Music Articles

1. Song Rights After 35 Years

2. Effect of Music

3. Reverse Abbey Road

4. Music As Therapy

5. Obsessives

6. Vinyl

7. Deconstructing The Who

8. Getting Rid of Earworms

9. The Internet

10. Rolling Stones at Glastonbury

11. Spotify

12. Spotify - the Royalty Payments

13. Mondegreens

14. Music and Generosity

15. Lively app to record concerts

16. Radio Caroline

17. Urinetown: The Musical

18. Spotify Stunt

19. Confusing Lyrics

20. Millions of Vinyls

21. Record Company Tricks

22. Taylor Swift and the Streaming Revolution

23. Radio Revolution

24. Kurzweil Samplers Win Grammy

25. $1000 LPs

26. Jackie Trent

27. Whistling

28. Learning With Music

29. Penny Lane

30. Piracy

31. Which Music Revolution?

32. Revolution 2

33. U2 Tour Budget

34. The Monkees

35. Who's In The Group?

36. Beatles Hits Without The Beatles

37. What Is Classic Rock?

38. John Berg

39. The Invention of Rock 'n' Roll

40. Enya

41. Bob Dylan Refs in Scientific Papers

42. Rockers and Mortality

43. The music industry

44. Songwriters

45. 1965 Article on the 'New Sound'

46. “Live Fast, Die Young.”

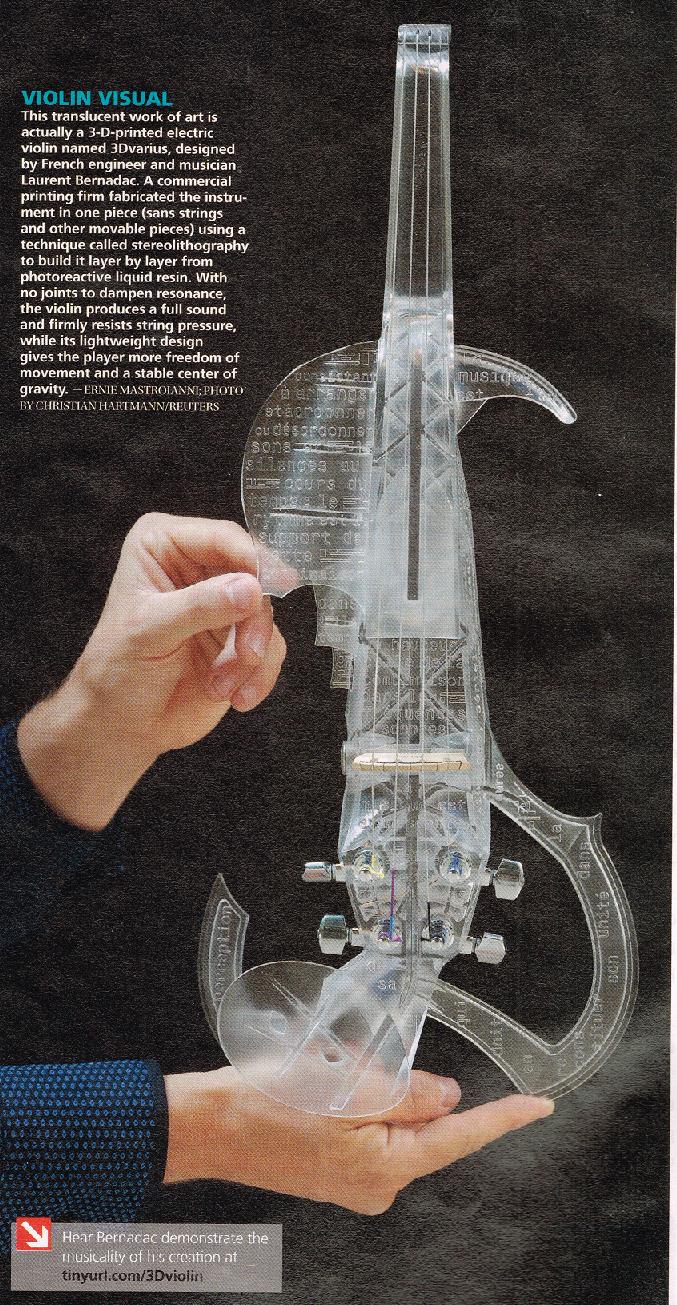

47. 3D Printed Violin

48. Prince Obituary (London Times)

49. Iron Maiden's 747

50. The Phonograph

51. David Bowie's Memphis furniture collection

The Rolling Stones 2020

Song Rights After 35 years

-

Since their release in 1978, hit albums like Bruce Springsteen's 'Darkness on the Edge of Town,' Billy Joel's '52nd Street,' the Doobie Brothers' 'Minute by Minute,' Kenny Rogers's 'Gambler' and Funkadelic's 'One Nation Under a Groove' have generated tens of millions of dollars for record companies. But thanks to a little-noted provision in United States copyright law, those artists - and thousands more - now have the right to reclaim ownership of their recordings, potentially leaving the labels out in the cold.

When copyright law was revised in the mid-1970s, musicians, like creators of other works of art, were granted 'termination rights, which allow them to regain control of their work after 35 years, so long as they apply at least two years in advance. Recordings from 1978 are the first to fall under the purview of the law, but in a matter of months, hits from 1979, like 'The Long Run' by the Eagles and 'Bad Girls' by Donna Summer, will be in the same situation - and then, as the calendar advances, every other master recording once it reaches the 35-year mark.

The provision also permits songwriters to reclaim ownership of qualifying songs. Bob Dylan has already filed to regain some of his compositions, as have other rock, pop and country performers like Tom Petty, Bryan Adams, Loretta Lynn, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Waits and Charlie Daniels, according to records on file at the United States Copyright Office.

"In terms of all those big acts you name, the recording industry has made a gazillion dollars on those masters, more than the artists have," said Don Henley, a founder both of the Eagles and the Recording Artists Coalition, which seeks to protect performers' legal rights. "So there's an issue of parity here, of fairness. This is a bone of contention, and it's going to get more contentious in the next couple of years."

With the recording industry already reeling from plummeting sales, termination rights claims could be another serious financial blow. Sales plunged to about $6.3 billion from $14.6 billion over the decade ending in 2009, in large part because of unauthorized downloading of music on the Internet, especially of new releases, which has left record labels disproportionately dependent on sales of older recordings in their catalogs.

"This is a life-threatening change for them, the legal equivalent of Internet technology," said Kenneth J. Abdo, a lawyer who leads a termination rights working group for the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences and has filed claims for some of his clients, who include Kool and the Gang. As a result the four major record companies - Universal, Sony BMG, EMI and Warner - have made it clear that they will not relinquish recordings they consider their property without a fight.

"We believe the termination right doesn't apply to most sound recordings," said Steven Marks, general counsel for the Recording Industry Association of America, a lobbying group in Washington that represents the interests of record labels. As the record companies see it, the master recordings belong to them in perpetuity, rather than to the artists who wrote and recorded the songs, because, the labels argue, the records are 'works for hire,' compilations created not by independent performers but by musicians who are, in essence, their employees.

Independent copyright experts, however, find that argument unconvincing. Not only have recording artists traditionally paid for the making of their records themselves, with advances from the record companies that are then charged against royalties, they are also exempted from both the obligations and benefits an employee typically expects.

"This is a situation where you have to use your own common sense," said June M. Besek, executive director of the Kernochan Center for Law, Media and the Arts at the Columbia University School of Law. "Where do they work? Do you pay Social Security for them? Do you withdraw taxes from a paycheck? Under those kinds of definitions it seems pretty clear that your standard kind of recording artist from the '70s or '80s is not an employee but an independent contractor."

Daryl Friedman, the Washington representative of the recording academy, which administers the Grammy Awards and is allied with the artists' position, expressed hope that negotiations could lead to a broad consensus in the artistic community, so there don't have to be 100 lawsuits. But with no such talks under way, lawyers predict that the termination rights dispute will have to be resolved in court.

"My gut feeling is that the issue could even make it to the Supreme Court," said Lita Rosario, an entertainment lawyer specializing in soul, funk and rap artists who has filed termination claims on behalf of clients, whom she declined to name. "Some lawyers and managers see this as an opportunity to go in and renegotiate a new and better deal. But I think there are going to be some artists who feel so strongly about this that they are not going to want to settle, and will insist on getting all their rights back."

So far the only significant ruling on the issue has been one in the record labels' favor. In that suit heirs of Jamaican reggae star Bob Marley, who died in 1981, sued Universal Music to regain control of and collect additional royalties on five of his albums, which included hits like 'Get Up, Stand Up' and 'One Love.'

But last September a federal district court in New York ruled that "each of the agreements provided that the sound recordings were the 'absolute property'" of the record company, and not Marley or his estate. That decision, however, applies only to Marley's pre-1978 recordings, which are governed by an earlier law that envisaged termination rights only in specific circumstances after 56 years, and it is being appealed.

Congress passed the copyright law in 1976, specifying that it would go into effect on Jan. 1, 1978, meaning that the earliest any recording can be reclaimed is Jan. 1, 2013. But artists must file termination notices at least two years before the date they want to recoup their work, and once a song or recording qualifies for termination, its authors have five years in which to file a claim; if they fail to act in that time, their right to reclaim the work lapses.

The legislation, however, fails to address several important issues. Do record producers, session musicians and studio engineers also qualify as 'authors' of a recording, entitled to a share of the rights after they revert? Can British groups like Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, and Dire Straits exercise termination rights on their American recordings, even if their original contract was signed in Britain? These issues too are also an important part of the quiet, behind-the-scenes struggle that is now going on.

Given the potentially huge amounts of money at stake and the delicacy of the issues, both record companies, and recording artists and their managers have been reticent in talking about termination rights. The four major record companies either declined to discuss the issue or did not respond to requests for comment, referring the matter to the industry association.

But a recording industry executive involved in the issue, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak for the labels, said that significant differences of opinion exist not only between the majors and smaller independent companies, but also among the big four, which has prevented them from taking a unified position. Some of the major labels, he said, favor a court battle, no matter how long or costly it might be, while others worry that taking an unyielding position could backfire if the case is lost, since musicians and songwriters would be so deeply alienated that they would refuse to negotiate new deals and insist on total control of all their recordings.

As for artists it is not clear how many have already filed claims to regain ownership of their recordings. Both Mr. Springsteen and Mr. Joel, who had two of the biggest hit albums of 1978, as well as their managers and legal advisers, declined to comment on their plans, and the United States Copyright Office said that, because termination rights claims are initially processed manually rather than electronically, its database is incomplete.

Songwriters, who in the past typically have had to share their rights with publishing companies, some of which are owned by or affiliated with record labels, have been more outspoken on the issue. As small independent operators to whom the work for hire argument is hard to apply, the balance of power seems to have tilted in their favor, especially if they are authors of songs that still have licensing potential for use on film and television soundtracks, as ringtones, or in commercials and video games.

"I've had the date circled in red for 35 years, and now it's time to move," said Rick Carnes, who is president of the Songwriters Guild of America and has written hits for country artists like Reba McEntire and Garth Brooks. "Year after year after year you are going to see more and more songs coming back to songwriters and having more and more influence on the market. We will own that music, and it’s still valuable."

In the absence of a definitive court ruling, some recording artists and their lawyers are talking about simply exercising their rights and daring the record companies to stop them. They complain that the labels in some cases are not responding to termination rights notices and predict that once 2013 arrives, a conflict that is now mostly hidden from view is likely to erupt in public.

"Right now this is kind of like a game of chicken, but with a shot clock," said Casey Rae-Hunter, deputy director of the Future of Music Coalition, which advocates for musicians and consumers. "Everyone is adopting a wait-and-see posture. But that can only be maintained for so long, because the clock is ticking."

Music has a fundamental affect on humans.

-

It can reduce stress, enhance relaxation, provide a distraction from pain, and improve the results of clinical therapy. New research published in BioMed Central's open access journal Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery demonstrates that music can reduce rejection of heart transplants in mice by influencing the immune system.

The link between the immune system and brain function is not clearly understood, nevertheless music is used clinically to reduce anxiety after heart attack, or to reduce pain and nausea during bone marrow transplantation. There is some evidence that music may act via the parasympathetic nervous system, which regulates the bodily functions that we have no conscious control over, including digestion.

Researchers from Japan investigated if music could influence the survival of heart transplants in mice. They found that opera and classical music both increased the time before the transplanted organs failed, but single frequency monotones and new age music did not.

The team led by Dr Masanori Niimi pinpointed the source of this protection to the spleen. Dr Uchiyama and Jin revealed, "Opera exposed mice had lower levels of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon gamma (IFN-γ). They also had increased levels of anti-inflammatory IL-4 and IL-10. Significantly these mice had increased numbers of CD4+CD25+ cells, which regulate the peripheral immune response."

It seems that music really does influence the immune system -- although the mechanism behind this still is not clear. Additionally, this study only looked at a limited selection of composers, so the effect of music on reducing organ rejection may not be limited to opera.

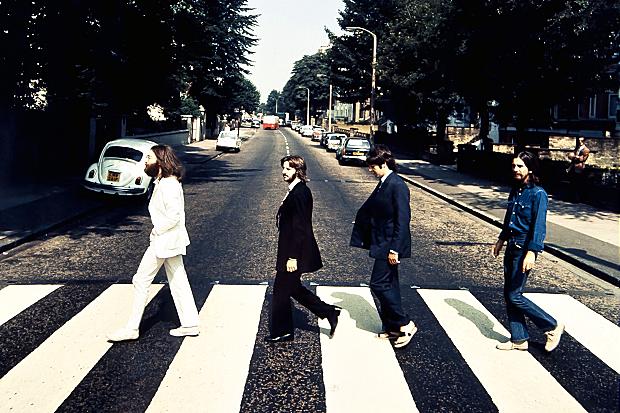

Reverse Abbey Road

A photograph of the Beatles walking "backwards" across Abbey Road has sold for £16,000 at auction, several thousand pounds more than expected. The photo was taken by the late Iain Macmillan, during the same shoot that resulted in the Fab Four's famous album cover.

A photograph of the Beatles walking "backwards" across Abbey Road has sold for £16,000 at auction, several thousand pounds more than expected. The photo was taken by the late Iain Macmillan, during the same shoot that resulted in the Fab Four's famous album cover.An unnamed buyer won the auction following a "frenzied bidding session" at Bloomsbury Auctions in London, on 22 May 2012. The rare item, one of six photos taken for Macmillan's shoot, reached almost twice the expected purchase price of £9,000.

Besides the direction of the Beatles' transit – and the purchase price – there's not much distinguishing the auctioned photograph from the official Abbey Road cover. But whereas Paul McCartney is barefoot on the LP cover, he wears sandals in this photograph. It is unknown what happened to his footwear in between.

Macmillan took the photos in just 10 minutes, standing on a ladder by the Abbey Road zebra crossing. Police were hired to stop traffic. "I think the reason [the photo] became so popular is its simplicity," Bloomsbury's Sarah Wheeler said last week. "It's a very simple, stylised shot, which people can relate to.".

Music As Therapy

-

When we first see Henry he is slumped in a wheelchair in a care home, his head down, his face expressionless. Then a member of staff puts headphones over his ears and tells him that they are going to play his music. A transformation takes place. Henry’s eyes open wide, he sings to himself and beats out the rhythm. His whole body becomes animated.

Later, he talks passionately and coherently about his musical tastes. It is as if a stimulant has been pumped into his brain, which in a sense is what has happened. Music is doing its miraculous work. The mesmerising YouTube clip of Henry has notched up 5.7 million views and alerted the world to something that those in the know have been aware of for many years — that music can have a profound effect on health and wellbeing.

From hospital foyers to operating theatres, from labour wards to care homes, music in all its forms is used to calm, to stimulate and to speed learning and recovery. It has been found to lower blood pressure and heart rate, to alter brain chemistry and levels of antibodies in the blood.

On a practical level, its effects can be extraordinary. When music from the Twenties and Thirties was played at mealtimes, care home residents ate more. Hip and knee replacement patients exposed to music and art needed less pain relief and left hospital a day earlier than those deprived of these stimuli.

According to Dr Claudius Conrad, the director of music in medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Mozart could save your life by reducing the need for sedation after surgery.

It is in dementia where the biggest strides have been made, from singing groups (see panel) to reminiscence singalongs and improvisation. Dr Trish Vella-Burrows, a music and health researcher at the Sidney De Haan Research Centre for Music, Arts and Health at Canterbury Christ Church University, says: “It’s a fantastic field to be working in now because the Government’s commitment to dementia care and the awareness that we need to reduce pharmacological interventions has coincided with a rise in community singing and music sweeping across the UK.

“At the same time we have more sophisticated tools for looking at the brain and the blood and working out what is happening. A study of amateur singers found raised levels of the hormone oxytocin, which helps to stimulate memory and social bonding.

“Brain scans show that the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that is highly stimulated when we make music together, is among the last to atrophy in many dementias. This may explain why music can elicit strong responses from people unable to communicate on any other level.”

Caroline Welsh, a flautist, witnesses this often though her work with Music for Life, a project run by Wigmore Hall and Dementia UK that sends leading musicians into care homes.

The residents selected to take part often show challenging behaviour that leads to their being isolated by staff and other residents. The aim is to encourage them to interact and show that a person remains — with a history and a personality.

The musicians visit for eight weekly sessions. “Once people lose language a whole range of things that matter to them cannot be discussed,” Welsh says. “They give up trying to communicate because it is too hard. But over the eight weeks we see people open up and try to communicate, and as they do they get more response from the musicians and staff. Because they feel somebody is trying to understand how they feel, they make more effort.”

Communication may not be verbal. “You can see changes in the way they sit, and move. They breathe more easily and show less agitation. One man, who spent most of the day in a state of great anxiety asking where the toilet was, always went straight to the music room on the right day without being prompted. Staff were amazed.”

Children with profound learning disabilities make up another group with whom music can be used as a communication tool. Felicity North, a senior therapist in the North West with the charity Nordoff Robbins, the UK’s largest private provider of music therapy, says: “At a non-verbal level, all the components of speech are present in music, including pitch, speed, phrasing and structure. Just as a baby vocalises and the mother repeats the sound, reflecting back what the child is doing, we can do that with music. We use music to work towards communication: some children may never actually develop speech.”

North encourages children to experiment. “They experience our understanding in a way that might be new for them. In time they learn about turn-taking, concentrating and imitating.”

The rewards of producing music can help profoundly disabled children to make choices and take chances. “You may have a child who has found it very difficult to hold anything. Then they become motivated to play an instrument with a beater and to hold it longer because they enjoy it. In time, they may be able to take a spoon and feed themselves.”

Mankind has probably been producing music longer than speech. Perhaps this explains why music can be used to calm and humanise the sterile settings of hospitals. Research at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital showed that music — sometimes in combination with visual art — reduced anxiety among new mothers, people receiving chemotherapy and patients being prepared for surgery.

Similar findings came from a study at John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, among patients who listened to recorded music while having surgery under local anaesthesia. According to Dr Hazim Sadideen, who led the study, “calmer patients may cope better with pain and recover quicker”.

Dr Conrad, a pianist, has found that playing the right music — notably Mozart — to patients in intensive care lowered their blood pressure and heart rate, and they needed fewer drugs. “Respiratory complications are a major killer of postoperative intensive care patients. The quicker they can come off a ventilator the more likely it is that they will survive,” he says. With fewer sedative drugs that can happen faster. “You could say that Mozart helps you survive.”

There’s little doubt that live music brings something extra to the party. The charity Live Music Now, founded more than 30 years ago by Yehudi Menuhin, works with young musicians in health settings. Trudy White, Live Music Now’s strategic director for health and wellbeing, says: “The power of music ... can be greatly intensified when played live by a skilled musician. The musician responds to the mood of the audience, creating connections that make those present feel valued. If live music is used appropriately, people may visit the doctor less and need less pain relief; care homes can be happier places and budgets could be saved.”

Melodies for the mind

Mary Jenkins has advanced dementia. She has very little speech and is cared for during her waking hours by her daughter, Pat Clements. Ask her what day of the week it is and she is unable to tell you. But every Wednesday she knows she is going singing. That is the day she attends the Alzheimer’s Society’s Singing for the Brain group, run by Pat near their homes in Whitchurch, Bristol. “I have no idea how she knows it’s a Wednesday,” Pat says. “But she gets quite excited. She has a good sense of rhythm and tells me when I am going too fast.

“It amazes me that even people with quite severe dementia seem to be able to recall music and enjoy it. They sing songs they knew when they were younger, but can also learn new ones and recall them the following week. “You can see the sense of relief come over them. Their shoulders go down and smiles come over their faces. Some carers tell me the people they look after are more content and stable for the rest of the day and into the next.”

Research carried out at the Sidney De Haan Research Centre shows that choral singing has a clear effect on wellbeing. The researchers have identified a number of benefits, including engendering happiness and countering depression; distracting from everyday worries; controlling breathing, which reduces anxiety; and offering social support, which combats isolation and loneliness.

David Phelops, who runs the 50-strong Harrow Community Choir — funded by Rethink Mental Illness and aimed at users of the mental health services — agrees. “Choir members tell me they are more focused, happier and more energetic.

“Some have gone on to develop their musical skills. One young man with paranoid schizophrenia has returned to his trumpet since joining the choir. Others have formed a band. Some have joined a singing and composition course run by Live Music Now and will bring what they’ve learnt back to the choir. “People can get lost in the fog of their illness and the drugs they take. They suffer a loss of confidence, stigma and fear. One man spent his first session in a corner mouthing the words. Within a year he was standing in front of the choir doing a solo.”

Obsessives

-

Men who collect multiple copies of same album

(story begins bottom right corner "It's a Numbers Game")

Vinyl

-

ONE common trend in many Western countries, regardless of the health of their recorded-music markets, is clear: vinyl is back. Sales of LPs were up in both Britain and Germany last year. In America vinyl sales are running 39% above last year's level (see chart). In Spain sales have risen from 16,000 in 2005 to 104,000 in 2010. That is an increase from a tiny base, but any rise in media sales in Spain's ravaged market is noteworthy.

This is a second revival for vinyl. The first, in the late 1990s, was driven largely by dance music. Teenagers bought Technics turntables and dreamed of becoming disc jockeys in Ibiza. But being a DJ is difficult and involves lugging heavy crates. Many have now gone over to laptops and memory sticks.

These days the most fervent vinyl enthusiasts are mostly after rock music. Chris Muratore of Nielsen, a research firm, says a little over half the top-selling vinyl albums in America this year have been releases by indie bands such as Bon Iver and Fleet Foxes. Last year's bestselling new vinyl album was “The Suburbs” by Arcade Fire. Most of the other records sold are reissues of classic albums. Those idiosyncratic baby-boomers who were persuaded to trade in their LPs for CDs 20 years ago are now being told to buy records once again.

What is going on? Oliver Goss of Record Pressing, a San Francisco vinyl factory, says it is a mixture of convenience and beauty. Many vinyl records come with codes for downloading the album from the internet, making them more convenient than CDs. And fans like having something large and heavy to hold in their hands. Some think that half the records sold are not actually played.

Vinyl has a distinction factor, too. “It is just cooler than a download,” explains Steve Redmond, a spokesman for Britain's annual Record Store Day. People used to buy bootleg CDs and Japanese imports containing music that none of their friends could get hold of. Now that almost every track is available free on music-streaming services like Spotify or on a pirate website, music fans need something else to boast about. That limited-edition 12-inch in translucent blue vinyl will do nicely.

Deconstructing Pete Townshend and The Who

-

Much of what we talked about that day in 1997 was connected to the Second World War, Townshend’s father’s generation and his own, and the postwar trauma that he saw as the driving force behind rock music. His father, Cliff, had been a saxophonist in the Royal Squadronaires, an Air Force band employed to entertain British troops at home and abroad. I knew this, but didn’t know how much it meant to the guitarist and songwriter for the Who, who seemed to me beyond, above, and dismissive of all that.

“Trauma is passed from generation to generation,” he said, waving his arms emphatically, his crossed legs bouncing. “I’ve unwittingly inherited what my father experienced.”

In his new memoir, “Who I Am,” Townshend elaborates in a voice that is calm, frank, and willfully exacting, like someone carefully extracting clarity from the past’s haze. “So many children had lived through terrible trauma in the immediate postwar years in Britain,” he writes, “that it was quite common to come across deeply confused young people. Shame led to secrecy; secrecy led to alienation. For me these feelings coalesced in a conviction that the collateral damage done to all of us who had grown up amid the aftermath of war had to be confronted and expressed in all popular art—not just literature, poetry or Picasso’s Guernica. Music, too. All good art cannot help but confront denial on its way to the truth.”

In retrospect, Townshend’s violent and somewhat awkward hotel-suite entry seems entirely apt. His onstage persona epitomized frustration writ large, with an array of shadowboxing gestures to compensate for inadequacies, perceived or real. His windmill style of slashing at his guitar strings signaled a failure to pick them fluidly, even if it made him shed blood and fingernails in the process (and it did). His scissor kicks and crouching leaps into the air merely brought him back down again, stomping on invisible enemies, or, as Townshend himself would write in one of his songs, “pounding stages like a clown.” He jumped, bounced, shook and swayed from side to side, but he never really danced, nothing so sexy or elegant for the gangly, slightly stooped and narrow-eyed guitar player with the impossibly large nose.

For Townshend, music is physical. As a child he was awakened by the late-night swing jam sessions of his father and friends, whose beats and crescendos thrilled even as they stole sleep. His devotion to a career in music was sealed while he was watching his father perform on stage. As a pre-teen seated next to two female fans, he overheard one of them gushing over his father’s sexual desirability.

Townshend would eventually tower over rock music, which he helped to create, successful in no small part because he smashed his instrument in an act of “auto-destructive art,” a concept championed by his former teacher, Gustav Metzger. But for Townshend, the guitar was not trashed, it was remade, transformed. “I haven’t smashed it,” he recalls in his memoir of his first unwitting stage act, prompted by a potentially embarrassing physical gesture that broke the guitar’s neck. “I’ve sculpted it for them…. I stumbled upon something more powerful than words, far more emotive than my white-boy attempts to play the blues.”

Visually, the members of the Who formed a kind of collective sculpted destruction. Their movements were tight, jerky, and erratic. Drummer Keith Moon, the inspiration for the character Animal in the Muppets, rocked in his seat, distended his arms, mouth agape as if he wanted to eat his drums whole. Singer Roger Daltrey stomped around in circles like an imprisoned convict, swinging his microphone (taped to its cable like a hockey-stick blade), wanting to hit someone hard, though only hinting at it, because he couldn’t, not in this jail. Bassist John Entwistle stood still but looked and sounded loud and angry, stewing in his corner.

And Townshend was in a fight. In his so-called “windmill” move, he could well be swinging a machete or turning a helicopter prop on its side. He leapt and slid on his knees across the stage, not in ecstasy, but in anger. He banged his guitar against his head, hating and hurting himself in equal parts, implicating the audience. At times, he strummed staccato hard and aimed his guitar at the audience, mowing them down with an aural machine gun.

It was never friendly or pretty. There were many rock stars singing about war, and the British experience of it in particular (Roger Waters and Pink Floyd adhered to this theme). But no one but Townshend and his band seemed in songs and onstage to be reenacting war, in all its rage, pathos, stupidity, and barbarism. “I was a yobbo [hooligan],” Townshend repeats throughout his book, “who desired respect and affirmation.”

I discovered Townshend’s music as a teen-ager. I soon realized that most of the rock music I’d liked before I heard him paled next to what he was producing. His music was demanding, you either listened to it or passed, because the music was played angrily, loudly, and menacingly, and then switched into passages of plaintive loneliness and humiliation. Several girls I was trying to woo hated it. Who wants to rock out and be humiliated?

If Led Zeppelin made you want to boogie, and the Rolling Stones and the Doors made you want sex, Townshend and the Who made you want to smash something up, maybe even yourself, and survive the assault. I didn’t understand the power of Townshend’s songs then, but now that I have known and spoken with him for several years, the map is clearer. Townshend was writing about the fallout from two world wars, and I’ve only experienced “war” as an abstraction. What would it mean, like Townsend in post-war England, to know that everyone you know has suffered and survived, but not without questions?

For Townshend, abstract suffering made his art sting—and, as is clear in our conversations and his memoir, he always wanted to make art with a capital “a.” This desire is equal parts plaintive and pathetic in his memoir. Older, consecrated artists like Leonard Bernstein grip him by the shoulders to tell him that his rock opera, “Tommy,” is momentous, a new form of art injecting blood into a tired medium. He nods appreciatively, and doesn’t believe them.

In the years since our first encounter in London, I have met Townshend on several occasions in New York and Tokyo. Each time, we have talked about war—what it means to him, and to me, twenty-plus years his junior. When I published my first book, “Japanamerica,” about the odd synchronicity between two societies, Japanese and American, at once at great odds and suddenly allies, my publisher asked me to send the book to Townshend. He had asked for it, why not give it to him? I was apprehensive. What if he didn’t like it, or worse, ignored it?

Instead he wrote the following: ”Japan’s holocaust was equally traumatic to the ones experienced by many Americans, and perhaps more sudden, more extreme and more focused. This story shows how today we all use movies, comics, music, art and advertising to face our past and its traumas, rather than to escape.” Now that I have read his memoir, I think what Townshend understood was my attempt to draw a parallel between what British musicians of his generation—beaten down by war, nuclear disaster, and identity crises—shared with Japanese artists, whose backgrounds and fierce artistry were shaped by the horrors of apocalypse, the bomb that can end everything as we know it. In contrast to all that was American whimsicality in the face of disaster. Japanese manga and anime artists created new visions out of the rubble of humiliation. They couldn’t fight, per se, but they could rattle the door and re-invent themselves, bursting through, tears and all.

Getting Rid of Earworms

-

They are the songs you cannot get out of your head. Now scientists may have found a way to help anyone plagued by those annoying tunes that lodge themselves inside our heads and repeat on an endless loop.

Researchers claim the best way to stopping the phenomenon, sometimes known as earworms – where snippets of a catchy song inexplicably play like a broken record in your brain – is to solve some tricky anagrams.

This can force the intrusive music out of your working memory, they say, allowing it to be replaced with other more amenable thoughts.

But they also warn not to try anything too difficult as those irritating melodies may wiggle their way back into your consciousness.

For those unwilling to carry around a book of anagrams, a good novel may also do the trick.

“The key is to find something that will give the right level of challenge,” said Dr Ira Hyman, a music psychologist at Western Washington University who conducted the research. “If you are cognitively engaged, it limits the ability of intrusive songs to enter your head.

“Something we can do automatically like driving or walking means you are not using all of your cognitive resource, so there is plenty of space left for that internal jukebox to start playing.

“Likewise, if you are trying something too hard, then your brain will not be engaged successfully, so that music can come back. You need to find that bit in the middle where there is not much space left in the brain. That will be different for each individual.

“It is like a Goldilocks effect – it can’t be too easy and it can’t be too hard, it has got to be just right.”

Dr Hyman and his team conducted a series of tests on volunteers by playing them popular songs in an attempt to find out how tunes can become stuck in long term memory.

By playing songs by the Beatles, Lady Gaga and Beyoncé while the volunteers completed mazes drawn out on pieces of paper, they found they could get songs to play mentally in the participants heads and that they were then likely to recur intrusively through the next day.

They then tested whether performing puzzles such as Sudoku or anagrams would help to reduce the recurrence of the earworms.

They found that while Sudoku puzzles could help prevent the songs from replaying their heads, if they were too difficult it had little effect.

Anagrams were more successful and they found that solving those with five letters gave the best results.

“Verbal tasks like solving anagrams or reading a good novel seem to be very good at keeping earworms out,” said Dr Hyman, who now hopes to examine whether similar techniques could be used to prevent other intrusive thoughts caused by anxiety or obsessiveness.

He added: “Music is relatively harmless but easy to start. Choruses tend to get stuck in your head because they are the bit we know best and because we don’t know the second or third verse, the song remains unfinished. Unfinished thoughts are more likely to return.”

Surveys by scientists have revealed a wide variety of songs tend to end up as earworms with three quarters of people reporting unique songs not experienced by others. The most common tend to be popular songs that are in the charts or are particularly well known.

Researchers, however, claim there is often little logic to the songs that become stuck in our heads but they often are songs we know well and like.

Dr Vicky Williamson, a music psychologist at Goldsmiths, University of London, has been studying earworms and says that the most likely songs to get stuck are those that are easy to hum along to or sing but are often unique to individuals. She has identified a number events that can trigger these songs to intrude on our every day lives, including repeated exposure to a piece of music, recent exposure to the music, seeing lyrics from the song, moments of stress and allowing your mind to wander.

She has been working with BBC6 Music to ask members of the public to identify their own stories involving earworms and is now attempting to identify new “cures” for those bothered by unwanted tunes.

Dr Williamson said: “Even reading a line in a newspaper can trigger the domino effect that starts a song running. During the trial of Michael Jackson’s doctor, we got a lot of people reporting Michael Jackson songs getting stuck in their head.

“Earworms seem to be the key to understanding how music gets so automatically connected in memory – we think we can use that. It could help alleviate people who are suffering from distressing thoughts.

“On learning we could help people suffering from cognitive decline, so if they can’t remember the stages to make a cup of tea, if you tech them it as a song, then they could make their own cup of tea rather than relying on other people.”

The Internet

-

It’s the weekend, Doctor Who’s back on TV and I’m doing a little time-travelling of my own. “God, this place is perfect,” says the boy, as we drive past the manicured cricket green and identikit cul-de-sacs of the small-town hell I grew up in. “I know,” I nod. “Can you imagine anywhere worse to be a teenager?”

That evening, back at my childhood home, we watch a BBC documentary about a dreamer from Bromley called David Jones, who wanted out of the suburbs so badly that he changed his name to Bowie, revolutionised pop music and ended up with a V&A exhibition in his honour. It reminded me of another broadcast I’d watched from the same armchair 15 years earlier. It was 1997, the 20th anniversary of the punk-rock wars. On my screen, face after battle-scarred face recalled how the limping pace of parish life had spurred them on to join the great youth uprising of 1977.

It was life-changing viewing. That same night I retreated to my bedroom to remodel my long, girly locks with a razor blade, and pen my own manifesto for getting out of Dodge — sorry, Dirge — City.

Fast-forward a decade and a half, and I’m getting the same swelling feelings of parochial frustration from watching the Bowie documentary. Only this time, instead of scurrying to my bedroom for another bout of hairdo terrorism, I reach for my iPad and merrily spend the rest of the evening swapping video clips of the Thin White Duke with the rest of the internet.

Until, fully sated, I fall asleep and wake up the next morning, not dreaming of trans-cultural anarchy, but worrying whether there is enough milk in the fridge for breakfast.

The internet has made me content. Even here, in the most mundane town in Britain, my wifi connection is all I need. Imagine having spent my teenage years like this — with the entire history of rock’n’roll at my fingertips and an endless online community of music fans to share it with. Blissful.

Too blissful, in fact. Because chances are, if that had been the case, I’d still be there now. Along with all the other dead-end shire kids who went on to use their restless energy for far more dramatic and creative ends than I ever managed.

Kids like the young David Jones. Would he have become David Bowie had he got broadband rather than a heavy dose of boredom and isolation for his 16th birthday? Or would he still be at home in Bromley, plugged into the Status Quo channel on YouTube and juggling a job in accounts? It’s a quantum-space problem too nightmarish to contemplate. One thing’s for sure: the boy was (almost) right: my small-town hell really was the perfect place to grow up. But especially 15 years ago, before the first internet router arrived.

Rolling Stones at Glastonbury

-

THE most famous lips in rock were sealed last week as the Rolling Stones prepared to take to the stage at Glastonbury.

Insiders revealed that Mick Jagger had rationed his speaking to no more than two hours a day and in no more than ten-minute bursts to preserve his voice for the big occasion.

The only public comments made by the 69-year-old, who sprays diluted Manuka honey and herbs into his mouth to lubricate his throat four hours before performing, were in an interview with the BBC’s John Humphrys recorded two weeks earlier.

A band insider said: “For him [Jagger] stopping talking has always worked best. It’s partly to do with the vocal cords, partly a calming technique.”

After 20 years of saying no to Glastonbury, the self-styled “greatest rock’n’roll band in the world” were leaving nothing to chance for their appearance last night.

As part of his preparations, Jagger applied at least three of his favourite Lift face masks (these are done at home) alternating with a £300 La Prairie Caviar facial — renowned for “intensive tightening and rejuvenation”.

Ironically, given that Michael Eavis, Glastonbury's creator, is a dairy farmer, Jagger also eschewed all dairy products for a week before the concert.

The singer spent weeks scrutinising videos of the headline acts for the previous four years to learn from their performances. The band’s road crew was pared down from the usual 200 to 50 but still included caterers, guitar engineers, sound and lighting technicians and Jagger’s masseur. There was, however, a large entourage of friends and family, including Jagger’s girlfriend L’Wren Scott, and the guitarist Ronnie Wood’s son, Jesse, who was with his partner Fearne Cotton, the broadcaster.

As part of their preparations, Wood and fellow guitarist Keith Richards spent hours running through the play list to cement their “running memory”, ensuring they could slip seamlessly from one song to the next, while Jagger spent months working with Torje Eike, a Norwegian fitness trainer. His gruelling fitness regime included running, kickboxing, cycling, gym work and ballet. In stark contrast, Richards told friends his main concern had been “making sure all my lighters have been filled”.

The band presented Glastonbury with one of the most eccentric and specific riders of its 43-year history, with requests for everything from Superglue (in case Ronnie Wood’s veneers drop out) to Richards’s regular request for HP sauce for his shepherd’s pie cooked to his own recipe by a member of the Four Seasons catering team who accompanied the band to Glastonbury.

Among Jagger’s requests were Prescriptives Super Flight Cream — noted for its superior moisturising properties for dehydrated skin — and a DAB radio (so Jagger could listen to the cricket). Meanwhile, Charlie Watts, the drummer, requested a “comfortable armchair” for his luxury yurt.

Jagger’s biggest concern, according to insiders, was the notoriously poor Glastonbury sound. He feared the Stones could end up sounding like a particularly ropey pub band.

After weeks of wrangling with the BBC over the rights to broadcast the performance (they finally bowed to allowing one hour of their set to be aired), the band had several meetings to discuss how to improve the sound quality. A Stones engineer was duly dispatched to the BBC’s outside location trucks to oversee sound mixes — costing the band thousands. And Richards came up with a guitar trick to deal with the vast sound on the night: he removed his low E string to create his instantly recognisable open G tuning. Glastonbury can be unpredictable for the legends of rock, with notable flops including U2. So the Stones took a big risk for a payment believed to be no more than £400,000. It was decades since they had earned so little for a concert.

But, as ever, they held a trump card. Plans are under way for a Stones DVD, tentatively titled 13 Stoned, which, although yet to be finalised, will probably include highlights from Glastonbury and their two Hyde Park concerts on July 6 and 13.

It will make them millions of pounds — so no matter what, the Stones will be the big winners from Glastonbury.

Spotify

-

It seems strange that just a few weeks after Pink Floyd relented and put their back catalogue on Spotify, Thom Yorke, of their spiritual heirs Radiohead, did the opposite, removing his records from the streaming service and tweeting: “Make no mistake, new artists you discover on Spotify will not get paid. Meanwhile shareholders will shortly be rolling in it. Simples.”

When I founded Saint Etienne in 1990, we pressed up white labels of 12in singles, put them in the car and sold them in London’s dance specialist record shops. It was reasonably lucrative but, more importantly, it meant we were written about. We were then offered a publishing deal from Warner/Chappell that was big enough for me and my bandmate Pete Wiggs to put down a deposit on a three-bedroom flat in Tufnell Park.

I was almost welling up as I wrote that paragraph. The industry has changed beyond all recognition. Publishing deals and record company advances like that don’t exist any more. Most people will buy music digitally, from iTunes — Apple, not the record companies, nor Spotify, and certainly not the artists, makes the lion’s share of money from music now.

Do they put it back in by saving historic venues,or supporting new talent? Not that I’ve noticed. They don’t have to take risks on advances for new acts, nor do they chance having piles of unsold stock in a warehouse. It’s an admirable business plan, the most successful in the history of the industry.

Yet, in spite of this, it is Spotify that is taking the heat. True, I don’t think I’ve ever had a cheque from Spotify, but even though Saint Etienne sold about 60,000 albums last year, the royalties I received from Apple weren’t enough to buy a second-hand Ford Fiesta.

A year ago I’d have suggested that a record should be available only as a physical product for the first six months, before going to iTunes and Spotify, rather like a film getting a cinema release ahead of the DVD. But Apple and others have thought of a way around this — most new laptops no longer have a disc drive, so you can’t add to your iTunes library from a CD. Nigel Godrich, the Radiohead producer, has said that “the music industry is being taken over by the back door”; in truth that happened more than a decade ago. Yorke and Godrich sound like a pair of medieval knights, and their anger has ancient precedents, in the 1930s when radio was seen as the enemy of record sales, and again in the 1940s when climbing record sales put live musicians out of work.

“We are just cutting our throats with this record business,” said James Petrillo, the musicians’ union leader, in 1942. “In New York music comes out of the walls and out of the ceiling all over town, but you never see a live musician ... we are scabbing on ourselves.” Strikes didn’t stop the way people consumed music then, and Yorke’s stand can’t change it now. The Spotify model is closer to radio than to digital downloads. With six million subscribers paying a maximum £10 a month, it isn’t surprising that Spotify’s royalties are tiny. But it helps younger listeners who have grown up with free music to discover new acts. This drives ticket sales, and a new talent will be paid for playing live or, if they get really big, on TV, in adverts and on film soundtracks. At which point this new talent could become rich and arrogant enough to thumb its nose at the industry, just like Thom Yorke.

Spotify - the Royalties

-

In June, David Lowery, singer-guitarist of Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven, posted part of a royalty statement to his blog The Trichordist. Cracker's song "Low," he revealed, had been played 1,159,000 times on Pandora in three months; Lowery, in his capacity as the song’s co-composer, was paid $16.89. For 116,280 plays on Spotify, Lowery got $12.05. Meanwhile, "Low" racked up only 18,797 plays on AM and FM radio stations during the same quarter. But for far fewer spins, Lowery received far more money: $1,373.78, to be exact.

Just last month, Thom Yorke of Radiohead and producer Nigel Godrich pulled their Atoms for Peace project off of Spotify, citing similar inequities in how music-streaming services pay artists. "Make no mistake new artists you discover on #Spotify will [not] get paid,” Yorke declared on Twitter. “[M]eanwhile shareholders will shortly [be] rolling in it. Simples."

Maybe. Or maybe it's not quite as simples as that. The image of wide-eyed young musicians having their lunches eaten by rapacious corporations is pretty compelling, and the ongoing collapse of the record business makes it look even scarier. The week ending July 28 had the lowest total album sales documented since Billboard started using Soundscan to track sales in 1991.

But it's also worth considering who's paying whom when music gets streamed, and how that might change. Whenever you read a shockingly low number and worry about the fate of your favorite band, it's worth keeping three things in mind.

1) "The music business" is not the same thing as "the recorded music business"—especially for musicians. A recent survey by the Future of Music Coalition found that, on average, 6 percent of musicians' income comes from sound recordings. That's not an insignificant amount, but it's also a lot less than what nonmusicians might guess. (And, although there isn't reliable data from the pre-Napster era, anecdotal evidence suggests that the percentage has never been much higher.) Recordings are how listeners generally spend the most time experiencing music, but not how we spend the most money experiencing music. In practice, recordings mostly serve as promotion for the other ways musicians make money: performing, most of all, but also salaries for playing in orchestras and other groups, session work, and so on.

2) Streaming music is not the digital equivalent of radio. For the most part, each time a song is played on ad-supported Pandora or subscription-based Spotify, it reaches one person. Each time a song is played on the radio, it can reach thousands of people—but when you turn on a radio station, you don't know what you're going to hear. Musicians expand their audience when new listeners stumble upon their work, which is why getting airplay is so important to them. Neither Pandora nor Spotify currently has anywhere near as many listeners as AM and FM radio—another reason it makes sense for them to pay less—but they also don't present the same kind of opportunities for discovering new music. Pandora lets you pick particular artists you like, so you'll hear them more often (although you might also discover similar artists you don't know already). Spotify lets you choose exactly what you want to hear from a near-infinite jukebox (although it has a "radio" setting, too). Meanwhile, iTunes Radio has appeared on the horizon.

3) "Paying to play a song" is not as simple as handing a performer a check. Sound recordings tend to be owned by record labels, which pay performers upfront against the possibility of future royalties. American radio stations don't have to pay anything to the copyright holders of the sound recordings they play. (In fact, payola scandals suggest that money tends to flow from copyright holders toward radio.) Spotify and Pandora, on the other hand, do have to pay rights-holders for permission to play particular recordings. (For more details on who pays whom, which rates are public, and how rates are determined, see this excellent essay by Jean Cook of the Future of Music Coalition.)

Spotify's on-demand service typically pays copyright owners something like half a cent per stream. That doesn't sound like much, but at the level of record labels that hold the rights to thousands of songs, it adds up. (During the week of release of Jay Z's Magna Carta … Holy Grail, Spotify streamed 14 million of its tracks. At that rate—and who knows if that's even close to the rate Jay gets—his label would have raked in $70,000 or so. He's good at math!)

Likewise, Pandora has taken pains to note that heavily streamed artists can make plenty of money through their service. Last October, co-founder Tim Westergren blogged that the company pays upward of $10,000 a year apiece for playing recordings by more than 2,000 artists. That's not saying that the artists will see that much money, naturally, since the rights-holders are the ones who get paid; for a label, though, $10,000 is like selling 1,000 CDs.

But then there's the question of publishing, which is what’s bugging Lowery—the way songwriters get paid. Performers benefit from having their recordings played that aren't directly monetary: glory, promotion, name recognition. Songwriters generally don't, so they get a rate determined by law when their work is purchased or played. Though middlemen such as performance rights agencies and publishing companies take their cut, somebody like Lowery can still see a significant trickle of money from co-writing a minor hit 20 years ago.

But the momentum of online streaming shows no signs of slowing—in the first half of this year, it was up 24 percent from last year—and that's why songwriters are worried. Statutory publishing rates for streaming audio are currently low enough that the amount Pandora lays out for publishing amounts to only 4 percent of its annual revenue, or less than one-hundredth of a cent per stream, according to this editorial by two members of Congress. Pandora's hoping to lower that rate even further; earlier this summer, the members of Pink Floyd wrote an indignant USA Today opinion piece about Pandora's shady maneuvering. (It didn’t mention that the band had released its catalogue to Spotify a week or so earlier.)

There are plenty of high-profile holdouts whose music isn't on Spotify: AC/DC, Tool, Garth Brooks, Led Zeppelin, the Beatles—all artists for whom Spotify arguably can't do much good anyway. Nobody's going to hear the Beatles' music for the first time and fall in love with it by stumbling onto somebody's Spotify playlist, and Led Zep doesn't need to convince young music fans to come see them play live. But the rates Spotify pays to the kind of big names that attract subscribers are often much higher, as Sasha Frere-Jones notes.

At the other end of the scale, there are some independent labels (like the Chicago-based indie-rock label Drag City) and artists who have opted out of Spotify, which, as Thom Yorke correctly observed, doesn't generally pay them much anyway. English singer-songwriter Sam Duckworth complained last month that 4,685 plays on Spotify netted him a bit under 20 pounds, "the equivalent to me selling two albums at a show ... I think it's fair to say that at least two of those almost 5,000 listeners would have bought the album from me if they knew the financial disparity from streaming."

That might well be the case. If we're getting into hypotheticals, though, how many of those listeners might have bought the album, or come to one of Duckworth's shows, because they heard the stream and were impressed by what they heard? And how does that compare to what would have happened if one of Duckworth's songs had been broadcast once on the radio and heard by 4,685 people? More broadly, when does it make financial sense for musicians to restrict access to their recordings, and when is it simply a matter of asserting more control over their art?

There's no way to know the answers to those questions, but Nigel Godrich's explanation that pulling Atoms for Peace's recordings from Spotify was "about standing up for other artists' rights" doesn't entirely hold water. For less-than-famous performers, recording royalties have never been a way to get rich, or even to make a living; they're a way to build up enough of a reputation to make a living through other means, and maybe accrue a little bit of cash. It's songwriters—whether or not they're performers too—who need to be wary about what's going to happen as radio and recording sales gradually give way to streaming.

Mondegreens

-

If you ever sang along to David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust with the words “Making love to a Seagull” rather than “ego” you may like to know that the Wellcome Trust has given £60,000 to the Clerks choral ensemble to explore the science behind misheard lyrics. The research aims to help our understanding of music perception among the hearing-impaired.

The project, Tales from Babel: Musical Adventures in the Science of Hearing, will see the choral ensemble testing audiences across the UK on why they are able to follow some lyrics and texts in music but mishear others.

Edward Wickham, director of The Clerks, said audience members will use electronic handsets to record which words they can hear when the six-strong group sings different lines simultaneously.

As part of the project, the Wellcome Trust conducted a survey into what lyrics are often misheard. As well as the Bowie’s “ego” to “seagull” lyric, there was also “You’re gonna be the one at Sainsbury’s” instead of “You’re gonna be the one that saves me” for the song Wonderwall by Oasis.

The Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds has the line “A girl with kaleidoscope eyes” which was often misheard as “The girl with colitis walks by”.

Other examples included “Dance then, wherever you may be; I am The Lord of the dance settee” from the popular hymn Lord of the Dance by English songwriter Sydney Carter, and “Your voice is soft like submarine” instead of “summer rain” from Jolene by Dolly Parton.

The technical term for misheard lyrics is “mondegreen”, after a famous mishearing of the words “laid him on the green” as “Lady Mondegreen” in a Scottish ballad.

Music and Generosity

-

Tipping in a restaurant isn’t just about the quality of the service. Customers give bigger tips to waiters who compliment them on their food choice and men give bigger tips to waitresses who wear make-up. But our generosity can also be increased by the right song lyrics or briefest message on the check.

In Europe especially, tipping is more optional than it is in the US and often runs to 5-10% rather than the 15-20% expected in the US. Celine Jacob et al tested the influence of the music played during lunch at a busy French restaurant. Two music CDs, each with 15 songs, were prepared. One CD had songs judged to have ‘prosocial’ lyrics while the other had neutral lyrics. These popular French songs were first selected by 281 passers-by and then rated by 95 undergraduate students. Customers listening to the prosocial lyrics left bigger tips.

Just how these prosocial songs affect us has been studied by Greitmeyer et al who tested the effect of songs with prosocial lyrics on the helpfulness of German students. If you’re wondering, as I did, what kinds of songs made the prosocial category, the English songs on Greitmeyer’s list included Michael Jackson’s ‘Heal the World’, Live Aid’s ‘Feed the world’ and, somewhat curiously I thought, ‘Help’ by the Beatles. These were contrasted with the socially neutral Jackson’s ‘On the line’ and the Beatles’ ‘Octopuses Garden’. These tracks might not be top of everyone’s playlist (I doubt that any amount of Michael Jackson would make my husband feel helpful) but as always these songs had been pretested for their power to bring out the prosocial in us. Of the 34 German students who listened to selected tracks, those who listened to the prosocial songs went on to show more empathy, co-operation and helping behaviour. This suggests that the customers in Celine Jacob’s French restaurant left bigger tips because the prosocial songs made them fell more empathic and helpful to the waiting staff.

But how do we know it was the lyrics and not, say the tempo or style of the tracks? Celine Jacob recently tested this by swapping song lyrics for written quotes on the customer’s bill (or check, as our US cousins call it). Five waitresses recorded customer behaviour, including tipping, over weekday lunch hours. Some customer bills carried the altruistic quote ‘A good turn never goes amiss’ from the French writer George Sand. Others had the Latin proverb: ‘He who writes reads twice’, and the remainder had no quote.

The quotes were first given to 20 passers-by who then rated their own level of altruism. Those who had read Sand’s quote were left feeling significantly more altruistic than those who read the Latin proverb. Back in the restaurant, customers, regardless of sex, who got the altruistic quote, gave bigger tips more often than those with the neutral quote or no quote at all.

What struck me was how easily our behaviour can be influenced by such a small, barely noticed message. Think of all the messages that we experience throughout the day, from jingles to bumper stickers. Our motives are constantly being manipulated and we are usually completely unaware that this is happening. As for dining Chez Ragsdale, I’m thinking of making my own dinner playlist.

Lively app records concerts

-

The hordes of music fans going to see bands this week at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Tex., can relive the concerts a couple of ways. They can make recordings of dubious quality using their smartphones.

Or, if they’re willing to spend a few bucks, they can get audio straight from the sound board at the concerts and, in some cases, professionally shot video by downloading an app called Lively. Some of the music is even free.

The app is from a new Seattle start-up, which is using the festival as a way to get wider exposure for a service it wants to make as essential to a touring band’s toolkit as microphones and amplifiers. The idea behind the Lively service is to give bands another way to make revenue while touring, without forcing them to become technology wizards.

To offer their recordings through the Lively app, bands simply need an iPad with an audio management app from Lively and an inexpensive piece of hardware for plugging into soundboards at concert venues. Lively is getting some venues to set this gear up permanently. For some concerts, it sets up three-camera shoots to create videos of the performances.

Lively clears song rights issues with music publishers. Bands can then put audio and video recordings of their concerts up for sale — $4.99 for audio; $9.99 for video and audio is standard — soon after the concerts happened. About half of the bands that use Lively choose to make their music free to fans. Lively takes a 30 percent cut of the sale, with artists taking the rest.

The idea for Lively came to Dean Graziano, the company’s founder and chief executive, in 2012 when he was at a concert in Seattle and witnessed a common, irksome sight: a sea of fans staring at the smartphones in front of their faces, rather than at the performers on stage.

“I saw 20,000 people with phones in the air and said this is lose-lose for everybody,” said Mr. Graziano in a recent interview in Lively’s loft-like office in an industrial neighborhood in Seattle, outfitted with performance spaces for visiting musicians.

Fans were pirating the concerts, most likely without even realizing it, he said. The performers, meanwhile, were missing out on an opportunity to make money from their fans with much higher quality recordings.

Lively’s service is getting more uptake at this point from up-and-coming bands, rather than the headliners selling out stadiums and giant amphitheaters. A few bigger names, however, have begun using the service, including the Pixies and Keith Urban.

At South by Southwest, Lively expects to providing recordings for more than 100 bands. By the end of the summer, the service expects to have more than 500 hours worth of live shows, said Mr. Graziano.

Radio Caroline

-

If you can remember the 1960s, so it is said (in a remark attributed variously to Dennis Hopper, George Harrison, Robin Williams and Grace Slick), you weren’t there. Actually, the exact opposite is the case. The decade is venerated precisely because so many people can remember it so well. They thus feel, as did Wordsworth about the early French Revolution: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/To be young was very heaven.”

Central to this misty-eyed vision of the 1960s is Radio Caroline, which next week — how the years fly by when we’re having fun — celebrates its first half-century. It launched on air on March 29, 1964, when the achingly glamorous Simon Dee said these words: “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. This is Radio Caroline on 199, your all-day music station.”

Supposedly named after President Kennedy’s daughter, Caroline was the first of Britain’s pirate radio stations. Operating in international waters, generally in converted trawlers or abandoned wartime forts on the North Sea, they unleashed all-day pop on a music-starved country, which until then had had to rely either on Radio Luxembourg (dire reception and evenings only, with the airtime sponsored by big record companies as a platform for their own artists) or the Light Programme (which confined the dangerous irreverence of pop and rock to a few hours a week).

In breaking this stranglehold, Caroline’s founder, a young Irish music promoter called Ronan O’Rahilly, who had been unable to get Georgie Fame any airtime, was following a family tradition of resistance to authority. He launched the station on an Easter Sunday because his grandfather, shot by the English in Dublin in 1916, was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising.

In a country now saturated with music, via radio, iTunes, Spotify, Deezer, Napster, MySpace, Blinkbox and YouTube, it is hard to convey just what a sensation Caroline was. Within a month, it was getting 2,000 letters a day; MPs were in uproar; and its advertising was used by the Duke of Bedford to bring visitors to Woburn Abbey. By autumn, it had more listeners than the three BBC stations put together. It nurtured groovy young DJs such as Tony Blackburn, Johnnie Walker, Emperor Rosko, DLT and Roger Gale, who showed how hip he was by becoming a Tory MP.

Most important, Caroline and the other pirates led directly to the birth of Radio 1, which launched the month after the pirates became illegal. It was Tony Benn who, as Labour’s postmaster-general, threw them off the air — and not the Tories, as depicted in Richard Curtis’s film The Boat That Rocked.

In some form or another, in different places on sea and inland, Caroline has mostly been broadcasting ever since. Today, online only, it operates from a studio in Kent, a 24-hour classic-album station run by volunteers and funded entirely by listeners. A campaign to get it on medium wave has come to nothing. But it is still here, and celebrating its 50th birthday. The first record it ever played was the Rolling Stones’ Not Fade Away, which certainly turned out to be prophetic.

Urinetown

-

Urinetown? Are they taking the piss? But no, it’s no good, all the best pee puns and wee jokes have been made. Some of them are in the show itself. Even the title is a pun (You’re In Town). We will just have to take it seriously, for it is at bottom a fundamentally serious piece.

Urinetown started life on the New York fringe in 1999, went on to Broadway, where it ran for three years and won three Tonys, and now arrives over here, directed by Jamie Lloyd. It’s an extended lavatory joke that’s also a satire on American corporate capitalism, which is hardly a daring or original target — what about the operations of Chinese state capitalism in Africa, for a change? Still, when global corporations seem increasingly unlikely to pay tax, while claiming ownership of earth, water and air, and even patenting genes, Urinetown still has a point.

Caldwell B Cladwell is head of UGC (Urine Good Company) and sports a scary moustache. There’s been a drought for the past 20 years, the reservoirs have dried up, but UGC has come to the rescue with a brilliant plan: it collects the public’s urine, recycles it as drinking water and limits everyone’s daily allowance. Everyone’s? Well, mostly the poor’s. But such enlightened green policies also require some pretty dictatorial laws and curbs on liberty, as we are discovering in the real world. It is now illegal to pee anywhere except in a “public amenity” — owned by UGC, of course — and, what’s more, you have to pay for the privilege. Don’t pay, don’t pee. UGC is becoming richer and richer, the public more and more desperate.

Meanwhile, there’s Cladwell’s daughter Hope, a bit of an ingénue. After a kindly explanation from her father about UGC’s benevolence, she exclaims: “Gosh, I never realised large monopolising corporations could be such a force for good in the world!” But after witnessing a confrontation between the brutal, corrupt police and the heroic, handsome lavatory attendant Bobby Strong, she starts to wonder. Bobby has become radicalised after his poor old dad was caught short and ended up being sent off to the penal colony of Urinetown — a place from which no one has ever returned...

There are scenes that hover on the edge of tiresome silliness, but some amusing jokes, too, the best delivered by Jonathan Slinger as the horrible Officer Lockstock, with his customary creepy, gloating grin. Often they’re jokes about the show itself. “Nothing can kill a show like too much exposition,” he explains near the start. “How about bad subject matter?” asks Little Sally (Karis Jack), a wide-eyed Dickensian street child. “Or a bad title?” There’s also a rare olfactory joke here, with the auditorium lightly spritzed at intervals with some horrible approximation of pine-scented air freshener, of the kind favoured by unlicensed minicab drivers.

Eventually, Bobby leads the people in revolt against UGC and their utterly corrupt political cronies, bearing banners with slogans such as “Free to Pee!” and “Power to the Peeple!”. Then the show darkens, with some genuinely unpleasant stage brutality that wipes the smile from our faces completely. As a song’n’dance satire, Urinetown is not that funny. The lyrics, by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis, aren’t clever or biting enough, the musical parodies aren’t overblown enough — it’s not even rude and bawdy enough. (The childish mind, ie mine, will immediately want to know: yes, but what about everybody’s poo?) Its ropy fringe origins are too obvious, despite talents such as Slinger and Lloyd, Soutra Gilmour’s powerful industrial-nightmare set and Ann Yee’s excellent choreography.

The ending, though, is grimly satisfying. The ultimate villains of the piece aren’t the CEOs and the megacorps. Because who actually used up all the water? Us. We did. As with every other environmental problem or disaster now facing us, there are seven billion perpetrators and, cleverly playing dual roles, seven billion victims. Little Sally wants to know why this musical can’t have a happy ending. Because, says Officer Lockstock, it’s not that kind of show. Life isn’t like that.

As an extended satirical lavatory joke, Urinetown hardly compares with, say, Jonathan Swift’s The Benefit of Farting Explained; as a water drama, it isn’t An Enemy of the People, and I’d hesitate to say “Urine for a treat”. But it’s certainly different.

Spotify Stunt

-

Spotify, the Swedish streaming service that looks primed for an IPO, has divided the music industry for years.

+ Vociferous detractors like Radiohead’s Thom Yorke (who had an imaginative description for the service last year) and David Byrne of Talking Heads fame have criticized the penny-pinching royalties it pays; supporters like Billy Bragg and the Eurythmics Dave Stewart (who said musicians should “worship” Spotify) say resistance is futile. The six million consumers who pay $10 a month for the premium version of the service are obviously fans.

+ Regardless, this week Vulfpeck, a funk band based in Michigan, thinks it has cleverly figured out a way to make Spotify pay the bills: by recording an album of complete silence and getting people to stream it while they sleep.

+ In this YouTube post Vulfpeck’s frontman Jack Stratton claims that for each Spotify user that streams “Sleepify”—which is comprised of ten tracks of complete silence—on repeat throughout the night, the band will make $4. If enough people do it, that could help it fund a free tour, which Stratton claims will visit the cities that stream the album the most.

+ So has Vulfpeck unearthed a new threat to the Spotify business model? Probably not. A spokesman for Spotify describes it as a “clever stunt” and confirms the company’s “artist services team” has already been in touch with the band. He said there are no plans to crack down on silent music.

+ Last year, Spotify paid out $500 million in royalties (70% percent of its gross revenues) and detailed typical monthly payments to artists in the following chart.

+ So, even in the unlikely event that Sleepify were to become a global hit, it wouldn’t break the bank. Whether other artists jump on the silence bandwagon remains to be seen.

+ Of course, Vulfpeck are not the first to record silent music. Composer John Cage is known for his use of silence, while Sonic Youth’s 63 second noiseless composition “Silence” was actually suspended from sale on iTunes for a while.

Confusing Lyrics

-

Eggmen, distrustful elephants and plenty of jambo jumbo feature among the most confounding lyrics of all time, according to a survey.

The research, which asked 2,000 people to rank the song words they find most confusing, singles out Lionel Richie, the Beatles, the Killers, Michael Jackson and Oasis.

A third of respondents said that Brandon Flowers of the Killers had baffled them with the words to Human, from the 2008 album Day and Age. In it, the frontman apparently deliberately decides to dispense with proper grammar in a reference to a quote from Hunter S. Thompson, the late drugaddled journalist.

The chorus involves Flowers posing the indecipherable question: “Are we human, or are we dancer?” The singer later states that he is on his knees begging for the answer.

Martin Cloonan, an expert in pop music at Glasgow University, said: “[He] has admitted that the line is taken from a Hunter S. Thompson quote, ‘We’re raising a nation of dancers’. Flowers said, ‘I say that it’s a mild social statement, and that’s all I’m gonna say’.”

In close second with 27 per cent was a line from I Am the Walrus, in which John Lennon points out: “I am the eggman, they are the eggmen, I am the walrus, goo goo g’ joob.”

Professor Cloonan said: “John Lennon spoke of writing some of this while on an acid trip, which might help explain things. It is an exercise in surrealism and wordplay. Lennon did once declare [in the song Glass Onion] that ‘the Walrus was Paul’ but it appears to in fact be a reference to Lewis Carroll’s The Walrus and the Carpenter and so, a reference to surreal or imaginary worlds.”

Among an array of eccentric achievements, Michael Jackson asked the world: “What about elephants? Have we lost their trust?” in Earth Song. Nearly 20 per cent of those surveyed put this in their top three.

“Ultimately this is a misjudged protest song,” Professor Cloonan said. “[It] sees a world in which the innocent simply have things done to them by malevolent forces. It could be construed as an attack on the ivory trade.”

In fourth place was the lyric “tom bol li de se de moi ya, hey jambo jumbo” in the song All Night Long by Lionel Richie, who admitted that the lyrics were “a wonderful joke”. He originally intended to use an African dialect that could not be fitted to the rhythm, so instead he made the words up.

Carly Rae Jepson may not be well-known, but her song Call Me Maybe is. In it she states: “Before you came into my life, I missed you so bad.” Professor Cloonan said: “You really can miss something you’ve never had . . . it is about having something, rather than an actual person, missing in your life — a fairly common experience.”

Polling surprisingly low was Champagne Supernova, written by Noel Gallagher of Oasis. He admitted the lyric “slowly walking down the hall, faster than a cannonball” was written when he couldn’t think of anything else that rhymed with “hall”.

Millions of Vinyls

-

Paul Mawhinney, a former music-store owner in Pittsburgh, spent more than 40 years amassing a collection of some three million LPs and 45s, many of them bargain-bin rejects that had been thoroughly forgotten. The world’s indifference, he believed, made even the most neglected records precious: music that hadn’t been transferred to digital files would vanish forever unless someone bought his collection and preserved it.

Mawhinney spent about two decades trying to find someone who agreed. He struck a deal for $28.5 million in the late 1990s with the Internet retailer CDNow, he says, but the sale of his collection fell through when the dot-com bubble started to quiver. He contacted the Library of Congress, but negotiations fizzled. In 2008 he auctioned the collection on eBay for $3,002,150, but the winning bidder turned out to be an unsuspecting Irishman who said his account had been hacked.

Then last year, a friend of Mawhinney’s pointed him toward a classified ad in the back of Billboard magazine:

RECORD COLLECTIONS. We BUY any record collection. Any style of music. We pay HIGHER prices than anyone else.

That fall, eight empty semitrailers, each 53 feet long, arrived outside Mawhinney’s warehouse in Pittsburgh. The convoy left, heavy with vinyl. Mawhinney never met the buyer.