Religion Articles

1. God didn't make man; man made gods

2. The Church of Copy and Paste

3. Keep Religion Out Of Private Life

4. The Atheist Manifesto

5. Christianity In Crisis

6. The Jerusalem Syndrome

7. The Daily Show

8. Absolutist Morality

9. Nuns On The Frontier

10. Bishops' World

11. Is Free Will An Illusion?

12. Why Cults Are Mindless

13. The Catholic Church and Money

14. God Loves Misery

15. God's Fanatics Are Back

16. The Problem With Hell

17. Creationist Education

18. Science vs Religion

19. 5 Misconceptions About OT

20. Doomsday Thinking

21. The Decline of Evangelical America

22. Why Priests Quit

23. Atheist Church

24. What Atheists Can Learn From Religion

25. Organ Donors and Religion

26. Fundies

27. Heaven or Hallucinations?

28. Violent Fanatics

29. Autistic children are atheists

30. William Lane Craig

31. Christian Atheism

32. Conservatives Try To Deal With Gay Marriage

33. Fundamentalists and Scholarship

34. Superman and Saints

35. Churches Always Lag Behind

36. Magical Thinking

37. Tax Churches

38. Trans Genders

39. Evangelicals and End Times

40. Why Noah's Ark Is Unpossible

41. When did the church accept that the Earth moves around the sun?

42. Beliefs Always Trump Facts

43. The Problem With Religious Rules

44. Richard Dawkins

45. Matthew Parris on Richard Dawkins

46. Britain: Religion and the Law

47. What They Do, Not What They Believe

48. Scientology

49. Separation of Church and State

50. Declining Evangelicalism and Crystal Cathedral

51. What Is The Religious Argument Against Atheism?

52. Atheist Survived Tornado

53. Cargo Cults - More Than Meets The Eye

54. The Lessons of the Flood Stories

55. DIY

56. Why is it so hard for Christians to understand evolution?

57. Richard Dawkins Interview

58. Dating The New Testament Sources

59. When Can Society Overrule Religions?

60. The Religious Right and Birth Control

61. Bill Gates On Religion

62. Noah and Fundamentalists

63. Mormon Teaching

64. What Is A 'Christian' Nation?

65. 11 reasons why Jesus is not coming back...

66. Biblical Marriage

67. The Onion: 9/11 Hijackers In Hell

68. Old Earth Is Heresy

69. Losing Religion

70. Religious Apathy

71. Religious Extremism

72. Catholics and Contraceptives

73. Tea Party Is A Religious Movement

74. Glasshouses - Publicity Killing Churches

75. Intolerance

76. Bible Literalists

77. The Church of War

78. Tribes (Seth Godin)

79. Surrogacy To Split The Religious Right

80. A Game for Good Christians

81. Exodus - a myth

82. Religion and The Rich In America

83. God and Philosophy

84. Cain and Abel and Justice

85. Leaving Closed Communities

86. Evangelicals and Pop Culture

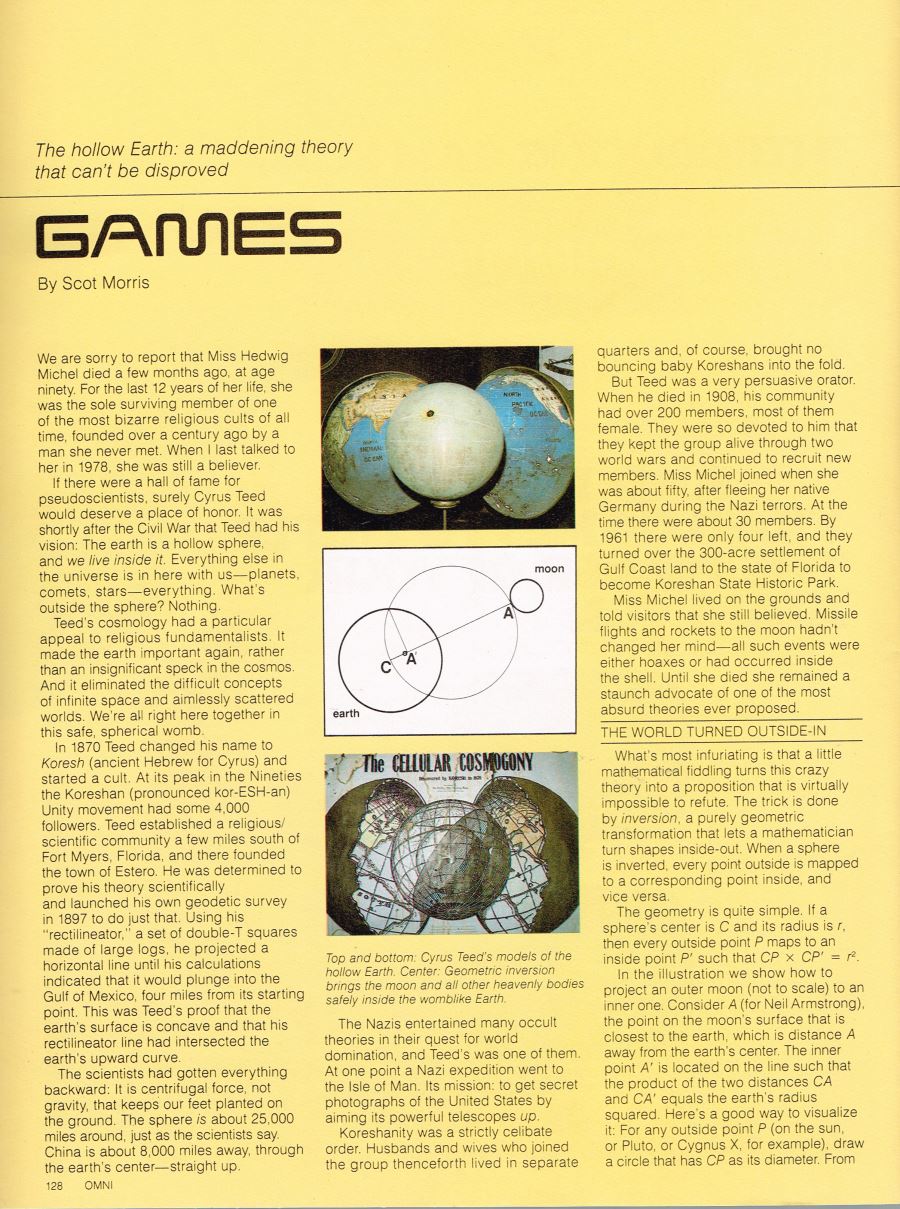

87. Crackpot But Irrefutable

88. Did Jesus Save The Klingons?

89. Jerusalem

90. Adam and Eve

91. Religious Fatties

92. Religions Will Die Out

93. Pope Francis and Doorways

94. Religion Is No Sacred Cow

95. Scientology

96. Religious Exemptions

97. Offending Religions

98. The Violence of Religious Reformations

99. Evangelicals For Israel

100. How Scientology Fights Critics

101. Sabbath Rules Kills Kids

102. Zodiac Signs Out Of Whack

103. Scientology Losing Control

104. (Pro) Wrestling and Religion (They're both fake)

105. Neil deGrasse Tyson

106. Religion Based Bigotry

107. Heaven Visit Literature

108. The Patriarchy and The Role of Women

109. Hard-Wired For Supernatural Explanations?

110. Conservatives think there's a global war against Xity

111. Miracle-Busting Science

112. Irish Catholic Church

113. Questioning Mohammed

114. Christian Terrorists

115. The First Church of Cannabis

116. Christians are just too gullible

117. Why Christians Feel Persecuted

118. Kim Davis and Need For Militant Atheism

119. Searching For Meaning

120. Disappearing Middle East Religions

121. The War On Religion

122. Why Radical Islam Appeals

123. Christians and Porn

124. Evangelicals and Trump

125. 8 ways the religious right wins converts – to atheism

126. Trashing The Brand

127. Christian Pseudo-Science

128. Fundamentalists, Evangelicals, Pentecostals

2. The Church of Copy and Paste

3. Keep Religion Out Of Private Life

4. The Atheist Manifesto

5. Christianity In Crisis

6. The Jerusalem Syndrome

7. The Daily Show

8. Absolutist Morality

9. Nuns On The Frontier

10. Bishops' World

11. Is Free Will An Illusion?

12. Why Cults Are Mindless

13. The Catholic Church and Money

14. God Loves Misery

15. God's Fanatics Are Back

16. The Problem With Hell

17. Creationist Education

18. Science vs Religion

19. 5 Misconceptions About OT

20. Doomsday Thinking

21. The Decline of Evangelical America

22. Why Priests Quit

23. Atheist Church

24. What Atheists Can Learn From Religion

25. Organ Donors and Religion

26. Fundies

27. Heaven or Hallucinations?

28. Violent Fanatics

29. Autistic children are atheists

30. William Lane Craig

31. Christian Atheism

32. Conservatives Try To Deal With Gay Marriage

33. Fundamentalists and Scholarship

34. Superman and Saints

35. Churches Always Lag Behind

36. Magical Thinking

37. Tax Churches

38. Trans Genders

39. Evangelicals and End Times

40. Why Noah's Ark Is Unpossible

41. When did the church accept that the Earth moves around the sun?

42. Beliefs Always Trump Facts

43. The Problem With Religious Rules

44. Richard Dawkins

45. Matthew Parris on Richard Dawkins

46. Britain: Religion and the Law

47. What They Do, Not What They Believe

48. Scientology

49. Separation of Church and State

50. Declining Evangelicalism and Crystal Cathedral

51. What Is The Religious Argument Against Atheism?

52. Atheist Survived Tornado

53. Cargo Cults - More Than Meets The Eye

54. The Lessons of the Flood Stories

55. DIY

56. Why is it so hard for Christians to understand evolution?

57. Richard Dawkins Interview

58. Dating The New Testament Sources

59. When Can Society Overrule Religions?

60. The Religious Right and Birth Control

61. Bill Gates On Religion

62. Noah and Fundamentalists

63. Mormon Teaching

64. What Is A 'Christian' Nation?

65. 11 reasons why Jesus is not coming back...

66. Biblical Marriage

67. The Onion: 9/11 Hijackers In Hell

68. Old Earth Is Heresy

69. Losing Religion

70. Religious Apathy

71. Religious Extremism

72. Catholics and Contraceptives

73. Tea Party Is A Religious Movement

74. Glasshouses - Publicity Killing Churches

75. Intolerance

76. Bible Literalists

77. The Church of War

78. Tribes (Seth Godin)

79. Surrogacy To Split The Religious Right

80. A Game for Good Christians

81. Exodus - a myth

82. Religion and The Rich In America

83. God and Philosophy

84. Cain and Abel and Justice

85. Leaving Closed Communities

86. Evangelicals and Pop Culture

87. Crackpot But Irrefutable

88. Did Jesus Save The Klingons?

89. Jerusalem

90. Adam and Eve

91. Religious Fatties

92. Religions Will Die Out

93. Pope Francis and Doorways

94. Religion Is No Sacred Cow

95. Scientology

96. Religious Exemptions

97. Offending Religions

98. The Violence of Religious Reformations

99. Evangelicals For Israel

100. How Scientology Fights Critics

101. Sabbath Rules Kills Kids

102. Zodiac Signs Out Of Whack

103. Scientology Losing Control

104. (Pro) Wrestling and Religion (They're both fake)

105. Neil deGrasse Tyson

106. Religion Based Bigotry

107. Heaven Visit Literature

108. The Patriarchy and The Role of Women

109. Hard-Wired For Supernatural Explanations?

110. Conservatives think there's a global war against Xity

111. Miracle-Busting Science

112. Irish Catholic Church

113. Questioning Mohammed

114. Christian Terrorists

115. The First Church of Cannabis

116. Christians are just too gullible

117. Why Christians Feel Persecuted

118. Kim Davis and Need For Militant Atheism

119. Searching For Meaning

120. Disappearing Middle East Religions

121. The War On Religion

122. Why Radical Islam Appeals

123. Christians and Porn

124. Evangelicals and Trump

125. 8 ways the religious right wins converts – to atheism

126. Trashing The Brand

127. Christian Pseudo-Science

128. Fundamentalists, Evangelicals, Pentecostals

-

See also Mind articles on how our brains refuse to accept facts that contradict our world view

God didn't make man; man made gods

-

In recent years scientists specializing in the mind have begun to unravel religion's "DNA."

Before John Lennon imagined "living life in peace," he conjured "no heaven .. / no hell below us ../ and no religion too."

No religion: What was Lennon summoning? For starters, a world without "divine" messengers, like Osama bin Laden, sparking violence. A world where mistakes, like the avoidable loss of life in Hurricane Katrina, would be rectified rather than chalked up to "God's will." Where politicians no longer compete to prove who believes more strongly in the irrational and untenable. Where critical thinking is an ideal. In short, a world that makes sense.

In recent years scientists specializing in the mind have begun to unravel religion's "DNA." They have produced robust theories, backed by empirical evidence (including "imaging" studies of the brain at work), that support the conclusion that it was humans who created God, not the other way around. And the better we understand the science, the closer we can come to "no heaven .. no hell .. and no religion too." Like our physiological DNA, the psychological mechanisms behind faith evolved over the eons through natural selection. They helped our ancestors work effectively in small groups and survive and reproduce, traits developed long before recorded history, from foundations deep in our mammalian, primate and African hunter-gatherer past.

For example, we are born with a powerful need for attachment, identified as long ago as the 1940s by psychiatrist John Bowlby and expanded on by psychologist Mary Ainsworth. Individual survival was enhanced by protectors, beginning with our mothers. Attachment is reinforced physiologically through brain chemistry, and we evolved and retain neural networks completely dedicated to it. We easily expand that inborn need for protectors to authority figures of any sort, including religious leaders and, more saliently, gods. God becomes a super parent, able to protect us and care for us even when our more corporeal support systems disappear, through death or distance.

Scientists have so far identified about 20 hard-wired, evolved "adaptations" as the building blocks of religion. Like attachment, they are mechanisms that underlie human interactions: Brain-imaging studies at the National Institutes of Health showed that when test subjects were read statements about religion and asked to agree or disagree, the same brain networks that process human social behavior - our ability to negotiate relationships with others - were engaged.

Among the psychological adaptations related to religion are our need for reciprocity, our tendency to attribute unknown events to human agency, our capacity for romantic love, our fierce "out-group" hatreds and just as fierce loyalties to the in groups of kin and allies. Religion hijacks these traits. The rivalry between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, for example, or the doctrinal battles between Protestant and Catholic reflect our "groupish" tendencies.

In addition to these adaptations, humans have developed the remarkable ability to think about what goes on in other people's minds and create and rehearse complex interactions with an unseen other. In our minds we can de-couple cognition from time, place and circumstance. We consider what someone else might do in our place; we project future scenarios; we replay past events. It's an easy jump to say, conversing with the dead or to conjuring gods and praying to them.

Morality, which some see as imposed by gods or religion on savage humans, science sees as yet another adaptive strategy handed down to us by natural selection.

Yale psychology professor Paul Bloom notes that "it is often beneficial for humans to work together ... which means it would have been adaptive to evaluate the niceness and nastiness of other individuals." In groundbreaking research, he and his team found that infants in their first year of life demonstrate aspects of an innate sense of right and wrong, good and bad, even fair and unfair. When shown a puppet climbing a mountain, either helped or hindered by a second puppet, the babies oriented toward the helpful puppet. They were able to make an evaluative social judgment, in a sense a moral response.

Michael Tomasello, a developmental psychologist who co-directs the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, has also done work related to morality and very young children. He and his colleagues have produced a wealth of research that demonstrates children's capacities for altruism. He argues that we are born altruists who then have to learn strategic self-interest.

Beyond psychological adaptations and mechanisms, scientists have discovered neurological explanations for what many interpret as evidence of divine existence. Canadian psychologist Michael Persinger, who developed what he calls a "god helmet" that blocks sight and sound but stimulates the brain's temporal lobe, notes that many of his helmeted research subjects reported feeling the presence of "another." Depending on their personal and cultural history, they then interpreted the sensed presence as either a supernatural or religious figure. It is conceivable that St. Paul's dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus was, in reality, a seizure caused by temporal lobe epilepsy.

The better we understand human psychology and neurology, the more we will uncover the underpinnings of religion. Some of them, like the attachment system, push us toward a belief in gods and make departing from it extraordinarily difficult. But it is possible.

We can be better as a species if we recognize religion as a man-made construct. We owe it to ourselves to at least consider the real roots of religious belief, so we can deal with life as it is, taking advantage of perhaps our mind's greatest adaptation: our ability to use reason.

Imagine that.

The Church of Copy and Paste

-

The First Church of Pirate Bay

The city of Uppsala has seen its share of religious congregations. In ancient times, it was the main pagan center of Sweden, famed for its temple to the Old Norse gods. In the Middle Ages, it became a Christian stronghold. Today, Uppsala is home to Isak Gerson, a bright, polite, twenty-year-old philosophy student and the spiritual leader of the Missionary Church of Kopimism, which last week became Sweden's newest registered religion.

Modern Sweden isn't known as a particularly religious place: in a recent poll, only seventeen per cent of Swedes said that faith is an important part of their lives. But Sweden is known, in recent years, as a hotbed of online piracy and anti-copyright activism. That's the tradition from which Kopimism arises.

The religion's history goes something like this: In 2001, a lobby group called the Antipiratbyran - the Anti-Piracy Bureau - was formed in Sweden to combat copyright infringement. In 2003, members of a growing free-information movement copied the lobby group's name, but removed the 'anti,' calling themselves Piratbyran - the Piracy Bureau. Later that same year, Piratbyran created a Web site called The Pirate Bay, which quickly became the world's most notorious source for downloading feature films, TV shows, and software.

In 2005, Ibrahim Botani, a Kurdish immigrant to Sweden and a central figure in Piratbyran, designed a kind of un-copyright logo called 'kopimi' (pronounced 'copy me'). Adding the kopimi mark to a work of intellectual property indicates that you not only give permission for it to be copied but actively encourage it.

After Botani died unexpectedly, in 2010, Piratbyran decided to disband. But The Pirate Bay still thrives, despite an ongoing criminal case against its operators. And in 2006, Rick Falkvinge founded Sweden's Pirate Party, a political party that runs on a pro-Internet platform, with special emphasis on copyright and patent reform. Gerson is an active member: "I've been managing local campaigns for the election," he told me. "And I've been working a lot with the Young Pirates Association - the youth wing of the Party."

The Missionary Church of Kopimism picks up where Piratbyran left off: it has taken the values of Swedish Pirate movement and codified them into a religion. They call their central sacrament 'kopyacting,' wherein believers copy information in communion with each other, most always online, and especially via file-sharing. Ibi Botani's kopimi mark - a stylized 'k' inside a pyramid - is their religious symbol, as are CTRL+C and CTRL+V. Where Christian clergy might sign a letter "yours in Christ," Kopimists write, "Copy and seed." They have no god.

"We see the world as built on copies," Gerson told me. "We often talk about originality; we don't believe there's any such thing. It's certainly that way with life - most parts of the world, from DNA to manufacturing, are built by copying." The highest form of worship, he said, is the remix: "You use other people's works to make something better."

Fittingly, it was exactly this kind of collaborative spirit that led to the founding of the Missionary Church of Kopimism. In a blog post last week, Peter Sunde, one of the founders of The Pirate Bay, suggested that Kopimism as a religion had originated from a comment made by one of its opponents. Several years ago, he wrote, a Swedish lawyer for the M.P.A.A. was asked about file-sharing advocates. She replied, "It's just a few people, very loud. They're a cult. They call themselves Kopimists." Sunde thought this cult business sounded like a good idea, and looked into registering Kopimism as a religion, but never followed through. Gerson did. "This is one of the essential things with how the internet and kopimism works," Sunde wrote. "If you don't do it, someone else will."

In Sweden, the separation of church and state became law on January 1, 2000, the day that the Lutheran Church of Sweden stopped being the official state church. Since then, a government agency called the Kammarkollegiet has accepted applications for the legal recognition of religions. "They don't make any kind of assessment of what the beliefs are, and the association is not sanctioned by the state," Anders Backstrom, a professor of the sociology of religion at Uppsala University, told me. But the recognition of Kopimism, he said, is "a new situation. We haven't seen anything of its kind before."

The most comparable previous effort was in 2008, when Carlos Bebeacua, a Uruguayan artist living in Sweden, attempted to register the Church of the Madonna of the Orgasm. The Kammarkollegiet refused his application, and in 2010 the Administrative Court of Appeal upheld the rejection, arguing that the 'madonna' (but not the 'orgasm') part of the church's name would "cause offense not only in the broad groups of the population that have Christian roots, but also in society as a whole."

Kopimism apparently raised no such qualms. Or maybe the Kopimists are just better than the Orgasmists at filling out government paperwork. "It's exactly the same process as registering a business company," Professor Backstrom said. But he thinks it's unlikely that Kopimism's success will inspire a flood of new applications. "In Sweden, we have many small New Age groups, but most of them have made no effort to be recognized," he said. "Being recognized might mean they are opened to government scrutiny."

For the Missionary Church of Kopimism, which holds up privacy as one of its chief values, such scrutiny could be a big problem, and it's not clear what they'll gain from registration. "We don't really get any formal rights or benefits," Gerson said. "We can apply for the right to marry people. There is government aid we can apply for, but we have no such plans today. I don't, at least." Rick Falkvinge, the Pirate Party founder, speculated that if the Church incorporated the seal of confession into its rites, members could take advantage of the confidentiality that comes with certain privileged conversations. Generally, though, Sweden offers few legal exemptions for religious practice. No one, Gerson included, has any expectation that registration will exempt Church members from copyright law. "What the registration has done mostly is strengthen our identity," Gerson said. "I think it will be easier to find new members now that we're recognized."

I asked him if he'd seen a boost in converts since the news broke. "I actually haven't checked," he said. "If you want I could do it right now." There was a pause while he logged on to the registry: to join the Missionary Church of Kopimism simply requires filling out an online form, as easy as signing up for a mailing list. "Right now we have a little more than four thousand," he said, with no particular enthusiasm. "We got twelve hundred new members in the last week."

Gerson told me that religious persecution is a 'big concern' for the church's adherents. "We all fear going to court for copyright infringement," he said. This, of course, has been a worry for file-sharers long before it was formalized as a religion. What the Missionary Church of Kopimism has done is almost a reverse of how religious persecution usually works: whereas religions have often turned to protest because they feel persecuted, Gerson and his followers, feeling persecuted, turned to religion, in order to reframe and get attention for their protest. (It may sound silly to speak of file-sharing in terms of persecution, but when you think of the case of Thomas Drake, or of Bradley Manning, it seems a little less silly.) And Kopimism is hardly the only faith to have been inspired or shaped by a particular political cause. The Rastafari movement, for example, is as much an anti-colonial resistance movement as it is a religion.

When Gerson talks about Kopimism as a religion, his tone is good-humored, but he also comes off as disarmingly sincere. Even if this religious-registration business is just a bit of political theatre, there's no doubt that there’s an honestly and deeply held conviction at its core: the free exchange of information as a fundamental right. But is that enough to make it a genuine religion? When I asked Professor Backstrom, he hesitated. "Today you can believe in anything, so I suppose the idea of belief is a minor issue in a Northern European setting," he said. "Belief can be a very wide concept." He admitted, though, that he suspects that Kopimism is primarily an activist prank.

"I don't think it's a joke at all," Gerson told me. "I think that many religions have been ridiculed over the years. I don't think we're the first to experience it." The pirate movement's political arm, the Pirate Party, provides one possible future path for Kopimism. People didn't take the Pirate Party seriously at first, either. Then its membership exceeded that of the Green Party, and then the Liberal Party and the Christian Democrats, and then the Centre Party, and then the Young Pirates Association became the largest youth organization of any Swedish political party, and then several other parties and a number of prominent politicians shifted their stances on piracy in a more pirate-friendly direction, and then the Party spread to forty countries. Now the Pirate Party actually holds two seats in the European Parliament. These are early days for the Missionary Church of Kopimism. Who can say how far its gospel will spread?

Keep Religion Out of Public Life

-

It takes only a small spark to relight a smouldering fire. Such a spark was struck recently in Bideford town hall in north Devon: a few days ago a High Court judge ruled that it was unlawful for local councils to include Christian prayers in their formal meetings.

This was in response to a legal challenge from a former councillor and atheist, Clive Bone, in association with the campaigning National Secular Society. Bone had objected to the intrusion of Christianity into the corridors of power, humble though they might seem in Bideford.

This unimportant ruling was enough to rekindle the embers of Britain's faith wars. Eric Pickles, secretary of state for local government, blustered on the radio about this country's Christian heritage and how illiberal and intolerant this was and how the government would soon be changing it all.

Bishops and archbishops protested, predictably. Baroness Warsi, a Muslim, during a quasi official visit to the Pope, called on British society to resist the rising tide of 'militant secularism' and to fight for faith to have a place in public life. Quoting the Pope's fears regarding 'the increasing marginalisation of religion', she urged us to feel stronger in our religious identities, not least in Christianity.

The prime minister made his usual pro-faith noises. As the crackling of the fire grew louder, the Queen herself spoke out at Lambeth Palace in defence of all faiths, which would have surprised her forebear Henry VIII. She also said - with what anguish one can imagine - that Anglicanism has been commonly underappreciated and occasionally misunderstood.

Not only occasionally, according to Britain's most famous militant secularist, Richard Dawkins, who appeared again on the field of battle, or rather on the Today programme, arguing that most people who think they're Christians are wrong. Of those questioned in his Ipsos Mori poll, 54% said they considered themselves to be Christian but, when asked why, fewer than three in 10 said it was because they believed in the teachings of Christianity.

Rather than personal belief, the reasons of 72% were much more likely to be social, to do with the customs of their tribe - not that the poll used that phrase - surrounding birth, marriage, death and charity. Most hadn't looked at the Bible for a year or more and never prayed outside church at all. Predictably this caused an uproar.

Generations of unbelievers have not found it necessary to trash Christianity aggressively You get the impression, as usual, that Dawkins and the militant secularists all enjoy it hugely, although he himself was infuriated to be wrong-footed on air about the full title of Darwin's The Origin of Species.

All this is nasty and alarming. For generations in this tolerant country people of Christian background who are themselves unbelievers have not usually found it necessary, or polite, to trash Christianity aggressively in the inflammatory way of Dawkins and his supporters. I sense something mean-spirited in the extremes of his attacks, even though I agree with his views: he lacks something important that most people have or at least understand in others; 19th-century phrenologists would have called it the bump of religiosity.

A sense of the numinous, a longing for ceremony, a love of the religious punctuation of the year, a need for a regular time to examine one's conscience, a passion for church music - these are all things that appeal to Anglican unbelievers such as me and to unbelievers of all traditions. That is what lies behind Alain de Botton's grand schemes of cathedrals for the faithless, impossibly rational though they are.

Lord Rees, the astronomer royal, once expressed these feelings particularly well. An unbeliever who nonetheless goes to church, he said in an interview: "I share with religious people a concept of the mystery and wonder of the universe and even more of human life and therefore participate in religious services. Of course those I participate in are, as it were, the 'customs of my tribe' which happens to be the Church of England."

It is my tribe, too, and in many ways I have loved it, fearful of real religious faith though I am. Anglicanism is the tribe from which the highest ideals of modern, secular morality have evolved. So until recently I have been strongly against aggressive secularists in spirit, although I largely share their opinions. But things have changed rapidly. The terms of the conflict are quite different now. It is hardly an exaggeration to speak of faith wars.

It is a mystery to me why so many people in public life keep saying that faith is a good thing and we'd all be better off if we had more of it. That seems to me a very flabby-minded and sentimental assumption, arising from the limp-wristed Anglican tradition in which faith rarely amounted to anything remotely challenging to anyone.

Faith is not necessarily a good thing. Some faiths hold views that are repellent to most people and certainly to the indigenous Christian tribe. More importantly, faith itself is the problem. No one can argue with faith. If God or scripture says gays are wicked, or if someone believes her faith insists on a chador (even if she is mistaken), that is that.

Most faiths in Britain are actively competing for an acknowledged place in the public arena within the Establishment. If Anglicanism is an established part of the state, if this country is technically speaking a theocracy, why in the name of equality should not all other religions have a piece of the action too? That's the urgent but unspoken question. It is hard, however much one might fear the tenets of certain other faiths here, to think of any good reason why not.

That is what we are seeing. The growing number of sharia courts in this country is alarming. Yet the Archbishop of Canterbury has defended them. I can’t help suspecting his reason is that he is so anxious to insist that faith has a place in public life and so aware of the unfairness to other faiths of the status quo, that in logic he cannot help himself. Understandably this enrages the secularists and also the more moderate observers, who are alarmed by the incontrovertible tenets of certain faiths.

That is why, however obtuse and unattractive they may seem, the militant secularists are on the right side in the faith wars. It is why, however reluctantly, the polite and tolerant secularists will have to join them and win the war. There can be no place for faith anywhere at all within the political establishment, no privileged space within the public arena.

An Atheist Manifesto

-

In recent years, we atheists have become more confident and outspoken in articulating and defending our godlessness in the public square. Much has been gained by this. There is now wider awareness of the reasonableness of a naturalist world view, and some of the unjustified deference to religion has been removed, exposing them to much needed critical scrutiny.

Unfortunately, however, in a culture that tends to focus on the widest distinctions, the most extreme positions and the most strident advocates, the "moderate middle" has been sidelined by this debate. There is a perception of unbridgeable polarisation, and a sense that the debates have sunk into a stale impasse, with the same tired old arguments being rehearsed time and again by protagonists who are getting more and more entrenched.

It is time, therefore, for those of us who are tired of the status quo to try to shift the focus of our public discussions of atheism into areas where more progress and genuine dialogue is possible. To achieve this, we need to rethink what atheism stands for and how to present it. The so-called "new atheism" may have put us on the map, but in the public imagination it amounts to little more than a caricature of Richard Dawkins, which is not an accurate representation of the terrain many of us occupy. We now need something else.

This manifesto is an attempt to point towards the next phase of atheism's involvement in public discourse. It is not a list of doctrines that people are asked to sign up to but a set of suggestions to provide a focus for debate and discussion. Nor is it an attempt to accurately describe what all atheists have in common. Rather it is an attempt to prescribe what the best form of atheism should be like.

1 Why we are heathens

It has long been recognised that the term "atheist" has unhelpful connotations. It has too many dark associations and also defines itself negatively, against what it opposes, not what it stands for. "Humanist" is one alternative, but humanists are a subset of atheists who have a formal organisation and set of beliefs many atheists do not share. Whatever the intentions of those who adopt the labels, "rationalist" and "bright" both suffer from sounding too self-satisfied, too confident, implying that others are irrationalists or dim.

If we want an alternative, we should look to other groups who have reclaimed mocking nicknames, such as gays, Methodists and Quakers. We need a name that shows that we do not think too highly of ourselves. This is no trivial point: atheism faces the human condition with honesty, and that requires acknowledging our absurdity, weakness and stupidity, not just our capacity for creativity, intelligence, love and compassion. "Heathen" fulfils this ambition. We are heathens because we have not been saved by God and because in the absence of divine revelation, we are in so many ways deeply unenlightened. The main difference between us and the religious is that we know this to be true of all of us, but they believe it is not true of them.

2 Heathens are naturalists

Heathens are not merely unbelievers: we believe many things too. Most importantly, we believe in naturalism: the natural world is all there is and there is no purposive, conscious agency that created or guides it. This natural world may contain many mysteries and even unseen dimensions, but we have no reason to believe that they are anything like the heavens, spirit worlds and deities that have characterised supernatural religious beliefs over history. Many religious believers deny the "supernatural" label, but unless they are willing to disavow such beliefs as in the reality of a divine person, miracles, resurrections or life after death, they are not naturalists.

3 Our first commitment is to the truth

Although we believe many things about what does and does not exist, these are the conclusions we come to, not the basis of our worldview. That basis is a commitment to see the world as truthfully as we can, using our rational faculties as best we can, based on the best evidence we have. That is where our primary commitment lies, not the conclusions we reach. Hence we are prepared to accept the possibility that we are wrong. It also means that we respect and have much in common with people who come to very different conclusions but have an equal respect for truth, reason and evidence. A heathen has more in common with a sincere, rational, religious truth-seeker than an atheist whose lack of belief is unquestioned, or has become unquestionable.

4 We respect science, not scientism

Heathens place science in high regard, being the most successful means humans have devised to come to a true understanding of the real nature of the world on the basis of reason and evidence. If a belief conflicts with science, then no matter how much we cherish it, science should prevail. That is why the religious beliefs we most oppose are those that defy scientific knowledge, such as young earth creationism.

Nonetheless, this does not make us scientistic. Scientism is the belief that science provides the only means of gaining true knowledge of the world, and that everything has to be understood through the lens of science or not at all. There are scientistic atheists but heathens are not among them. Science is limited in what it can contribute to our understanding of who we are and how we should live because many of the most important facts of human life only emerge at a level of description on which science remains silent. History, for example, may ultimately depend on nothing more than the movements of atoms, but you cannot understand the battle of Hastings by examining interactions of fermions and bosons. Love may depend on nothing more than the physical firing of neurons, but anyone who tries to understand it solely in those terms just does not know what love means.

Science may also make life uncomfortable for us. For example, it may undermine certain beliefs about free will that many atheists have relied on to give dignity and autonomy to our species.

Heathens are therefore properly respectful of science but also mindful of its limits. Science is not our Bible: the last word on everything.

5 We value reason as precious but fragile

Heathens have a commitment to reason that fully acknowledges the limits of reason. Reason is itself a multi-faceted thing that cannot be reduced to pure logic. We use reason whenever we try to form true beliefs on the basis of the clearest thinking, using the best evidence. But reason almost always leaves us short of certain knowledge and very often leaves us with a need to make a judgment in order to come to a conclusion. We also need to accept that human beings are very imperfect users of reason, susceptible to biases, distortions and prejudices that lead even the most intelligent astray. In short, if we understand what reason is and how it works, we have very good reason to doubt those who claim rationality solely for those who accept their worldview and who deny the rationality of those who disagree.

6 We are convinced, not dogmatic

The heathen's modesty about the power of reason and the certainty of her conclusions should not be mistaken for a shoulder-shrugging agnosticism. We have a very high degree of confidence in the truth of our naturalistic worldview. But we do not dogmatically assert it. Being open to being wrong and to changing our minds does not mean we lack conviction that we are right. Strength of belief is not the same as rigidity of dogma.

7 We have no illusions about life as a heathen

Many people do not understand that it is possible to lead a meaningful, happy life as a heathen, but we maintain that it is and can point to any number of atheist philosophers and thinkers who have explained why this is so. But such meaning and contentment does not inevitably follow from becoming a heathen. Ours is a universe without guarantees of redemption or salvation and sometimes people have terrible lives or do terrible things and thrive. On such occasions, we have no consolation. That is the dark side of accepting the truth, and we are prepared to acknowledge it. We are heathens because we value living in the truth. But that does not mean that we pretend that always makes life easy or us happy. If the evidence were to show that religious people are happier and healthier than us, we would not see that as any reason to give up our convictions.

8 We are secularists

We support a state that is neutral as regards people's fundamental worldviews. It is not neutral when it comes to the shared values necessary for people of different conviction to live and thrive together. But it should not give any special privilege to any particular sect or group, or use their creeds as a basis for policy. Politics requires a coming together of people of different fundamental convictions to formulate and justify policy in terms that all understand, on the basis of principles that as many as possible can share.

This secularism does not require that religion is banished from public life or that people may not be open as to how their faiths, or lack of one, motivate their values. As long as the core of the business of state is neutral as regards to comprehensive worldviews, we can be relaxed about expressions of these commitments in society at large. We want to maintain the state's neutrality on fundamental worldviews, not purge religion from society.

9 Heathens can be religious

There are a small minority of forms of religion that are entirely compatible with the heathen position. These are forms of religion that reject the real existence of supernatural entities and divinely authored texts, accept that science trumps dogma, and who see the essential core of religion in its values and practices. We have very little evidence that anything more than a small fraction of actual existent religion is like this, but when it does conform to this description, heathens have no reason to dismiss it as false.

10 Religion is often our friend

We believe in not being tone-deaf to religion and to understand it in the most charitable way possible. So we support religions when they work to promote values we share, including those of social justice and compassion. We are respectful and sympathetic to the religious when they arrive at their different conclusions on the basis of the same commitment to sincere, rational, undogmatic inquiry as us, without in any way denying that we believe them to be false and misguided. We are also sympathetic to religion when its effects are more benign than malign. We appreciate that commitment to truth is but one value and that a commitment to compassion and kindness to others is also of supreme importance. We are not prepared to insist that it is indubitably better to live guided by such values allied with false beliefs than it is to live without such values but also without false belief.

11 We are critical of religion when necessary

Our willingness to accept what is good in religion is balanced by an equally honest commitment to be critical of it when necessary. We object when religion invokes mystery to avoid difficult questions or to obfuscate when clarity is needed. We do not like the way in which "people of faith" tend to huddle together in an unprincipled coalition of self-interest, even when that means liberals getting into bed with homophobes and misogynists. We think it is disingenuous for religious people to talk about the reasonableness of their beliefs and the importance of values and practice, while drawing a veil over their embrace of superstitious beliefs. In these and other areas, we assert the right and need to make civil but acute criticisms.

And although our general stance is not one of hostility towards religion, there are some occasions when this is exactly what is called for. When religions promote prejudice, division or discrimination, suppress truth or stand in the way of medical or social progress, a hostile response is an appropriate, principled one, just as it is when atheists are guilty of the same crimes.

12 This manifesto is less concerned with distinguishing heathens from others than forging links between us and others

Our commitment to independent thought and the provisionality of belief means that few heathens are likely to agree completely with this manifesto. It is therefore almost a precondition of supporting it that you do not entirely support it. At the same time, although very few people of faith can be heathens, many will find themselves in agreement with much of what heathens belief. This is what provides the common ground to make fruitful dialogue possible: we need to accept what we share in order to accept with civility and understanding what we most certainly do not. This is what the heathen manifesto is really about.

Christianity In Crisis

-

Christianity has been destroyed by politics, priests, and get-rich evangelists.

If you go to the second floor of the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., you'll find a small room containing an 18th-century Bible whose pages are full of holes. They are carefully razor-cut empty spaces, so this was not an act of vandalism. It was, rather, a project begun by Thomas Jefferson when he was a mere 27 years old. Painstakingly removing those passages he thought reflected the actual teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, Jefferson literally cut and pasted them into a slimmer, different New Testament, and left behind the remnants (all on display until July 15). What did he edit out? He told us: "We must reduce our volume to the simple evangelists, select, even from them, the very words only of Jesus." He removed what he felt were the 'misconceptions' of Jesus' followers, "expressing unintelligibly for others what they had not understood themselves." And it wasn't hard for him. He described the difference between the real Jesus and the evangelists' embellishments as 'diamonds' in a 'dunghill,' glittering as "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man." Yes, he was calling vast parts of the Bible religious manure.

When we think of Jefferson as the great architect of the separation of church and state, this, perhaps, was what he meant by 'church': the purest, simplest, apolitical Christianity, purged of the agendas of those who had sought to use Jesus to advance their own power decades and centuries after Jesus' death. If Jefferson's greatest political legacy was the Declaration of Independence, this pure, precious moral teaching was his religious legacy. "I am a real Christian," Jefferson insisted against the fundamentalists and clerics of his time. "That is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus."

What were those doctrines? Not the supernatural claims that, fused with politics and power, gave successive generations wars, inquisitions, pogroms, reformations, and counterreformations. Jesus' doctrines were the practical commandments, the truly radical ideas that immediately leap out in the simple stories he told and which he exemplified in everything he did. Not simply love one another, but love your enemy and forgive those who harm you; give up all material wealth; love the ineffable Being behind all things, and know that this Being is actually your truest Father, in whose image you were made. Above all: give up power over others, because power, if it is to be effective, ultimately requires the threat of violence, and violence is incompatible with the total acceptance and love of all other human beings that is at the sacred heart of Jesus' teaching. That's why, in his final apolitical act, Jesus never defended his innocence at trial, never resisted his crucifixion, and even turned to those nailing his hands to the wood on the cross and forgave them, and loved them.

Politicized Faith

Whether or not you believe, as I do, in Jesus' divinity and resurrection - and in the importance of celebrating both on Easter Sunday - Jefferson's point is crucially important. Because it was Jesus' point. What does it matter how strictly you proclaim your belief in various doctrines if you do not live as these doctrines demand? What is politics if not a dangerous temptation toward controlling others rather than reforming oneself? If we return to what Jesus actually asked us to do and to be - rather than the unknowable intricacies of what we believe he was - he actually emerges more powerfully and more purely.

And more intensely relevant to our times. Jefferson's vision of a simpler, purer, apolitical Christianity couldn't be further from the 21st-century American reality. We inhabit a polity now saturated with religion. On one side, the Republican base is made up of evangelical Protestants who believe that religion must consume and influence every aspect of public life. On the other side, the last Democratic primary had candidates profess their faith in public forums, and more recently President Obama appeared at the National Prayer Breakfast, invoking Jesus to defend his plan for universal health care. The crisis of Christianity is perhaps best captured in the new meaning of the word 'secular.' It once meant belief in separating the spheres of faith and politics; it now means, for many, simply atheism. The ability to be faithful in a religious space and reasonable in a political one has atrophied before our eyes.

Organized Religion in Decline

Meanwhile, organized religion itself is in trouble. The Catholic Church's hierarchy lost much of its authority over the American flock with the unilateral prohibition of the pill in 1968 by Pope Paul VI. But in the last decade, whatever shred of moral authority that remained has evaporated. The hierarchy was exposed as enabling, and then covering up, an international conspiracy to abuse and rape countless youths and children. I don't know what greater indictment of a church's authority there can be - except the refusal, even now, of the entire leadership to face their responsibility and resign. Instead, they obsess about others' sex lives, about who is entitled to civil marriage, and about who pays for birth control in health insurance. Inequality, poverty, even the torture institutionalized by the government after 9/11: these issues attract far less of their public attention.

For their part, the mainline Protestant churches, which long promoted religious moderation, have rapidly declined in the past 50 years. Evangelical Protestantism has stepped into the vacuum, but it has serious defects of its own. As New York Times columnist Ross Douthat explores in his unsparing new book, Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics, many suburban evangelicals embrace a gospel of prosperity, which teaches that living a Christian life will make you successful and rich. Others defend a rigid biblical literalism, adamantly wishing away a century and a half of scholarship that has clearly shown that the canonized Gospels were written decades after Jesus' ministry, and are copies of copies of stories told by those with fallible memory. Still others insist that the earth is merely 6,000 years old - something we now know by the light of reason and science is simply untrue. And what group of Americans have pollsters found to be most supportive of torturing terror suspects? Evangelical Christians. Something has gone very wrong. These are impulses born of panic in the face of modernity, and fear before an amorphous 'other.' This version of Christianity could not contrast more strongly with Jesus' constant refrain: "Be not afraid." It would make Jefferson shudder.

It would also, one imagines, baffle Jesus of Nazareth. The issues that Christianity obsesses over today simply do not appear in either Jefferson's or the original New Testament. Jesus never spoke of homosexuality or abortion, and his only remarks on marriage were a condemnation of divorce (now commonplace among American Christians) and forgiveness for adultery. The family? He disowned his parents in public as a teen, and told his followers to abandon theirs if they wanted to follow him. Sex? He was a celibate who, along with his followers, anticipated an imminent End of the World where reproduction was completely irrelevant.

The Crisis of Our Time

All of which is to say something so obvious it is almost taboo: Christianity itself is in crisis. It seems no accident to me that so many Christians now embrace materialist self-help rather than ascetic self-denial - or that most Catholics, even regular churchgoers, have tuned out the hierarchy in embarrassment or disgust. Given this crisis, it is no surprise that the fastest-growing segment of belief among the young is atheism, which has leapt in popularity in the new millennium. Nor is it a shock that so many have turned away from organized Christianity and toward 'spirituality,' co-opting or adapting the practices of meditation or yoga, or wandering as lapsed Catholics in an inquisitive spiritual desert. The thirst for God is still there. How could it not be, when the profoundest human questions - Why does the universe exist rather than nothing? How did humanity come to be on this remote blue speck of a planet? What happens to us after death? - remain as pressing and mysterious as they've always been?

That's why polls show a huge majority of Americans still believing in a Higher Power. But the need for new questioning - of Christian institutions as well as ideas and priorities—is as real as the crisis is deep.

The Jerusalem Syndrome

-

Why Some Religious Tourists Believe They Are the Messiah

Shortly after his 40th birthday, the life of a man we'll call Ronald Hodge took a strange turn. He still looked pretty good for his age. He had a well-paying job and a devoted wife. Or so he thought. Then, one morning, Hodge's wife told him she no longer loved him. She moved out the next day. A few weeks later, he was informed that his company was downsizing and that he would be let go. Not knowing where to turn, Hodge started going to church again.

Even though he'd been raised in an evangelical household, it had been years since Hodge had thought much about God. But now that everything seemed to be falling apart around him, he began attending services every week. Then every day. One night, while lying in bed, he opened the Bible and began reading. He'd been doing this every night since his wife left. And every time he did, he would see the same word staring back at him - the same four syllables that seemed to jump off the page as if they were printed in buzzing neon: Jerusalem. Hodge wasn't a superstitious man, he didn't believe in signs, but the frequency of it certainly felt like ... something. A week later, he was 30,000 feet over the Atlantic on an El Al jet to Israel.

When Hodge arrived in Jerusalem, he told the taxi driver to drop him off at the entrance to the Old City. He walked through the ancient, labyrinthine streets until he found a cheap hostel near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. He had a feeling that this was important. Supposedly built on top of the spot where Jesus Christ was crucified and three days later rose from the dead, the domed cathedral is the holiest site in Christendom. And Hodge knew that whatever called him to the Holy Land was emanating from there.

During his first few days in Jerusalem, Hodge rose early and headed straight to the church to pray. He got so lost in meditation that morning would slip into afternoon, afternoon into evening, until one of the bearded priests tapped him on the shoulder and told him it was time to go home. When he returned to his hostel, he would lie in bed unable to sleep. Thoughts raced through his head. Holy thoughts. That's when Hodge first heard the Voice.

Actually, heard is the wrong word. He felt it, resonating in his chest. It was like his body had become a giant tuning fork or a dowsing rod. Taking a cue from the sign of the cross that Catholics make when they pray, Hodge decided that if the vibrations came from the right side of his chest, it was the Holy Ghost communicating with him. If he felt them farther down, near the base of his sternum, it was the voice of Jesus. And if he felt the voice humming inside his head, it was the Holy Father, God himself, calling.

Soon, the vibrations turned into words, commanding him to fast for 40 days and 40 nights. None of this scared him. If anything, he felt a warm, soothing peace wash over him because he was finally being guided.

Not eating or drinking came easily at first. But after a week or so, the other backpackers at his hostel began to grow concerned. With good reason: Hodge's clothes were dirty and falling off of him. He had begun to emit a pungent, off-putting funk. He was acting erratically, hallucinating and singing the word Jesus over and over in a high-pitched chirp.

"Jesus ... Jesus ... Jesus ..."

Hodge camped out in the hostel's lobby and began introducing himself to one and all as the Messiah. Eventually, the manager of the hostel couldn't take it anymore. He didn't think the American calling himself Jesus was dangerous, but the guy was scaring away customers. Plus, he'd seen this kind of thing before. And he knew there was a man who could help.

Herzog Hospital sits on a steep, sun-baked hill on the outskirts of Jerusalem. Its sprawling grounds are dotted with tall cedars and aromatic olive trees. Five floors below the main level is the office of Pesach Lichtenberg, head of the men's division of psychiatry at Herzog.

Lichtenberg is 52 years old and thin, with glasses and a neatly trimmed beard. Born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, he moved to Israel in 1986 after graduating from Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx and has worked at Herzog more or less ever since. It's here that he has become one of the world's leading experts on the peculiar form of madness that struck Ronald Hodge - a psychiatric phenomenon known as Jerusalem syndrome.

On a bright, late summer morning, Lichtenberg greets me in the chaotic lobby of the hospital, smiling and extending his hand. "You missed it!" he says. "We had a new Chosen One brought into the ward this morning." We go down to Lichtenberg's office; on top of a bookcase is a giant shofar, a curved ram's horn that religious Jews sound on the high holidays. A middle-aged British man under the doctor's care had used it to trumpet the Messiah's - that is to say, his own - coming. Lichtenberg explains that allowing me to meet his latest patient would violate hospital policy, and he can't discuss ongoing cases. He'll talk about past patients as long as I agree to de-identify them, as I did with Hodge. "But," he adds, "that doesn't mean we can't try to find a messiah of our own. In a few days, we'll take a walk around the Old City and maybe we'll find one for you there."

There's a joke in psychiatry: If you talk to God, it's called praying; if God talks to you, you're nuts. In Jerusalem, God seems to be particularly chatty around Easter, Passover, and Christmas - the peak seasons for the syndrome. It affects an estimated 50 to 100 tourists each year, the overwhelming majority of whom are evangelical Christians. Some of these cases simply involve tourists becoming momentarily overwhelmed by the religious history of the Holy City, finding themselves discombobulated after an afternoon at the Wailing Wall or experiencing a tsunami of obsessive thoughts after walking the Stations of the Cross. But more severe cases can lead otherwise normal housewives from Dallas or healthy tool-and-die manufacturers from Toledo to hear the voices of angels or fashion the bedsheets of their hotel rooms into makeshift togas and disappear into the Old City babbling prophecy.

Lichtenberg estimates that, in two decades at Herzog, the number of false prophets and self-appointed redeemers he has treated is in the low three figures. In other words, if and when the true Messiah does return (or show up for the first time, depending on what you believe), Lichtenberg is in an ideal spot to be the guy who greets Him.

"Jerusalem is an insane place," one anthropologist says. "It overwhelms people."

While it's tempting to blame the syndrome on Israel's holiest city, that wouldn't be fair. At least, not completely. "It's just the trigger," says Yoram Bilu, an Israeli psychological anthropologist at the University of Chicago Divinity School. "The majority of people who suffer from Jerusalem syndrome have some psychiatric history before they get here." The syndrome doesn't show up in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but it and its kissing cousins are well-known to clinicians. For example, there's Stendhal syndrome, in which visitors to Florence are overwhelmed by powerful works of art. First described in the early 19th century in Stendhal's Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio, the disorder can lead to spontaneous fainting, confusion, and hallucinations. Paris syndrome, first described in 1986, is characterized by acute delusions in visitors to the City of Light and for some reason seems to preferentially affect Japanese tourists. Place, it seems, can have a profound effect on the mind.

What's actually happening in the brain, though, isn't completely clear. Faith isn't easy to categorize or study. Andrew Newberg, a neuroscientist at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, has conducted several brain-imaging studies of people in moments of extreme devotion. The limbic system, the center for our emotions, begins to show much higher activity, while the frontal lobes, which might ordinarily calm people, start to shut down. "In extreme cases, that can lead to hallucinations, where someone might believe they're seeing the face of God or hearing voices," Newberg says. "Your frontal lobe isn't there to say, 'Hey, this doesn't sound like a good idea.' And the person winds up engaging in behaviors that are not their norm."

The psychosis typical of Jerusalem syndrome develops gradually. At first the victim may begin to feel symptoms of anxiety, nervousness, and insomnia. The next day, there may be a compulsive urge to break away from the rest of the tour group and visit holy places like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Sufferers might follow this with a series of purification rituals such as shaving all of their body hair, clipping their nails, or washing themselves free of earthly impurities. The afflicted may then venture into the Old City to shout confused sermons claiming that redemption is at hand. In some cases, victims believe they are merely a cog in an ineffable process, helping to set the stage for the Messiah's return with some small task they've been given. In more extreme cases, they can be swept up by psychotic delusions so intense, so ornate, that they become convinced they are Jesus Christ. "Jerusalem is an insane place in some ways. It overwhelms people, and it has for centuries," Bilu says. "The city is seductive, and people who are highly suggestible can succumb to this seduction. I'm always envious of people who live in San Diego, where history barely exists."

In other words, what you can blame Jerusalem for is looking like, well, Jerusalem. The Old City is a mosaic of sacred spaces, from the al-Aqsa Mosque to the Western Wall of the Temple Mount to the well-trodden stones on which Jesus supposedly walked. Like every city, it's the combination of architecture and storytelling that makes Jerusalem more than just a crossroads. Great cities, the places that feel significant and important when you walk their streets, always rely on stagecraft - a deftly curving road, finely wrought facades, or a high concentration of light-up signage can all impart a sense of place, of significance. This architectural trickery can even instill a feeling of the sacred. The colonnades around St. Peter's Square at the Vatican, the rock garden at Ryoanji temple in Kyoto, and the pillars at the Jamarat Bridge near Mecca all shoot laser beams of transcendence into the brain of a properly primed visitor. "Part of the experience of going to these places is the interweaving of past and present," says Karla Britton, an architectural historian at the Yale School of Architecture. "There's a collapse of time. And for some people who visit these sacred sights and spaces, this collapse can be psychologically disorienting. The whole act of pilgrimage is deliberately intended as a kind of disorientation."

That in and of itself doesn't make someone crazy. "There are a lot of people who come to Israel and feel God's presence, and there's nothing wrong with that," Lichtenberg says. "That's called, at the very least, a good vacation. God forbid a psychiatrist sticks his nose into something like that." He smiles and rubs his beard. "But the question is, at what point is belief OK and at what point is it not OK? If someone says, 'I believe in God,' OK. And if they say, 'I believe the Messiah will come,' fine. And if they say, 'I believe His coming is imminent,' you think, well, that's a man of real faith. But if they then say, 'And I know who it is! I can name names!' you go, wait a second - hold on!"

When people with Jerusalem syndrome show up at the hospital, doctors often just let them unspool their stories, however strange the narratives may seem. If the people aren't dangerous, they are usually discharged. Violent patients might be medicated and kept under observation pending contact with their family or consulate. After all, the most effective treatment when it comes to Jerusalem syndrome is often pretty simple: Get the person the hell out of Jerusalem. "The syndrome is a brief but intense break with reality that is place-related," Bilu says. "When the person leaves Jerusalem, the symptoms subside."

Lichtenberg didn't know any of this when he started at Herzog. Then, shortly after he began his residency in the late 1980s, he met a 35-year-old Christian woman from Germany. She was single and traveling alone in Israel. He remembers her as being gaunt, prematurely gray, and highly educated. The police had picked her up in the Old City for badgering tourists about the Lord's return. "She arrived in a state of bliss because she believed the Messiah was coming," Lichtenberg says. "I probably thought, she's just meshuggeneh."

Over the next few days, Lichtenberg underwent a transformation of his own. He became obsessed with the German woman's case. He thought about how she would ricochet from periods of giddy rapture to moments of outright hostility and confusion. During her more manic moments, she wanted to share the Good News with the doctor. In her more depressive ones, she wandered the psychiatric ward desperately trying to hear the voices in her head that had gone momentarily silent. She would rub her temples as if she could dial in the voice of God, like someone trying to tune in a far-off radio station.

The woman stayed at the hospital for a month, until the doctor could arrange for her to be sent home. Lichtenberg has no idea what happened to her after she returned to Germany, but more than 20 years later he can still recall the smallest details of her case. "It was so interesting talking to her, but I was also a little embarrassed because there was no one at the hospital to encourage that sort of thing back then. At the time, the thinking here was more like, OK, what dosage is she getting? Should we increase it?"

This way of thinking is more sympathetic than many psychiatrists would call for. Actually, it wasn't that long ago that one respected Israeli physician put two patients who both claimed to be the Messiah in a room together just to see what would happen. Each rabidly accused the other of being an impostor, barking fire-and-brimstone threats.

Self-styled prophets have been journeying to Jerusalem on messianic vision quests for centuries. A certain Nazarene carpenter was merely the most charismatic and most written about. But it wasn't until the 1930s that an Israeli psychiatrist named Heinz Herman clinically described Jerusalem syndrome for the first time. One of his early cases involved an Englishwoman who was so convinced the Second Coming was at hand that she climbed to the top of Jerusalem's Mt. Scopus every morning with a cup of tea to welcome the Lord.

Most cases are harmless, but there have been disturbing exceptions. In 1969 an Australian tourist named Denis Michael Rohan was so overwhelmed by what he believed to be his God-given mission that he set fire to the al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam's most sacred sites, which sits atop the Temple Mount directly above the Wailing Wall. The blaze led to rioting throughout the city. Rohan later said that he had to clear the site of "abominations" so it would be cleansed for the Second Coming. (The mosque was rebuilt by a Saudi construction company owned by Osama bin Laden's father.)

More recently, an American man became so convinced he was Samson that he tried - and failed - to move a block of the Wailing Wall. An American woman came to believe she was the Virgin Mary and went to nearby Bethlehem to search for her baby, Jesus. And a few years ago, the Israeli press reported on a 38-year-old American tourist who, after spending 10 days in Israel, began roaming the surrounding hills muttering about Jesus. Shortly after being hospitalized, he jumped off a 13-foot-high walkway near the emergency room, breaking several ribs and puncturing his lung.

Lichtenberg says that during times of uncertainty and conflict (not infrequent in Israel), admissions to his ward spike. For example, in late 1999, when the rest of the world quaintly panicked about the Y2K bug and whether they'd be able to use their ATMs on January 1, Israel was on high alert, afraid that deranged religious crazies would flock to Jerusalem in anticipation of a millennial apocalypse. At the peak, five patients a week were brought into Lichtenberg's ward. The country's defense forces were concerned that someone would try to blow up the al-Aqsa Mosque, finishing the job Rohan started 30 years earlier.

What The Daily Show Teaches About Religion

-

As difficult as it is to find good writing about religion, it is harder still to find good television about religion. Most televangelists do not do good (challenging, nuanced) religious television: one of their goals may be to educate, or win converts, but they have to raise money, and offering sophisticated portraits of religion is as likely to close people's wallets as open them. Religious television series tend to be unwatchable: no Touched by an Angel for me. And talk-show hosts are rarely any better when it comes to religion. The skepticism of Bill Maher can be as simplistic as the basest prosperity gospel, and we should all be glad that the eager gullibility of Oprah is now quarantined on her own network. Except for public television's Religion and Ethics Newsweekly, it is hard to find intelligent talk about religion on TV.

Except for Jon Stewart, that is. The secular Jewish comedian, host of Comedy Central's The Daily Show, covers religion often, but more important, he covers it well. Stewart seems to genuinely enjoy interviewing religious figures, whether of the left (like Sojourners magazine's Jim Wallis) or the right (like pseudo-historian, political advisor and textbook consultant David Barton). Some of The Daily Show's best sketches deal with religion, and his writers and multi-ethnic cast - including one of the few recognizable Muslim comedians in America, Aasif Mandvi - frequently move beyond satire. They are often funny, but just as often smart.

Above all, however, Stewart and his writers do two things that make them unique on popular television. First, they cover - and yes, I would say "cover," not just satirize or mock - a wide range of religions. If you watched only The Daily Show, you would nonetheless learn, in time, about Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and a whole spectrum of smaller faiths, a category that I would argue includes atheism. And second, they pay attention to points of theology that more traditional news and talk shows skip over. Using chunks of time that would be unthinkable on a network newscast - six minutes for a segment on Mormonism! - The Daily Show teaches the finer points of belief, mining them for humor but at the same time serving a real educational function.

Stewart comes at religion with buckets of derision, but I do not find him offensive, nor should anyone who enjoys comedy. Like so many of the best comedians, he is an equal-opportunity hater. Sometimes it's atheists he cannot stand, as in his bit about the beams in a shape of the cross that survived the Ground Zero wreckage, which the American Atheists did not want displayed. Sometimes it's the Catholic church, which last November proved a useful point of comparison for the football culture at Penn State: "I get that it's probably hard for you to believe that this guy you think is infallible, and this program you think is sacred, could hide such heinous activities, but there is some precedent for that," Stewart said, referring to coach Joe Paterno and the sex-abuse scandal. "Yeah, and just like with the Catholic Church, no one is trying to take away your religion, in this case football. They're just trying to bring some accountability to a pope, and some of his cardinals." In both cases, it was the culture of certainty that Stewart was mocking, not the belief system itself. It was the human tendency toward hubris.

But of course belief systems are fair game, too. In fact, Stewart and his writers have realized that good theology - getting people's beliefs right - happens to make for good humor. Consider a bit that aired last October, in which Stewart interviewed cast members Samantha Bee and Wyatt Cenac on the differences between Mormonism and traditional Christianity. Bee, a fair-complected Canadian, was playing a Mormon, wearing a shirt that said "Team Mormon"; and Cenac, a black man of Haitian ancestry, was wearing a shirt that said "Team Normal." Bee began by complaining about the tee shirts they were made to wear: "Why is Wyatt 'Team Normal'? That implies that Mormons aren't normal ... We are not a cult. Mormonism is a proud religion founded by a great man who was guided by the Angel Moroni to golden plates buried in upstate New York that he placed in the bottom of a hat where he read them using a seer stone."

Matters devolved from there. Team Mormon and Team Normal began arguing about which group is crazier: the one that believes Jesus was born of a virgin and the Holy Ghost, and that he rose from the dead and ascended to Heaven, or the one that believes all that plus the story that he then returned to Missouri. Jon Stewart intercedes, saying that both Bee and Cenac seem happy to suspend disbelief when it comes to the basic tenets of the New Testament. Both Bee and Cenac then take license to turn on Stewart, for being an adherent to a religion in which "it's normal to hang out in someone's living room and watch a guy with a beard cut off a baby's penis while everyone eats pound cake!" (as Bee puts it). The bit is as comedically deft as it is religiously shrewd: how often do we catch ourselves rolling our eyes at someone else's belief system, only to realize at the last second that we believe some crazy things ourselves? In that regard, Stewart is a stand-in for all of us, enjoying some fun at the expense of other religions until the gods of dramatic irony hold a mirror to his face.

And except for the fact that circumcision doesn't involve the whole penis ("In my defense," Stewart says, "it's just the tip, and the cake is incredibly moist"), the dialogue is exceptionally accurate about all three religions: traditional Christianity, Latter-day Saint practices, and Judaism. The Mormons' special underwear is played for laughs, it's true - but the point is that Stewart and his writers convey more specifics about religious practice in less than four minutes than any documentary or nightly-news segment I've ever seen.

And the implicit message is one that religion scholars are always trying to convey: all religions have beliefs that seem bizarre to outsiders, and “cult” is often just a word to describe the other guy’s religion. The Daily Show approaches American religion in the spirit of tolerance, but not with the wimpy, eager-to-please hand-wringing that characterizes so much liberal dialogue in this country. Rather, religions are shown to be strange and possibly cringe-inducing: our job is to take an honest look, then tolerate them anyway. It’s a call to rigorous citizenship.

At some point, every one of Stewart’s regulars is called upon to represent a different religious group — Mandvi is often the Muslim, Cenac the Christian, and in one episode the Englishman John Oliver tries to claim Halifax, Nova Scotia, as a new holy site for Jews (“Challahfax” — although according to Mandvi, who is trying to claim the site for Muslims, it is pronounced “Halalifax”). The cast is like a merry band of religious satirists, with a joke for every faith playing in their repertory.

Stewart himself has said very little about his own Judaism, although he is clearly non-practicing by most any definition: he has gone to work, and recorded shows, on the High Holidays, for example. The writer Marty Kaplan tells the story of moderating a forum about why Jews who don’t believe go to synagogue on the holidays: “At one point, a congregant, without prompting, told the room that Stewart didn’t take the High Holy Days off,” Kaplan writes. “His tone was a mixture of anger and disappointment, the kind of sentiment someone might feel about a misguided family member.” And it so happens that I think Stewart’s humor might even be stronger, more durable, if it weren’t all quite so frivolous to him. For example, the writer Shalom Auslander, who was raised very religiously, is capable of a kind of enduring, deeply poignant satire that is beyond Stewart. Similarly, I suspect that Stephen Colbert, erstwhile Daily Show cast member and now host of The Colbert Report, has comedic hues that come from his Catholic religiosity, which he speaks openly about.

But if Stewart is himself indifferent to religion, he is clearly not bitter about it. There is no apparent ideology, either religious or skeptical, animating Stewart’s treatment of religion. More than anything, he and his writers have the scrupulosity of objective journalists. They win laughs without deforming, or even exaggerating, the religion’s actual beliefs. This is an extraordinary feat. Most religious humor, especially on television or in the movies, depends on stereotypes, which are by definition crude and reductive. Stewart’s writers, by contrast, find humor in the specifics of each faith. They would rather laugh at the finer points of belief than stick pins in some caricature. When they are especially fortunate, they can describe a faith through its antagonists — while making those antagonists look ridiculous. Here I am thinking of a segment from 2010, in which Wyatt Cenac interviewed a Muslim woman whose application to be a foster mother was rejected because she would not allow pork products in her house. He made the foster agency look absurd and bigoted, and he helped explain Muslim dietary practices to the audience.