They don't just want to use the Web; they want to understand how it works."

The blooming interest in programming is part of a national trend of more people moving toward technical fields. According to the Computing Research Association, the number of students who enrolled in computer science degree programs rose 10 percent in 2010, the latest year for which figures are available.

Peter Harsha, director of government affairs at the association, said the figure had been steadily climbing for the last three years, after a six-year decline in the aftermath of the dot-com bust. Mr. Harsha said that interest in computer science was cyclical but that the current excitement seemed to be more than a blip and was not limited to people who wanted to be engineers. "To be successful in the modern world, regardless of your occupation, requires a fluency in computers," he said. "It is more than knowing how to use Word or Excel but how to use a computer to solve problems." That is what pushed Rebecca Goldman, 26, a librarian at La Salle University in Philadelphia, to sign up for some courses. She said she had found herself needing basic Web development skills so she could build and maintain a Web site for the special collections department she oversees.

"All librarians now rely on software to do our jobs, whether or not we are programmers," Ms. Goldman said. "Most libraries don't have an I.T. staff to set up a server and build you a Web site, so if you want that stuff done, you have to do it yourself."

The challenge for Codecademy and others catering to the hunger for technical knowledge is making sure people actually learn something, rather than dabble in a few basic lessons or walk away in frustration.

"We know that we're not going to turn the 99 percent of people interested in learning to code into the 1 percent who are really good at it," said Mr. Sims of Codecademy. "There's a big difference between being code-literate and being a good programmer."

Some who have set their sights on learning to program have found it to be a steep climb. Andrew Hyde, 27, who lives in Boulder, Colo., has worked at start-ups and is now writing a travel book. He said he leaped at the chance to take free coding classes online.

"If you're working around start-ups and watching programmers work, you're always a little bit jealous of their abilities," he said. But despite his enthusiasm, he struggled to translate the simple commands he picked up through Codecademy into real-world development. "It feels like we're going to be taught how to write the great American novel, but we're starting out by learning what a noun is," he said.

Mr. Sims said he was aware of such criticisms and that the company was working to improve the utility of its lessons.

Seasoned programmers say learning how to adjust the layout of a Web page is one thing, but picking up the skills required to develop a sophisticated online service or mobile application is an entirely different challenge. That is the kind of technical education that cannot be acquired by casual use for a few hours at night and on the weekends, they say.

"I don't think most people learn anything valuable," said Julie Meloni, who lives in Charlottesville, Va., and has written guides to programming. At best, she said, people will learn "how to parrot back lines of code," when they really need "knowledge in context to be able to implement commands."

Even so, Ms. Meloni, who has been teaching in the field for over a decade, said she found the groundswell of interest in programming, long considered too specialized and uncool, to be an encouraging sign. "I'm thrilled that people are willing to learn code," she said. "There is value here. This is just the first step."

Ethics

-

BACK in 2004, as Google prepared to go public, Larry Page and Sergey Brin celebrated the maxim that was supposed to define their company: “Don’t be evil.” But these days, a lot of people — at least the mere mortals outside the Googleplex — seem to be wondering about that uncorporate motto.How is it that Google, a company chockablock with brainiac engineers, savvy marketing types and flinty legal minds, keeps getting itself in hot water? Google, which stood up to the Death Star of Microsoft? Which changed the world as we know it?

The latest brouhaha, of course, involves the strange tale of Street View, Google’s project to photograph the entire world, one street at a time, for its maps feature. It turns out Google was collecting more than just images: federal authorities have dinged the company for lifting personal data off Wi-Fi systems, too, including e-mails and passwords.

Evil? Hard to know. But certainly weird — and enough to prompt a small fine of $25,000 from the Federal Communications Commission and, far more damaging, howls from Congress and privacy advocates. A Google spokeswoman called the hack “a mistake” and disagreed with the F.C.C.’s contention that Google “deliberately impeded and delayed” the commission’s investigation.Many people might let this one go, were it not for all those other worrisome things at Google. The company has been accused of flouting copyrights, leveraging other people’s work for its benefit and violating European protections of personal privacy, among other things. “Don’t be evil” no longer has its old ring. And Google, an underdog turned overlord, is no humble giant. It tends to approach any controversy with an air that ranges somewhere between “trust us” and “what’s good for Google is good for the world.”

But ascribing what’s going on here solely to the power or arrogance of a single company misses an important dimension of today’s high-technology business, where there are frequent assaults, real or perceived, on various business standards and practices.

Mark Zuckerberg has apologized multiple times for Facebook’s changing policies on privacy and data ownership. Last year, he agreed to a 20-year audit of Facebook’s practices. Jeffrey P. Bezos has been criticized for how Amazon.com shares data with other companies, and what information it stores in its browser. And Apple, even before it drew fire for the labor practices at Foxconn in China, had trouble over the way it handled personal information in making music recommendations.

When such problems arise, executives often stare blankly at their accusers. When a company called Path was recently found to be collecting the digital address books of its customers, for instance, its founder characterized the process as an “industry best practice.” He reversed the policy after a storm of criticism.

WHAT’S going on, when business as usual in such a dynamic industry makes the regulators — and the public — nervous?

Part of Google’s problem may be no more than an ordinary corporate quandary. “With ‘Don’t be evil,’ Google set itself up for accusations of hypocrisy anytime they got near the line,” says Roger McNamee, a longtime Silicon Valley investor. “Now they are on the defensive, with their business undermined especially by Apple. When people are defensive they can do things that are emotional, not reasonable, and bad behavior starts.”

But “Don’t be evil” also represents the impossibility of a more nuanced social code, a problem faced by many Internet companies. Nearly every tech company of significance, it seems, is building technologies that are producing an entirely new kind of culture. EBay, in theory, can turn anyone on the planet into a merchant. Amazon Web Services gives everyone a cheap supercomputer. Twitter and Facebook let you publish to millions. And tools like Google Translate allow us to transcend old language barriers.

“You want a company culture that says, ‘We are on a mission to change the world; the world is a better place because of us,’” says Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn and a venture capitalist with Greylock Partners. “It’s not just ‘we create jobs.’ A tobacco company can do that.”

“These companies give away a ton of value, a public good, with free products like Google search, that transforms cultures,” Mr. Hoffman says. “The easy thing to say is, ‘If you try to regulate us, you’ll do more harm than good, you’re not good social architects.’ I’m not endorsing that, but I understand it.”

The executives themselves don’t know what their powerful changes mean yet, and they, like the rest of us, are dizzied by the pace of change. Sure, automobiles changed the world, but the roads, gas stations and suburbs grew over decades. Facebook was barely on the radar five years ago and now has a community of more than 800 million, doing things that no one predicted. When the builders of the technology barely understand the effect they are having, the regulators of the status quo can seem clueless.

Moreover, arrogance can come easily to phenomenally well-educated people who have always been at the top of the class. Success, though sometimes fickle, comes fast, and is registered in millions and billions of dollars. The world applauds, so it’s easy to see yourself as a person who can choose well for the world.

In the “people like us” haze of the rarefied realms of tech, it’s easy to forget that, well, not everyone is like us. Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of sharing personal information, of living in full view on the Web. And, of course, ordinary people have more downside risk than a 26-year-old Harvard dropout billionaire.

Another hazard is also one of the great strengths of the Silicon Valley: a tolerance of failure. Failing at an interesting project is seen as an important kind of learning. In the most famous case, Steve Jobs was driven from Apple, then failed in his NeXT Computer venture and for a while floundered at Pixar. But he picked up vital skills in management and technology along the way. There are a thousand lesser such stories.

If tech is building a new culture, with new senses of the private and the shared, the failure of overstepping boundaries is also the only way to learn where those boundaries have shifted. It is a self-serving point, but that doesn’t mean it’s entirely wrong. To the outsiders, it can look a lot as if the companies are playing “catch us if you can” by continually testing, and sometimes exceeding, boundaries.

IS there a better way? Mr. Hoffman says he thinks the tech industry has to acknowledge how much its products are shaping society. “We need something more than, ‘We’re good guys, trust us,’ ” he says. “There should be an industry group that discusses overall issues around data and privacy with political actors. Something that convinces them that you are good guys, but gives them a place to swoop in.”

Klout

-

Last spring Sam Fiorella was recruited for a VP position at a large Toronto marketing agency. With 15 years of experience consulting for major brands like AOL, Ford, and Kraft, Fiorella felt confident in his qualifications. But midway through the interview, he was caught off guard when his interviewer asked him for his Klout score. Fiorella hesitated awkwardly before confessing that he had no idea what a Klout score was.

The interviewer pulled up the web page for Klout.com—a service that purports to measure users’ online influence on a scale from 1 to 100—and angled the monitor so that Fiorella could see the humbling result for himself: His score was 34. “He cut the interview short pretty soon after that,” Fiorella says. Later he learned that he’d been eliminated as a candidate specifically because his Klout score was too low. “They hired a guy whose score was 67.”

Partly intrigued, partly scared, Fiorella spent the next six months working feverishly to boost his Klout score, eventually hitting 72. As his score rose, so did the number of job offers and speaking invitations he received. “Fifteen years of accomplishments weren’t as important as that score,” he says.

Much as Google’s search engine attempts to rank the relevance of every web page, Klout—a three-year-old startup based in San Francisco—is on a mission to rank the influence of every person online. Its algorithms comb through social media data: If you have a public account with Twitter, which makes updates available for anyone to read, you have a Klout score, whether you know it or not (unless you actively opt out on Klout’s website). You can supplement that score by letting Klout link to harder-to-access accounts, like those on Google+, Facebook, or LinkedIn. The scores are calculated using variables that can include number of followers, frequency of updates, the Klout scores of your friends and followers, and the number of likes, retweets, and shares that your updates receive. High-scoring Klout users can qualify for Klout Perks, free goodies from companies hoping to garner some influential praise.

But even if you have no idea what your Klout score is, there’s a chance that it’s already affecting your life. At the Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas last summer, clerks surreptitiously looked up guests’ Klout scores as they checked in. Some high scorers received instant room upgrades, sometimes without even being told why. According to Greg Cannon, the Palms’ former director of ecommerce, the initiative stirred up tremendous online buzz. He says that before its Klout experiment, the Palms had only the 17th-largest social-networking following among Las Vegas-based hotel-casinos. Afterward, it jumped up to third on Facebook and has one of the highest Klout scores among its peers.

Klout is starting to infiltrate more and more of our everyday transactions. In February, the enterprise-software giant Salesforce.com introduced a service that lets companies monitor the Klout scores of customers who tweet compliments and complaints; those with the highest scores will presumably get swifter, friendlier attention from customer service reps. In March, luxury shopping site Gilt Groupe began offering discounts proportional to a customer’s Klout score.

Matt Thomson, Klout’s VP of platform, says that a number of major companies—airlines, big-box retailers, hospitality brands—are discussing how best to use Klout scores. Soon, he predicts, people with formidable Klout will board planes earlier, get free access to VIP airport lounges, stay in better hotel rooms, and receive deep discounts from retail stores and flash-sale outlets. “We say to brands that these are the people they should pay attention to most,” Thomson says. “How they want to do it is up to them.”

Not everyone is thrilled by the thought of a startup using a mysterious, proprietary algorithm to determine what kind of service, shopping discounts, or even job offers we might receive. The web teems with resentful blog posts about Klout, with titles like “Klout Has Gone Too Far,” “Why Your Klout Score Is Meaningless,” and “Delete Your Klout Profile Now!” Jaron Lanier, the social media skeptic and author of You Are Not a Gadget, hates the idea of Klout. “People’s lives are being run by stupid algorithms more and more,” Lanier says. “The only ones who escape it are the ones who avoid playing the game at all.” Peak outrage was achieved on October 26, when the company tweaked its algorithm and many people’s scores suddenly plummeted. To some, the jarring change made the whole concept of Klout seem capricious and meaningless, and they expressed their outrage in tweets, blog posts, and comments on the Klout website. “Not exactly fun having the Internet want to punch me in the face,” tweeted Klout CEO Joe Fernandez amid the uproar.

But not everyone wants to clock Fernandez. In fact, he appears to be at the forefront of a new and extremely promising online industry. Klout has received funding (a rumored $30 million of it) from venture capital behemoths like Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and Venrock. It’s facing down competitors like Kred and PeerIndex, racing to establish something akin to the Nielsen ratings for online social interactions. Klout may be ridiculed by those who find it obnoxious or silly or both, but it is aiming to become one of the pillars of social media.

Klout scores are compiled using proprietary algorithms that purport to quantify online influence. Size matters: Large followings on Twitter or Facebook can boost your rating. But it’s more important to have a high percentage of posts that are liked or retweeted. And just interacting with someone who has lots of Klout can jack up your score.

For a guy whose company seems to encourage loudmouthed self-promoters, Fernandez himself is remarkably soft-spoken and self-effacing. When I meet him in Klout’s offices, beneath a freeway overpass in San Francisco’s South of Market district, he flops down in an armchair, wearing a faded plaid shirt and a pair of raggedy sneakers. His hair is unkempt, his smile goofy, his manner friendly and open. He frequently asserts that Klout has succeeded only because he “hired people much smarter than me.”

Fernandez’s humility is key to his appeal. “If the CEO of Klout was a type-A guy, I think many of us would take offense when he talks about scoring us or judging us,” says David Pakman, a partner at Venrock. “But Joe’s not like that. He’s uniquely suited to this role.”

Fernandez got the idea for Klout in 2007, when at the age of 30 he had surgery to correct a jaw misalignment that had plagued him for years. Doctors wired his jaw shut for three months. “It was mentally and emotionally way tougher than I thought it would be,” Fernandez says. “I couldn’t talk to anyone. Even my mother couldn’t understand what I was saying.” He resorted to posting on the still-young Facebook and Twitter as his only means of communication. He posted his opinions on videogames, suggested neighborhoods to check out, and recommended restaurants—even though he wasn’t eating solid food. Every time a family member or friend responded to one of his updates, he relished his ability to sway their behavior. And as he looked over his feed he saw countless other people doing the same thing, recommending products or activities to an enthusiastic audience. Fernandez began to envision social media as an unprecedented eruption of opinions and micro-influence, a place where word-of-mouth recommendations—the most valuable kind—could spread farther and faster than ever before.

Fernandez’s vision was helped along by a series of biographical confluences. He had studied computer science at the University of Miami, going on to help run a pair of analytics companies—one in education, the other in real estate—that worked with massive, unwieldy streams of information. So he was familiar with the concept of finding patterns and value in large amounts of data. And as the child of a casino executive who specialized in herding rich South American gamblers into comped Caesars Palace suites, Fernandez saw up close and from a young age the power of free perks as a marketing tool.

With his jaw still clamped shut, recovering in his Lower East Side apartment, Fernandez opened an Excel file and began to enter data on everyone he was connected to on Facebook and Twitter: how many followers they had, how often they posted, how often others responded to or retweeted those posts. Some contacts (for instance, his young cousins) had hordes of Facebook friends but seemed to wield little overall influence. Others posted rarely, but their missives were consistently rebroadcast far and wide. He was building an algorithm that measured who sparked the most subsequent online actions. He sorted and re-sorted, weighing various metrics, looking at how they might shape results. Once he’d figured out a few basic principles, Fernandez hired a team of Singaporean coders to flesh out his ideas. Then, realizing the 13-hour time difference would impede their progress, he offshored himself. For four months, he lived in Singapore, sleeping on couches or in his programmers’ offices. On Christmas Eve of 2008, back in New York a year after his surgery, Fernandez launched Klout with a single tweet. By September 2009, he’d relocated to San Francisco to be closer to the social networking companies whose data Klout’s livelihood depends on. (His first offices were in the same building as Twitter headquarters.)

Fernandez says that he sees Klout as a form of empowerment for the little guy. Large companies have always attempted to woo influential people. It’s why starlets get showered with free clothes and athletes get paid to endorse sports drinks. It’s also why, once blogging took off, popular scribes like mommy blogger Dooce started receiving free washing machines. But Fernandez says that, until the dawn of social media, there was no way to pinpoint society’s hidden influencers. These include friends and family members whose recommendations directly impact our buying decisions, as well as quasi-public figures best known for their Twitter updates—like, say, San Francisco sommelier Rick Bakas, whose 71,000-plus followers hang on his every wine-pairing suggestion. “This is the democratization of influence,” says Mark Schaefer, an adjunct marketing professor at Rutgers and author of the book Return on Influence. “Suddenly regular people can carve out a niche by creating content that moves quickly through an engaged network. For brands, that’s buzz. And for the first time in history, we can measure it.”

Calvin Lee is a graphic designer in Los Angeles with a Klout score of 74. He has received 63 Klout perks, scoring freebies like a Windows phone, an invitation to a VH1 awards show, and a promotional hoodie for the movie Contraband. To keep his score up, Lee tweets up to 45 times a day—an average of one every 32 minutes. “People like food porn,” he notes, “so I try to post a lot of pictures of things I eat.”

Lee once took a vacation during which he had no access to the Internet. This made him uncomfortable. “I was worried that brands couldn’t get in touch with me. It’s easy for them to forget about you. And I knew my Klout score would go down if I stopped tweeting for too long.” When he was loaned an Audi A8 for a few days as a Klout perk, Lee knew exactly where he wanted to drive it. He road-tripped from LA up to San Francisco, eventually arriving at the Klout offices and shaking hands with Joe Fernandez. Naturally he tweeted and hashtagged the entire journey.

It’s easy to understand why marketers would want to reach maniacs like Lee. “We want to create powerful brand advocates,” says Tom Norwalk, president and CEO of the Seattle Convention and Visitors Bureau, who arranged a two-day, all-expenses-paid trip for 30 high-Klout visitors. “We hope these folks will tweet and Instagram to their many followers.” Virgin America has offered free flights, Capital One has dispensed bonus loyalty points, and Chevrolet has loaned out its new Sonic subcompact for long weekends.

But there’s more to the Klout score than a thirst for freebies. Throughout our lives, we are tagged with scores, some of them far more crucial to our well-being than anything Fernandez has handed out. Credit scores are maddeningly opaque and can be used against us in infinitely more harmful ways than a Klout score ever could. Our health records are used by huge organizations to segment and sift us behind closed doors. And yet there is something uniquely infuriating about the Klout score. “They’re calculating a Q score for everybody, and it turns out there’s a lot of emotion tied up in that,” Schaefer says. And the fact that Klout users’ status is so explicitly linked to material gain makes it an even more freighted situation, he says. “This is the intersection of self-loathing with brand opportunity.”

Almost immediately after Fernandez sent his Christmas Eve tweet debuting Klout—long before there were any perks to win or advantages to gain—the company was deluged with users just curious to see how they measured up. “I didn’t think about the ego component of having a number next to your name,” Fernandez says. When we see ourselves ranked, “we’re trained to want to grow that score.”

When I began researching this story, my own score was a mere 31. So I asked Klout product director Chris Makarsky how I might boost it. His first suggestion was to improve the “cadence” of my tweets. (For a moment, I thought he meant I should tweet in iambic pentameter. But he just meant that I should tweet a lot more.) Second, he pushed me to concentrate on one topic instead of spreading myself so thin. Third, he emphasized the importance of developing relationships with high-Klout people who might respond to my tweets, propagate them, and extend my influence to whole new population groups. Finally, he advised me to keep things upbeat. “We find that positive sentiment drives more action than negative,” he warned.

Using these tips, I managed to boost my Klout to 46 before it plateaued. From that point, I just couldn’t jolt the needle any higher. And, to my sheepish frustration, I wasn’t being offered any good perks (which seem to kick in when scores hit 50). It became clear that if I wanted more Klout, I’d need to game the system harder. I could glom on to influential Twitterati and connive to get retweeted by them. I could dramatically accelerate the frequency of my tweets, posting late into the night. And I could commit myself to never taking a break: Makarsky made it clear that a two-week vacation from social media might cause my score to nose-dive. The thought of running on this hamster wheel forever was positively exhausting, and it made me wonder whether Klout was really measuring my influence or just my ability to be relentless, to crowd-please, and to brown-nose. Consider that the only perfect 100 Klout score belongs to Justin Bieber, while President Obama’s score is currently at 91. We might not wish to glorify a metric that deems a teen pop star more influential than the leader of the free world.

In the depths of my personal bout with Klout status anxiety, I installed a browser plug-in that allows me to see the Klout scores of everyone in my Twitter feed. At first, I marveled at the folks with scores soaring up into the seventies and eighties. These were the “important” people—big media personalities and pundits with trillions of followers. But after a while I noticed that they seemed stuck in an echo chamber that was swirling with comments about the few headline topics of the social media moment, be it the best zinger at the recent GOP debate or that nutty New York Times story everybody read over the weekend.

Over time, I found my eyes drifting to tweets from folks with the lowest Klout scores. They talked about things nobody else was talking about. Sitcoms in Haiti. Quirky museum exhibits. Strange movie-theater lobby cards from the 1970s. The un-Kloutiest’s thoughts, jokes, and bubbles of honest emotion felt rawer, more authentic, and blissfully oblivious to the herd. Like unloved TV shows, these people had low Nielsen ratings—no brand would ever bother to advertise on their channels. And yet, these were the people I paid the most attention to. They were unique and genuine. That may not matter to marketers, and it may not win them much Klout. But it makes them a lot more interesting.

Just Because You're Not On Facebook ....

-

What can social networks on the internet know about persons who are friends of members, but have no user profile of their own? Researchers from the Interdisciplinary Center for Scientific Computing of Heidelberg University studied this question. Their work shows that through network analytical and machine learning tools the relationships between members and the connection patterns to non-members can be evaluated with regards to non-member relationships. Using simple contact data, it is possible, under certain conditions, to correctly predict that two non-members know each other with approx. 40 percent probability.

For several years scientists have been investigating what conclusions can be drawn from a computational analysis of input data by applying adequate learning and prediction algorithms. In a social network, information not disclosed by a member, such as sexual orientation or political preferences, can be "calculated" with a very high degree of accuracy if enough of his or her friends did provide such information about themselves. "Once confirmed friendships are known, predicting certain unknown properties is no longer that much of a challenge for machine learning," says Prof. Dr. Fred Hamprecht, co-founder of the Heidelberg Collaboratory for Image Processing (HCI). Until now, studies of this type were restricted to users of social networks, i.e. persons with a posted user profile who agreed to the given privacy terms. "Non-members, however, have no such agreement. We therefore studied their vulnerability to the automatic generation of so-called shadow profiles," explains Prof. Dr. Katharina Zweig, who until recently worked at the Interdisciplinary Center for Scientific Computing (IWR) of Heidelberg University.

In an online social network, it is possible to infer information about non-members, for instance by using so-called friend-finder applications. When new Facebook members register, they are asked to make available their full list of e-mail contacts, even of those people who are not Facebook members. "This very basic knowledge of who is acquainted with whom in the social network can be tied to information about who users know outside the network. In turn, this association can be used to deduce a substantial portion of relationships between non-members," explains Ágnes Horvát, who conducts research at the IWR.

To make their calculations, the Heidelberg researchers used a standard procedure of machine learning based on network analytical structural properties. As the data needed for the study was not freely obtainable, the researchers worked with anonymised real-world Facebook friendship networks as a test set of basic data. The partitioning between members and non-members was simulated using a broad possible range of models. These partitions were used to validate the study results. Using standard computers the researchers were able to calculate in just a few days which non-members were most likely friends of each other.

The Heidelberg scientists were astonished that all the simulation methods produced the same qualitative result. "Based on realistic assumptions about the percentage of a population that are members of a social network and the probability with which they will upload their e-mail address books, the calculations enabled us to accurately predict 40 percent of the relationships between non-members." According to Dr. Michael Hanselmann of the HCI, this represents a 20-fold improvement compared to simple guessing.

"Our investigation made clear the potential social networks have for inferring information about non-members. The results are also astonishing because they are based on mere contact data," emphasises Prof. Hamprecht. Many social network platforms, however, have far more data about users, such as age, income, education, or where they live. Using this data, a corresponding technical infrastructure and other structural properties of network analysis, the researchers believe that the prediction accuracy could be significantly improved. "Overall our project illustrates that we as a society have to come to an understanding about the extent to which relational data about persons who did not provide their consent may be used," says Prof. Zweig.

Why Is Everyone On The Internet So Angry?

-

With a presidential campaign, health care and the gun control debate in the news these days, one can't help getting sucked into the flame wars that are Internet comment threads. But psychologists say this addictive form of vitriolic back and forth should be avoided — or simply censored by online media outlets — because it actually damages society and mental health.

These days, online comments "are extraordinarily aggressive, without resolving anything," said Art Markman, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin. "At the end of it you can't possibly feel like anybody heard you. Having a strong emotional experience that doesn't resolve itself in any healthy way can't be a good thing."

If it's so unsatisfying and unhealthy, why do we do it?

A perfect storm of factors come together to engender the rudeness and aggression seen in the comments' sections of Web pages, Markman said. First, commenters are often virtually anonymous, and thus, unaccountable for their rudeness. Second, they are at a distance from the target of their anger — be it the article they're commenting on or another comment on that article — and people tend to antagonize distant abstractions more easily than living, breathing interlocutors. Third, it's easier to be nasty in writing than in speech, hence the now somewhat outmoded practice of leaving angry notes (back when people used paper), Markman said.

And because comment-section discourses don't happen in real time, commenters can write lengthy monologues, which tend to entrench them in their extreme viewpoint. "When you're having a conversation in person, who actually gets to deliver a monologue except people in the movies? Even if you get angry, people are talking back and forth and so eventually you have to calm down and listen so you can have a conversation," Markman told Life's Little Mysteries.

Chiming in on comment threads may even give one a feeling of accomplishment, albeit a false one. "There is so much going on in our lives that it is hard to find time to get out and physically help a cause, which makes 'armchair activism' an enticing [proposition]," a blogger at Daily Kos opined in a July 23 article.

And finally, Edward Wasserman, Knight Professor in Journalism Ethics at Washington and Lee University, noted another cause of the vitriol: bad examples set by the media. "Unfortunately, mainstream media have made a fortune teaching people the wrong ways to talk to each other, offering up Jerry Springer, Crossfire, Bill O'Reilly. People understandably conclude rage is the political vernacular, that this is how public ideas are talked about," Wasserman wrote in an article on his university's website. "It isn't."

Communication, the scholars say, is really about taking someone else's perspective, understanding it, and responding. "Tone of voice and gesture can have a large influence on your ability to understand what someone is saying," Markman said. "The further away from face-to-face, real-time dialogue you get, the harder it is to communicate."

In his opinion, media outlets should cut down on the anger and hatred that have become the norm in reader exchanges. "It's valuable to allow all sides of an argument to be heard. But it's not valuable for there to be personal attacks, or to have messages with an extremely angry tone. Even someone who is making a legitimate point but with an angry tone is hurting the nature of the argument, because they are promoting people to respond in kind," he said. "If on a website comments are left up that are making personal attacks in the nastiest way, you're sending the message that this is acceptable human behavior." [Niceness Is in Your DNA, Scientists Find]

For their part, people should seek out actual human beings to converse with, Markman said — and we should make a point of including a few people in our social circles who think differently from us. "You'll develop a healthy respect for people whose opinions differ from your own," he said.

Working out solutions to the kinds of hard problems that tend to garner the most comments online requires lengthy discussion and compromise. "The back-and-forth negotiation that goes on in having a conversation with someone you don't agree with is a skill," Markman said. And this skill is languishing, both among members of the public and our leaders.

Apple AirPlay and the Window of Obsolescence

-

Anytime there’s a new operating system, there’s somebody who complains. Usually, the new OS “breaks” some older piece of software. Or maybe your printer won’t work after the upgrade. Something.

“AirPlay does not seem to work on any of Apple’s computers much older than one year,” wrote one unhappy reader. “Please have a look at the sea of negative comments mentioning this on Apple’s pertinent upgrade download page. The negatives are a resounding thumbs down on this upgrade.”

Well, I’m not sure on that last point — three million people downloaded Mountain Lion in the first four days, a faster adoption than for any other Mac OS in history, and the users have given it a cumulative 4.5 out of 5 stars on the Mac App Store. But the grumbling is real.

AirPlay is a fairly amazing feature. As I described it, “AirPlay mirroring requires an Apple TV ($100), but lets you perform a real miracle: With one click, you can send whatever is on your Mac’s screen — sound and picture — to your TV. Wirelessly. You can send photo slide shows to the big screen. Or present lessons to a class. Or play online videos, including services like Hulu that aren’t available on the Apple TV alone.”

Only one problem: AirPlay requires a recent Mac — 2011 or newer. The reason, Apple says, is that AirPlay requires Intel’s QuickSync video compression hardware, which only the latest chips include. Apple lists the models it works on.

Now there are, fortunately, alternatives for older Macs (and older Mac OS X versions). You can read about one of them here. But that software is more complicated, and the video can be choppy.

So there we are: a new OS feature that requires certain hardware, and the Mac faithful are not pleased. Not pleased at all.

“So what we have here is decision by Apple to not support a key feature for the majority of their users, for seemingly the sole reason of pushing hardware upgrades,” wrote one reader. “Both of my Macs are under a year old but I have to wonder, what upcoming features will I lose out on in 18 months’ time? That isn’t a way to treat faithful fans (or any installed base), and makes the transition from Jobs to Cook look ominous to say the least.”

“10.8 is Apple’s most offensive slap at customer loyalty ever,” wrote another.

I appreciate that these readers are unhappy. But it’s not AirPlay that’s the problem. It’s not even Apple that’s the problem. (New software features that require certain hardware isn’t anything new. When Windows Vista came out, Media Center didn’t work unless you had a TV tuner card. The handwriting recognition in Windows works only on PCs’ touch screens. And so on.)

No, it’s the way the entire computer industry works.

When you look at it one way, the tech industry is about constant innovation, steady progress. Of course some things will become obsolete. Of course there will be new features that your older computer can’t exploit.

But if you look at it another way, the whole thing is a scam to make us keep buying new stuff over and over again. A new phone every two years. A new computer every four. Bad for our wallets, bad for the environment.

In AirPlay’s case, that window of “obsolescence,” if we’re calling it that, was supershort — one year. If you bought your Mac only two years ago, you can’t use AirPlay.

What should Apple have done, then? It had this great technology, finished and ready to ship. How could it have avoided this “slap at customer loyalty”? Should it have sat on AirPlay and not released it, to avoid that perception? If so, how long? Three years? Four years?

Or is the problem not with the tech companies, but with ourselves? Should we just accept that this is how the game is played? That when you buy a new computer, you should buy it for what it does now, and learn not to resent the fact that, inevitably, there will be better, faster, cheaper computers in the future?

It’s hard to imagine either of those approaches becoming satisfying, either to the industry players or their customers. So until there’s a resolution to this stalemate, the status quo will prevail: upgrade/grumble, upgrade/grumble. On this one, friends, there’s no solution in sight.

Google Eater Eggs

-

Google just got really awesome.

Awesome meaning you probably won’t get any more work done today because you’ll be playing Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon for the next four hours.

Here’s what you do: Go to Google and type “Bacon number” followed by the name of any actor.

See what happens? (Here’s a screenshot for everyone who’s too lazy to type. You’re welcome.)

It’s a so-called Easter egg — a hidden time-killing gem recently instigated by Google.

Google engineer Yossi Matias told the Hollywood Reporter that it’s an obvious example of how Google is able to pinpoint the connections between people.

“It’s interesting that this small-world phenomena when applied to the world of actors actually shows that in most cases, most actors aren’t that far apart from each other,” Matias told the Reporter. “And most of them have a relatively small Bacon number.”

Barack Obama’s “Bacon number” is just one. See if you can figure that out before typing it into Google.(see also The Oracle of Bacon)

Internet Pirates Will Always Win

-

STOPPING online piracy is like playing the world’s largest game of Whac-A-Mole.

Hit one, countless others appear. Quickly. And the mallet is heavy and slow.

Take as an example YouTube, where the Recording Industry Association of America almost rules with an iron fist, but doesn’t, because of deceptions like the one involving a cat.

YouTube, which is owned by Google, offers a free tool to the movie studios and television networks called Content ID. When a studio legitimately uploads a clip from a copyrighted film to YouTube, the Google tool automatically finds and blocks copies of the product.

To get around this roadblock, some YouTube users started placing copyrighted videos inside a still photo of a cat that appears to be watching an old JVC television set. The Content ID algorithm has a difficult time seeing that the video is violating any copyright rules; it just sees a cat watching TV.

Sure, it’s annoying for those who want to watch the video, but it works. (Obviously, it’s more than annoying for the company whose product is being pirated.)

Then there are those — possibly tens of millions of users, actually — who engage in peer-to-peer file-sharing on the sites using the BitTorrent protocol.

Earlier this year, after months of legal wrangling, authorities in a number of countries won an injunction against the Pirate Bay, probably the largest and most famous BitTorrent piracy site on the Web. The order blocked people from entering the site.

In retaliation, the Pirate Bay wrapped up the code that runs its entire Web site, and offered it as a free downloadable file for anyone to copy and install on their own servers. People began setting up hundreds of new versions of the site, and the piracy continues unabated.

Thus, whacking one big mole created hundreds of smaller ones.

Although the recording industries might believe they’re winning the fight, the Pirate Bay and others are continually one step ahead. In March, a Pirate Bay collaborator, who goes by the online name Mr. Spock, announced in a blog post that the team hoped to build drones that would float in the air and allow people to download movies and music through wireless radio transmitters.

“This way our machines will have to be shut down with aeroplanes in order to shut down the system,” Mr. Spock posted on the site. “A real act of war.” Some BitTorrent sites have also discussed storing servers in secure bank vaults. Message boards on the Web devoted to piracy have in the past raised the idea that the Pirate Bay has Web servers stored underwater.

“Piracy won’t go away,” said Ernesto Van Der Sar, editor of Torrent Freak, a site that reports on copyright and piracy news. “They’ve tried for years and they’ll keep on trying, but it won’t go away.” Mr. Van Der Sar said companies should stop trying to fight piracy and start experimenting with new ways to distribute content that is inevitably going to be pirated anyway.

According to Torrent Freak, the top pirated TV shows are downloaded several million times a week. Unauthorized movies, music, e-books, software, pornography, comics, photos and video games are watched, read and listened to via these piracy sites millions of times a day.

The copyright holders believe new laws will stop this type of piracy. But many others believe any laws will just push people to find creative new ways of getting the content they want.

“There’s a clearly established relationship between the legal availability of material online and copyright infringement; it’s an inverse relationship,” said Holmes Wilson, co-director of Fight for the Future, a nonprofit technology organization that is trying to stop new piracy laws from disrupting the Internet. “The most downloaded television shows on the Pirate Bay are the ones that are not legally available online.”

The hit HBO show “Game of Thrones” is a quintessential example of this. The show is sometimes downloaded illegally more times each week than it is watched on cable television. But even if HBO put the shows online, the price it could charge would still pale in comparison to the money it makes through cable operators. Mr. Wilson believes that the big media companies don’t really want to solve the piracy problem.

“If every TV show was offered at a fair price to everyone in the world, there would definitely be much less copyright infringement,” he said. “But because of the monopoly power of the cable companies and content creators, they might actually make less money.”

The way people download unauthorized content is changing. In the early days of music piracy, people transferred songs to their home or work computers. Now, with cloud-based sites, like Wuala, uTorrent and Tribler, people stream movies and music from third-party storage facilities, often to mobile devices and TV’s. Some of these cloud-based Web sites allow people to set up automatic downloads of new shows the moment they are uploaded to piracy sites. It’s like piracy-on-demand. And it will be much harder to trace and to stop.

It is only going to get worse. Piracy has started to move beyond the Internet and media and into the physical world. People on the fringes of tech, often early adopters of new devices and gadgets, are now working with 3-D printers that can churn out actual physical objects. Say you need a wall hook or want to replace a bit of hardware that fell off your luggage. You can download a file and “print” these objects with printers that spray layers of plastic, metal or ceramics into shapes.

And people are beginning to share files that contain the schematics for physical objects on these BitTorrent sites. Although 3-D printing is still in its infancy, it is soon expected to become as pervasive as illegal music downloading was in the late 1990s.

Content owners will find themselves stuck behind ancient legal walls when trying to stop people from downloading objects online as copyright laws do not apply to standard physical objects deemed “noncreative.”

In the arcade version of Whac-A-Mole, the game eventually ends — often when the player loses. In the piracy arms-race version, there doesn’t seem to be a conclusion. Sooner or later, the people who still believe they can hit the moles with their slow mallets might realize that their time would be better spent playing an entirely different game.

Passwords

-

Researchers examined 3.4 million PINs, all released in security breaches, to form a snapshot of the modern human psyche.

You’ve probably never asked yourself what your bank card PIN says about you, but the answer is “a lot”. There are 10,000 four-digit PIN combinations but researchers at DataGenetics, the data analysis firm, discovered that about 20 per cent of us use one of three. And more than half of those use a single one. Can you guess it? 1234. Followed by 1111 and 0000. If you’re wondering what this means about your personality, it’s this — that you’re staggeringly unoriginal (in your banking PIN) and probably not the type who goes in for burglar alarms.

Researchers trawled through 3.4 million PINs, all released in security breaches over the years, to uncover this data. The results form a snapshot of the modern human psyche. James Bond features as the 23rd most common with 0007, and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four inspired the PIN that comes in at 26th. Unsurprisingly, the snigger-worthy (if you’re 8) 6969 comes tenth.

The first puzzling passcode that the researchers encountered was 2580 at 22nd. It was only when making a phone call that one of them realised these are the numbers straight down the middle of a telephone keypad.

If you’ve chosen a year of birth or anniversary, you’re one of the crowd. Every combination of PINs starting with 19 is in the database’s top fifth.

And the least common PIN, used by only 25 people out of the 3.4 million? If your PIN is 8068, give yourself a pat on the back — you’re special. The rest of you, get to the bank and change yours.

Avatars

-

You could soon exist in a thousand places at once. So what would you all do – and what would it be like to meet a digital you?

One morning in Tokyo, Alex Schwartzkopf furrows his brow as he evaluates a grant proposal. At the same time, Alex Schwartzkopf is thousands of kilometres away in Virginia, chatting with a colleague. A knock at the door causes them to look up. Alex Schwartzkopf walks in.

Schwartzkopf is one of a small number of people who can be in more than one place at once and, in principle, do thousands of things at the same time. He and his colleagues at the US National Science Foundation have trained up a smart, animated, digital doppelgänger - mimicking everything from his professional knowledge to the way he moves his eyebrows - that can interact with people via a screen when he is not around. He can even talk to himself.

Many more people could soon be getting an idea of what it's like to have a double. It's becoming possible to create digital copies of ourselves to represent us when we can't be there in person. They can be programmed with your characteristics and preferences, are able to perform chores like updating social networks, and can even hold a conversation.

These autonomous identities are not duplicates of human beings in all their complexity, but simple and potentially useful personas. If they become more widespread, they could transform how people relate to each other and do business. They will save time, take onerous tasks out of our hands and perhaps even modify people's behaviour. So what would it be like to meet a digital you? And would you want to?

It might not feel like it, but technology has been acting autonomously on our behalf for quite a while. Answering machines and out-of-office email responders are rudimentary representatives. Limited as they are, these technologies obey explicit instructions to impersonate us to others.

One of the first attempts to take this impersonation a step further took place in the late 1990s at Xerox's labs in Palo Alto, California. Researchers were trying to create an animated quasi-intelligent persona, to live on a website. It would do things like talk to that person's virtual visitors and relay messages to and from them. But it was unsophisticated and certainly far from capable of intelligent conversation, says Tim Bickmore, of Northeastern University in Boston who worked on the project, so it was not commercialised.

The consensus has long been that the roadblock to creating a convincing persona is artificial intelligence. It still hasn't advanced sufficiently to reproduce complex human behaviour, and it would take years of training for an AI to resemble a person. Yet it has lately become clear that fully representing a human is unnecessary in today's digital environments. While we cannot program machines to think, getting them to do specific tasks is not a problem, says Joseph Paradiso, an engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Faceted identity

To understand why and where this could be useful, consider the way that a person's identity is represented on the internet. The typical user has a fragmented digital self, broken up into social media profiles, professional websites, comment boards, Twitter and so on. Of course, people have always presented themselves differently depending on context - be it the workplace or a bar - but Danah Boyd, a social media researcher at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, argues that digital communication enhances this because it inherently gives a narrow view of a person.

People manage these subsets of their identity like puppets, leaving them dormant when they're not needed. What researchers and companies have realised is that some of these puppets could be programmed to act autonomously. You don't need to copy a whole person, just a facet, and it doesn't require impressive AI and months of training.

For example, the website rep.licants.org, developed by artist Matthieu Cherubini, allows you to create a copy of your "social media self", which can take over Facebook and Twitter accounts when required. You prime it with data such as your location, age and topics that interest you, and it analyses what you've already posted on your various social networks. Armed with this knowledge, it then posts on your behalf.

In principle, such services could one day perform a similar job to the ghostwriters who manage the social media profiles of busy celebrities and politicians today. In fact, some people already automate their social media selves: some add-ons to a Twitter account can be programmed to send out messages such as a thank-you note if somebody follows you. As far as the recipients are concerned, the messages were sent by a real person.

Your professional persona can be replicated, too. The Australian company MyCyberTwin allows users to create copies of themselves that can engage visitors in a text conversation, accompanied by a photo or cartoon representation. These copies perform tasks such as answering questions about your work, like an interactive CV. "A single CyberTwin could be talking with millions of people at the same time," says John Zakos, who co-founded the firm. MyCyberTwin also uses tricks to add a touch of humanity. Users are asked to fill in a 30-question personality test, which means that the digital persona may act introverted or extroverted, for example.

In a few years, this simple persona could be extended to become an avatar - a visual animation of you. Avatars have long been associated with niche uses such as gaming or virtual worlds like Second Life, but there are signs that they could become more widespread. In the past year or two, Apple has filed a series of patents related to using animated avatars in social networking and video conferencing. Microsoft, too, is interested. It has been exploring how its Kinect motion-tracking device could map a user's face so it can be reproduced and animated digitally. The firm also plans to extend the avatars that millions of people use in its Xbox gaming system into Windows and the work environment.

So could avatars be automated too? It already happens in gaming: many people employ intelligent software to control their avatars when they're not around. For example, some World of Warcraft players program their avatars to fight for status or to farm gold.

To similar ends, in 2007 the National Science Foundation began Project Lifelike, an experiment to build an intelligent, animated avatar of Schwartzkopf, who at the time was a program director. The hope was to make the avatar good enough to train new employees.

Jason Leigh, a computer scientist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, used video capture of Schwartzkopf's face to create a dynamic, photorealistic animation. He also added a few characteristic quirks. For example, if Schwartkopf's copy was speaking intensely, his eyebrows would furrow, and he would occasionally chew his nails. "People's personal mannerisms are almost as distinguishing as their signature," Leigh says.

These tricks combined to make the copy seem more, well, human, which helped when Leigh introduced people to Schwartzkopf's doppelgänger. "They had a conversation with it as if it were a real person," he recalls. "Afterwards, they thanked it for the conversation."